A Passion for the Patuxent

Mapmaker Dave Linthicum has dedicated 17 years

to mapping Maryland’s River

by Sandra Olivetti Martin with Margaret Tearman

Chesapeake Country’s Skyline Drive — with boats, not cars. That’s how Dave Linthicum sees the Patuxent River, which runs by his front door.

Ask him why, and off his tongue rolls a list of Patuxent River glories.

It’s lovely, for one, he says, with a quiet beauty that creeps up on you like fog.

The Patuxent is historic. Humans have lived on its shores for 10,000 years, leaving their relics and place markers. Native Americans wrote their chapters of history on the land, but Captain John Smith wrote a book on his exploration of the Chesapeake, including the three August days in 1608 his men paddled his shallop 40 miles up the river. Today the Patuxent is one segment of the 3,000-mile Captain John Smith Historic Trail, which makes it not only a memorable pathway but also richly interpreted.

The War of 1812 followed the Patuxent River as far as Upper Marlboro, which the British reached just as the 17-ship U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla burned in the Patuxent near where today you cross the river on Rt. 4. The Americans burned their ships to keep them out of British hands, which did not stop the British from burning Washington three days later. Plenty will be written and said about this chapter of the river’s history with the war’s bicentennial just ahead.

Signs of human habitation are all around. But you have to know where and how to look to see old sunken piers, old roadbeds, graves and underwater remains.

So if you’re into history, this river’s a place to find it.

The Patuxent River takes you to interesting places. You can follow the river to marinas, museums, historic mansions, parks, preserves and visitor centers — all within an easy walk of where you step off the river.

It’s easy to get to. The Patuxent is entirely within Maryland, from its source at Parrs Ridge in Frederick County to its wide mouth at Drum Point on the Chesapeake Bay. At 115 miles long — about the length of Skyline Drive — it offers lots of access points to lots of people. Washington, D.C., is only 19 miles distant.

The Patuxent is doable in lots of ways. You can sail in the wide lower river, even above Benedict at Mile 22, if you can get the drawbridge to open for you. Larger boats can motor at least that far up. Smaller boats, like river-lover John Page Williams’ 16-footer can explore beyond Patuxent River Park at Mile 42 to about Mile 50. Above the Benedict bridge, “The river narrows and meanders another 12 to 15 miles with fairly deep water until it begins to get shallow in the paddlers’ havens of Patuxent River Park, Jug Bay Natural Area and Merkle Wildlife Sanctuary.” You’ll learn those facts and more about your journey at www.patuxentwatertrail.org.

For the Patuxent River now has its own trail.

“ I think it creates both a perfect storm for getting people more engaged in their waterfront and a fulcrum for land preservation efforts,” says Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman of the Patuxent River Water Trail. “Campsites are like potato chips. You can’t have just one. Otherwise you have no place to go. If you have one campsite, you have to have others.”

I think it creates both a perfect storm for getting people more engaged in their waterfront and a fulcrum for land preservation efforts,” says Patuxent Riverkeeper Fred Tutman of the Patuxent River Water Trail. “Campsites are like potato chips. You can’t have just one. Otherwise you have no place to go. If you have one campsite, you have to have others.”

Because of the Patuxent River Trail, amenities support natural beauty and history to make the river more welcoming. There are new campsites on the river and new water trail signs keyed to river miles.

The www.patuxentwatertrail.org website also helps make the river a community. There you’ll find opportunities to get on the river with people of shared interest, learn about its history and ecology and join in its restoration. You’d learn that you could be a Patuxent River Roughneck and help maintain signage and clear paddling snags and blocked fish passage. You’d learn that, instead of reading about the river in Bay Weekly, you could be out on the Patuxent River Sojourn, sharing “five days and four nights of fun, paddling and river bonding.”

The Patuxent River gets you out of your car. “Paddling, fishing and boating; biking, hiking and horseback riding; orienteering and geocaching — not driving,” says Linthicum.

The river also gets you into nature. Nine thousand contiguous acres of open land surround the river from Mile 371⁄2 to Mile 501⁄2. Thus, Linthicum notes, it’s the largest tidal preserve and the fifth largest contiguous public park preserve within 30 miles of either Baltimore or Washington.

All this, yet its potential is unrealized, so it’s fresh and opportune — a place where you can still be an explorer, if not quite the indefatigable John Smith.

Lost without a Map

All that and more is true, Linthicum says. A get-it-done kind of guy, the 54-year-old, former Eagle Scout puts more than talk in his determination to get you on the Patuxent.

A nearly life-long dweller in the realm of mapmaking, Linthicum knows one true fact of American history. Once there was a map, people used it to get there.

“Dave is not like other people,” says partner Peggy Brosnan, whose love of maps focuses on where they can take you. “He can look at a map and see amazing things.”

So that you can get on the Patuxent, mapping the river and its surrounding public land has been Linthicum’s “labor of love” since 1993.

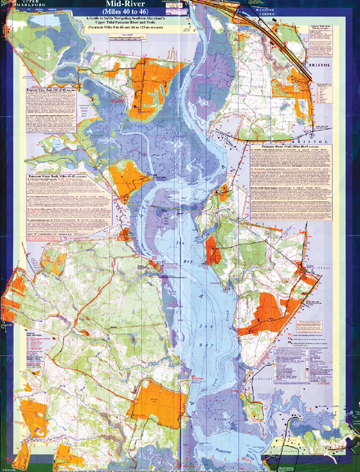

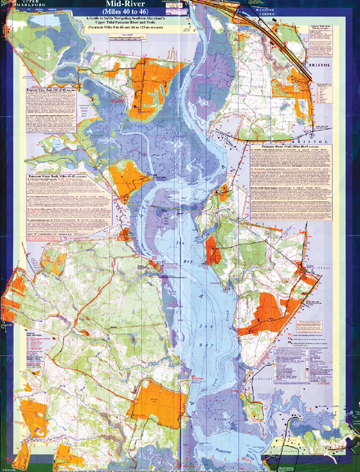

“In 17 years, I’ve paddled and hiked over every inch of this map, sometimes on snowshoes,” he says as he unfolds his waterproof masterpiece on the river’s sandy shore and locates us at Mile 42, right in his own front yard.

The Patuxent River Water Trail Guide & GPS-Ready Map began, like most modern maps, with an aerial photograph from the United States Geological Survey or, more recently Google Earth. Much of modern mapping is done on computer. On those foundations, Linthicum has overlaid experience. “I don’t use a computer when I’m walking. Or GPS,” he says. “By eye and pace counting, I can measure more accurately over short distances. Every second I’m walking, I’m counting paces and doing compass work.”

Those age-old methods have, over the centuries, produced maps of astonishing accuracy.

John Smith’s 1608 maps of the Chesapeake, for example. Smith mapped with very low technology, yet, Linthicum says, “his maps were not exceeded in quality until 1670. We know from his map that he got about as far as what’s now Merkle Wildlife Sanctuary. His measurements were re-examined in 2008, when a shallop built by the Sultana Projects retraced his expedition.

Out on land and water, Linthicum marks his observations on a paper map, Smith style. But Smith didn’t have Linthicum’s aerial photos, nor 17 years.

“Every mark matters,” the cartographer says.

By day at the State Department, Linthicum’s job is boundary delineation. Half his time, he spends studying “100-year-old maps and treaties” so he can correctly draw the borders of countries like Kosovo or Macedonia. War and peace can depend on his precision.

photo courtesy of Cynthia Bravo

|

War, and the need to safeguard our troops, created Linthicum’s job. “At first, American soldiers in Afghanistan were relying on Soviet paper maps because they were more accurate than ours,” he explains. “Of course, they couldn’t read the Cyrillic alphabet. When they went out into the field, it was not safe. We had soldiers shot because they were in the wrong place.”

War, and the need to safeguard our troops, created Linthicum’s job. “At first, American soldiers in Afghanistan were relying on Soviet paper maps because they were more accurate than ours,” he explains. “Of course, they couldn’t read the Cyrillic alphabet. When they went out into the field, it was not safe. We had soldiers shot because they were in the wrong place.”

On the Patuxent, the stakes are not quite so high.

That makes Linthicum no less accurate or detailed in his Patuxent River mapmaking. Other scientists, from Johns Hopkins University, the University of Maryland and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, for example, use his map for their 100-by-100-meter studies of discrete environments.

“They want every little wetland and seep,” Linthicum says, and he has accommodated, with every one marked in symbols on his map, even the vernal pools that, by definition, are short-lived phenomena born of spring rain. Light blue marks the vernal pools on his map.

Dark green areas are ones “you need a machete to get through,” Linthicum says. “White ones, you could drive a buggy through.”

Local knowledge comes from people who live on and use the river and from researchers who share his fascination with the Patuxent and its environs.

But by and large, Linthicum has done all this trekking and mapping on his own, building on skills he learned as a Scout.

He credits Scoutmaster Ray Robley — who died at 85 on April 29 — with guiding him into the land of maps. “After he saw me at 12 poring over a map orientation exercise, not realizing that underneath was another identical map already taped down and oriented correctly, he kept pushing me into mapping,” Linthicum recalls. “He got me in to visit Goddard Space Center to see their cutting-edge work of looking at wetlands and environmental stuff.”

Scouting has also remained part of Linthicum’s life. Among his two dozen or so published recreational or public use maps are many for the Scouts, including a map of Broad Creek Memorial Scout Reservation in Harford County, which, with Linthicum’s help, is mostly protected in perpetuity through a permanent conservation easement with Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

“Paddling and hiking over every inch of this map since 1993 has led to some odd events,” Linthicum says. “Sighting a huge American bison was my oddest.”

Once upon a time, the bison was native to Maryland. Still, Linthicum’s sighting was probably unique in our times. The wooly beast had escaped from a farm and was free for three weeks in the mid-1990s. Lots of other wildlife, however, lives in the river and its surrounding greenway of tens of thousands acres. Bald eagles, blue herons, osprey; beavers, muskrats, river otter and mink; red-bellied turtles and yellow perch.

“It’s not hard to fall in love with this river,” he says of his 17-year affair.

Linthicum’s Picks

Mid-River

Anne Arundel-Calvert-Prince Georges border

Jug Bay (Mile 42) and Patuxent tributaries Mataponi Creek (Mile 41), Lyons Creek (Mile 40), Western Branch (Mile 43) and Charles Branch (Mile 43).

In Patuxent River Park off of Croom Airport Road, rent or put your own boat in at Jackson Landing (Mile 42); put-in at Selby Landing (Mile 41). Here, too, are three Patuxent Water Trail campsites and a rich array of wildlife.

To stretch your legs, paddle up to some riverside trailheads including old growth forest (at Iron Pot Landing campsite), mature bald cypress trees (at the Black Walnut Nature Area boardwalks) or the historic Mt. Calvert mansion/museum/archaeological dig.

White Oak Landing campsite (Mile 39) offers a stroll to a fire tower or to a wooden bridge over Mataponi Creek, all in the middle of 9,000 protected acres.

Down River

Greenwell State Park (Mile 8, on the St. Marys side)

Greenwell State Park’s convenient put-in provides access to a remote paddling campsite (Mile 9) and short walk-up access to the 1703 Sotterley Plantation mansion tours and programs (Mile 9).

For experienced kayakers on a calm day, a couple miles of public shoreline to explore on the Calvert side at Jefferson Patterson Park (Mile 10) may be worth the 1-1⁄2-mile paddle across the Patuxent.

Up River

The upper tidal section from Queen Anne (Mile 52) to Pennsylvania Ave./Rt. 4 (Mile 46), Anne Arundel and Prince George’s counties

Scorching sun and unfavorable winds are rarely a nuisance in this narrow, remote-feeling stretch of the Patuxent (until you near Rt. 4). For an extra challenge, some paddlers start at Governors Bridge (Mile 58) or at the new Anne Arundel Parks ramp at Davidsonville Park (Mile 56). Miles 58 to 52 are non-tidal but flat, with just a few riffles and tree blockages, a lovely area that definitely benefits from moderate or higher water levels most reliably found November through June.

Patuxent River Park (301-627-6074) can help with gate access to the nice floating pier put-ins at Queen Anne-4H and Governors Bridge Natural Area. The old Queen Anne Bridge (Prince George’s side) and Governors Bridge (either side) will work too, if you don’t mind some mud and are not leaving a car overnight. The park or the Patuxent Riverkeeper (301-429-8200) at Queen Anne can assist with rentals and a car shuttle or drop-off.

–Dave Linthicum

|

On the Map

There are maps, and then there are maps. Linthicum’s 22-inch-by-291⁄2-inch, double-sided, full-color map is as much an encyclopedia of Patuxent River lore as it is a guide to safe navigation. Competing for space and for your eye are Linthicum’s comprehensive mile-by-mile notes to what you’ll find on both water and land — plus symbols, scales and grids.

The Patuxent River Trail’s 60 sites, keyed to the map’s mile markers, are annotated by Linthicum with information that is practical, ecological and historical.

At Mile 44, for example, the note that “Steamships powering up from the Bay through Jug Bay to Bristol Landing until the early 1900s were up to 56 feet wide and up to 210 feet long” gives a paddler on the now-quiet river pause to consider it as a one-time important and busy route for commerce.

On the practical side, the mapmaker reminds that the Patuxent is a tidal river, with shallows and launch points that become sucking mud flats during low tides.

“The Bay’s deepest river is also shallow,” he writes. “It is remarkably easy, even in paddle craft, to become grounded or cut off by mud flats particularly in the 10-mile stretch from Spice Creek Mile 35 to Pig Point Mile 44.”

You won’t find exciting whitewater, but sections can present unexpected challenges, especially in the upriver portion, where submerged trees can block the narrowing river, requiring tight maneuvers and some portages. Here the map is generous with good practical directives: go left; limbo under big tree; channel blocked by big tree; can drag over small trees.

Until you learn your way around, it’s as easy to get confused on the map as on the river. Numerical Trail Marker Points, for example, do not match up with river mile markers. Thus, Trail Marker 1, the Williams Street public launch site at the tip of Solomon’s island, is at Mile 1.4.

Red type is used throughout to mark poor and unofficial put-ins. But you’ll learn far more in the small print of each note, including the presence, or absence, of public restrooms and guidance as to when hunting season makes an area unsafe.

Descriptions of each trail marker site include notes on local river conditions, including GPS coordinates and warnings about tidal changes. As a bonus, Linthicum throws in plenty of activities off the water along the trail, including wildlife sanctuaries, public parks, riverside campsites, points of historical interest and even housing developments. The mapmaker’s observations are fun to read and give great incentive to get out on the river to see it all for yourself, up close and personal, as he has.

And so it goes, for over 100 miles.

Don’t get on the river without reading it. You need to know where you are on the map to know where you’re going on the river. It can be overwhelming, so spread it out and get to know it before unfolding it down to seven-by-11-inch sections to guide your journey. It’s waterproof, so it can go with you in the boat.

Even if you have no intention of setting your butt in a boat, Dave Linthicum’s map is one heckuva good read.

Get Your Copy

Get your copy of The Patuxent River Water Trail Guide & GPS-Ready Map at Jug Bay Visitors Center and Patuxent River Park. Or order from Maryland Department of Natural Resources: Look under Trail Guides at www.shopdnr.com.

![]()