One Hundred Years of Fathers Day Lessons

Ten Chesapeake neighbors tell what Dad taught them

We used to believe that father knows best.

The world is not so simple nowadays. The skepticism that belongs to our teen years comes early and stays late in some families. In others, Dad proves himself to be all too human.

But that’s neither here nor there, because Father’s Day we find the best in the men who sired, reared and guided us. On this day we thank our fathers for all they’ve done for us, given us and taught us.

I suspect as we grow older, the ways we see our fathers change, and so do the lessons we most value. To test that hypothesis, we’ve asked people from 10 decades to tell us their father’s most memorable lesson. Was I right? I can tell you we got some surprises, but just what they are you’ll have to read on to discover.

–Sandra Olivetti Martin (who learned from her father, Gene Martin, how to tell a story and how to judge a good date)

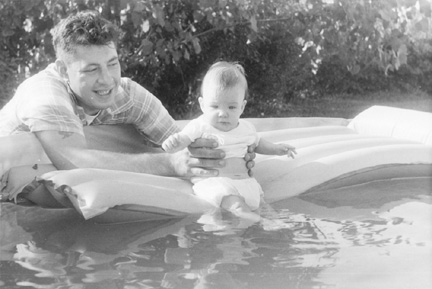

Teaching us a lot about everything.

Teaching us a lot about everything.

Mike Weisburgh, pharmacist, father of 6-year-old Lucy and

3-1/2-year-old Maggie Weisburgh

“Hmmm,” muses six-year-old Lucy, thoughtfully scratching her head. “What does Daddy teach us? That’s a good question. Oh! He teaches us how to ride our bikes so we won’t fall off.”

Her sister, Maggie, bursting with the energy of a three-and-half-year-old, giggles and tells how her daddy “teaches us how to have sleepovers.”

Lucy, being older and wiser, rolls her eyes in exasperation. “That’s silly. We already know how to have sleepovers. But another thing we do is watch the Animal Planet together so we can learn about Mother Earth and life and death. Cuz everything has to die someday.”

Daddy has also taught his girls how to plant flowers — and reminds them to keep them watered.

Don’t forget the importance of hygiene. Always wash your hands.

Both Lucy and Maggie agree that their daddy is teaching them a lot about everything.

Like how not to be afraid of lightning and Ferris wheels.

And how to cook.

“We make good things,” says Lucy.

“Like spaghetti and hot dogs,” adds Maggie.

Why is this lesson important?

“Silly,” says Lucy. “So we won’t be hungry.”

–Margaret Tearman

Help others but take time

Help others but take time

for yourself, too.

Dan Ferro: At-home dad, ice hockey and lacrosse coach, woodworker, father of teenager Finley Ferro

Finley Ferro is one of the busiest people I know. Mornings, she commutes from Annapolis to Towson for classes toward her sports management major or opens at Zu Coffee. Evenings, she closes at Rocco’s Pizza or babysits. At her Bowie Baysox internship, she enters data, delivers fliers and Sumo wrestles in the big suit with patrons between innings. All with a smile.

“I enjoy working and helping others,” says Ferro. “I was the student in class who always volunteered when no one else would. I get it from my dad. He volunteered for everything.

“Growing up, my dad coached me in lacrosse. He always was, and still is, really good at showing you what he wanted done. He taught me how to lead by example instead of tell and then don’t do. When I babysit, I think of what my dad would do. Lately, with two little girls, I’ve been doing a lot of cartwheels.

“But my dad was adamant that I take time for myself too. After half an hour of homework, he’d say, ‘Want a snack? Why don’t you go for a walk?’ It helped me sort my thoughts and stay calm.

“It gives me great pleasure to make someone smile for a little bit of their day. And when I do, I think of my dad for sure.”

–Dotty Holcomb Doherty

A smile and a prayer can carry you through anything.

A smile and a prayer can carry you through anything.

Steve J. Brasington: Navy psychiatrist, father of

20-something Kathleen Brasington, Annapolis pool manager and budding pop star

My father is an achievement-driven man, always striving to do more. At one point in my youth, he held down three jobs: Navy captain, psychiatrist, medical director. Then my parents’ marriage fell apart. His calm confidence carried him through that difficult time, and I hoped he’d learned that we had just wanted him around more. Yet he soon remarried, adopted two teens and returned to active duty.

Seven months into deployment in Iraq this winter, he ran himself ragged and became so ill the Navy had to fly him home directly to the ICU. Scores of antibiotics and one heart surgery later, he’s finally on the mend and realizing for the first time his own limitations. Ever optimistic, though, he’s coping in a typically calm, scientific and faithful fashion: God bless the ingenuity of man, he says.

Dad’s ordeal has taught me that forgetting to stop and smell the roses can kill you, but also that a smile and a prayer can carry you through anything. While he might be many things to many people, he’s first and foremost my dad, and I’m so grateful he’ll be around to do more.

–Jane Elkin

Patience.

Patience.

John Neely Sr., Financial planner, father of 30-something John Neely Jr.

On the field, adrenaline is always pumping, athletes are constantly competing, the risks at stake feel high, and things happen in a blink: not always things on your side. But for John Neely Jr., one thing was always on his side: a father who preached patience.

Growing up, John Neely Sr. always encouraged his children to be patient with people and keep their tempers in check. Among the many lessons John Sr. taught his children, patience was the one that most stuck with his oldest, John Jr. Though it seemed most relevant in his lacrosse days at Severn School and Hampton Sydney College, John has grown to learn a greater depth to the lesson, as he continues to apply it in business and relationships.

“Patience,” John Jr. recalls. “My father always taught me to be patient with people and keep my temper in check.”

–Amy Russell

My father’s toolbox held the

My father’s toolbox held the

secret of friendship.

Gregori Ivanov, father of 40-something Inna Young: City of Annapolis webmaster

My fiancée, Inna Young, is Russian. She is an inspiration to me for many reasons, but mostly because she seems to get along so well with everyone in town and make friends so easily. She knows more about many of my oldest and dearest friends than I do.

I once asked her how she managed to get people to reveal so much about themselves. Here’s what she said:

“I learned from my father Gregori. When I was a young girl growing up in the city of Khabarovsk, we lived in a large high-rise apartment near the Sea of Japan. My father had a wooden carpenter’s toolbox, and after work and on weekends he would go around the building, fixing things for our neighbors. He was very handy, and he loved helping others. He never charged for his services, but he always came back home with a jar of homemade jelly, or a can of caviar, and a story. He knew more about the private lives of the people in our building than anyone else.

“My father wasn’t the kind of person to give advice or preach. But the way he lived each day was an example to me, and I have never forgotten that if you reach out to others — even strangers — and are willing to help them when they need it, even if there is nothing in it for you, you will be rewarded with riches far beyond your wildest expectations.”

–Steve Carr

Life begins one step outside

Life begins one step outside

of your comfort zone.

Alex Koehler, father of 50-something Margaret Tearman, Bay Weekly writer

I was a child when my father began teaching me about the importance of taking chances. Those early lessons came in small bites, literally, at mealtime. Declaring that I don’t like a new, un-tasted food was unacceptable.

“Try it,” my father challenged. “You might like it. If not, what’s the worst that can happen? You don’t eat it again.”

I usually liked what I tasted, and today I enjoy a broad if not sophisticated palate. Any doubt? Check out my rear view.

When I met people who didn’t look like me or who came from different cultures, my father admonished me to “get to know them before you judge them” because “hell, what’s the worst that can happen? You don’t like them.”

Many of those strangers became treasured friends.

Midway through college, I found Mike, and he found a job in Connecticut. When I announced plans to join him, 3,000 miles from home, my father practically whooped with joy. “Good for you. What an adventure,” he said. “Hell, what’s the worst that can happen? You move back.”

I loved Connecticut, but I didn’t love Mike. With my tail tucked between my legs, I returned home.

My father’s only disappointment was that tail tuck.

“You have nothing to be ashamed of. You tried something and it didn’t work out.” But he would have been disappointed had I balked at the unknown.

“If you don’t take any risks, if you never leave your back yard, you might end up an old woman with 15 cats and die wondering what if? Now that would be something to be sorry about.”

Years later, when my career in Los Angeles stalled, I decided to give the East another try. I figured I could find a job in either New York or Washington, D.C. I had been to New York a few times, to D.C. only once. I had a handful of acquaintances in both cities, but little more.

I called my dad, in a quandary about the choice.

“What are you afraid of?” he asked. “Hell, what’s the worst that can happen? You find someplace else.”

When I explained my indecision was not whether to go but which city to choose, it was my dad who, laughing, suggested flipping a coin.

“Can’t lose,” he said. “Heads New York, tails D.C.”

I will never forget the unabashed tears of pride in his eyes when I boarded the plane for Dulles, not just stepping but flying way out of my comfort zone.

Not all of those steps ended in joyful dance. There were plenty of stumbles and a few face-flattening falls.

But no what-ifs.

Six-plus years ago, tired of the long D.C. commute, on a lark I met with the editor of a small, weekly newspaper in Deale. Sandra offered me my first writing assignment: a preview of Edwin McCain’s concert at Calvert Marine Museum.

“I don’t know,” I said to my husband, Tom. “I’ve never written for a newspaper. I don’t have a clue where to start.” And who is Edwin McCain?

Instead of my father — who had died years earlier — it was Tom pushing me to take a chance at a life outside my comfort zone.

“Who knows,” he told me. “You might like it. But you’ll never know if you don’t try.”

And in my head was my dad’s booming voice: Hell, what’s the worst that can happen?

–Margaret Tearman

He was setting all of us up to be a

He was setting all of us up to be a

role model like he was.

Guffrie M. Smith, Sr., father of 60-something Guffrie M. Smith Jr.: Calvert County educator

Because of his humble beginnings, you were in awe of what my father accomplished. His mother died when he was five, and he was raised by his uncle, who worked him from sunup to sundown and hired him out to a dairy farmer. He always said, “Work never killed anyone.” If work killed anyone, it would have been him.

My father didn’t complete school but got his GED in the Army. In World War II, he was wounded in the leg in Italy and got a Purple Heart.

He worked three to four jobs. He was a master barber, ran a trailer park and laundromat, sold wood, plowed gardens and drove a school bus.

He always had a lot of responsibility, and being the oldest of 17, I was given responsibility as jobs were passed down. It was the idea of being a servant. He taught, “Don’t think just of yourself, but what you can do for others.”

I learned to be self sufficient. “Don’t ask anyone to do something you can do for yourself,” he taught. I learned problem-solving, being creative and using whatever was available. He said, “You can do anything you put your mind to.”

In our house we’ve always accepted different types, different races. He taught us, “It doesn’t hurt to be nice to people.”

My father had high expectations for us, that there’s a certain way to act as a Smith. “Put those shoulders up,” he would say. “It’s how you carry yourself.” He was a self-made man, with an air of confidence. I might not have had many clothes, but they were clean and pressed, and my shoes, even if given to me, were shined, and I took pride in it.

He gave me the exposure, opportunity and support to be successful. He was setting all of us up to be a role model like he was. You replicate what you see, and then you pass it on.

–Sandra Lee Anderson

Get your priorities straight. After all we’ve been through, everything else

Get your priorities straight. After all we’ve been through, everything else

is a piece of cake.

Rudolph Heller, father of 70-something Charlie Heller, entrepreneur, writer, teacher

When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, my Jewish father left to fight against them with the British while my Catholic mother protected and hid me. We reunited with my father after the war, and after the Communists took over our homeland, we fled to America.

When foolish decisions in my sophomore year of college caused me to flunk out, I thought my father would blow his stack. Instead he told me, “We beat the Nazis, and we beat the Communists. We’ll get through this together.”

He phoned Oklahoma State University, where I spent my freshman year, and got me readmitted. I graduated from Oklahoma State with the Outstanding Graduate award and stayed on to get my Master’s in engineering.

When my wife Sue gave birth to our son, our baby’s life hung in the balance for several weeks. Again my father told me, “We beat the Nazis, and we beat the Communists. We’ll get through this.” We did, and David grew to become a wonderful son.

After starting and running two entrepreneurial companies for 18 years, I was fired as CEO because of treachery by a member of my management team. My father repeated his advice, and, sure enough, my career took off on a new upward trajectory as head of the entrepreneurship center at the University of Maryland.

My father’s words come back to me each time a crisis occurs in my life or the lives of those I love. I know there is no adversity we cannot get through together.

–Marilyn Recknor

Nothing is given to you — except your family.

William P. Bozman, construction manager for Hecht Co.,

William P. Bozman, construction manager for Hecht Co.,

father of 80-something Bill Bozman

My father was born in 1898 on the Eastern Shore. They were a watering family. He was a middle child of 10 children. Most of the children pursued a life on the water. They were the drudgers and watermen in Champ, Maryland, on the Manokin River.

His father, my grandfather, was a seaman in the 1800s, and the captain of the SS Somerset, a state patrol boat during the oyster wars.

My father never wanted to pursue the water. He loved the water but didn’t want to do that to make a living. So he went to Baltimore, became a carpenter and later went to Washington, where he built the first Hecht store.

When I came out of the army, my father introduced me to construction. We worked together, and I went to work for the Hecht Company.

My father had many attributes I admire. With little education, he overcame handicaps by applying himself. He became very competent, and he proved to me that if I followed his line of thought, I could be okay. He could accomplish anything.

He and my mother were together through my life, and he instilled family values that I try to pass on to my sons: work ethic, honesty, charitable, helping people and recognizing that you can only get what you work for. Nothing is given to you.

–Sandra Lee Anderson

The voice of the opposition.

E.B. Smith Sr., father of 90-something E.B. Smith Jr., retired University of Maryland professor of history

Elbert Benjamin Smith Jr. was eight years old when he became aware of a basic truth about Elbert Benjamin Smith Sr.

“I found out that my father was a Republican. I announced that I was a Democrat,” E.B. Smith Jr. recalls.

There are many lessons his father tried to teach. But, says Smith, what he mostly took from his father was what not to do.

“Every lesson he taught me, I went in the opposite direction. I lived in a constant state of rebellion,” recalls Smith, who is also an author and globetrotting lecturer.

Rural Tennessee in the 1920s and ’30s was about as far from enlightenment about race and religion as you could get. His father, Smith recalls, reflected that racism even though he offered decency to the blacks and the handful of Jewish families in town.

Young E.B.? As a boy he grew up tight with the town’s African Americans, who helped him comb the mountainside to retrieve prodigal cows. His father, whom Smith recalls as “anti-Semitic as hell,” surely maintained raised eyebrows at his son’s choice of a best friend and the best man at his wedding: Isadore Stern.

His father, an entrepreneur, operated the biggest filling station in town and later owned a fleet of buses. But business was far from young E.B.’s calling.

It was the era of the Great Depression, when people needed a helping hand. But except for the Tennessee Valley Authority just down the road, a bonanza for locals, the senior E.B. pointedly rejected the tonics that Franklin Roosevelt administered across the land.

“I recognized such inconsistencies, and I avoided them,” Smith said.

When it was time to go off to college, his father inquired about young E.B.’s choice of studies.

“Sociology and history,” the young Smith announced.

“Son,” his father replied, “that stuff will never make you a dime.”

Perhaps accidentally, young E.B. learned a thing or two from his father, like how to play the stock market. His father also imparted his love for the water. When his son arrived in Maryland in 1968 to teach, he bought two Bay-front homes in a matter of days, purchases he and his family have never regretted.

“He was shrewd. He was tough. And he never gave up,” traits that E.B. Jr., grudgingly, did not reject.

–Sandra Olivetti Martin

Extra Credit

Lessons learned from a father, an uncle and a friend’s father

Ignorance is never bliss.

My father George Beechener

My mother and father thought that the worst thing in the world was to have a child who referred to genitals as pee-pees and who-whos. So they taught me only anatomically correct terms for my body. My father took this one step further by giving me the sex talk when I was six. He didn’t do anything by halves, so this talk included textbook terms and illustrations as well as describing a host of related acts.

What could I do with this wondrous information but share it? So I told my class. My entire first grade class.

As the calls started coming in that night, my mother was horrified. She turned bright red and handed the phone to my father.

“My daughter said what?” I could hear hysterical noises as the parent explained yet again.

“She told your kid everything?”

My father looked at me and furrowed his brow. “Well, was she right?”

A high-pitched noise emitted from the phone.

“Lady, was she right?”

A murmur.

“That’s my girl!” My dad said as he ruffled my hair and hung up the phone.

–Diana Beechener

Plunge into the world around you.

Plunge into the world around you.

My Uncle George

My father taught me about streetcars (okay, he drove them). And how to make chili for Saturday night dinner, how to prune a rose bush, how to wash a car, how to drive and park a car (required then for a driver’s license), how to focus a camera, how to avoid embarrassing situations. Useful advice all.

But it was my Uncle George who taught me everything else. By that I mean the abundant beauty of the natural world in and around Washington, D.C.

The tributaries of the Chesapeake were his haunt and ours. Hiking along the Potomac shoreline looking for lures and observing catfish anglers on the canal. Catching the herring run in early spring on streams near Fort Washington. Pulling a seine net for grass shrimp in the Bay. Celebrating a catch of eels to be salted for crab bait. Exercising patience while waiting for a crab to take that bait from a hand line. Stoking the wood fire to steam the season’s first crab haul. Standing on a pier in Glebe Creek on the South River, body bent in half, shivering, arms and hands pointed to a watery surface that reflected our own image, first steps in learning to dive. That first plunge took trust; Uncle George made it possible. He didn’t have his own kids; he had us, my cousins and me, and we were the richer for it.

–M.L. Faunce

With enough patience and a beer or two, just about any problem can be solved.

My childhood friend’s father Bill Lenck

I was 18 and driving to my friend’s house when my car began making a noise like someone was shooting a machine gun from underneath it. I asked my friend’s dad if he could diagnose the problem.

He listened, then looked underneath the car and said, “Let’s have a beer.”

That wasn’t the answer I wanted, but since I have the mechanical ability of a bovine, I had a beer with him.

Once finished, he took tin snips and cut off both ends of each beer can. He then slid one can into the other and cut them lengthwise.

“We had to wait for the car to cool down,” he explained, as he eased himself under my vehicle. He told me that the pipe to my muffler had rusted and broke in half. He took the two beer cans, wrapped them around the two ends of the broken pipe, thus making a sleeve, and held them in place with two hose clamps The noise was silenced.

The lesson I learned 32 years ago from my friend’s father was that with enough patience and a beer or two, just about any problem can be solved.

–Allen Delaney

![]()

Teaching us a lot about everything.

Teaching us a lot about everything.  Help others but take time

Help others but take time A smile and a prayer can carry you through anything.

A smile and a prayer can carry you through anything.  Patience.

Patience.  My father’s toolbox held the

My father’s toolbox held the Life begins one step outside

Life begins one step outside He was setting all of us up to be a

He was setting all of us up to be a

Plunge into the world around you.

Plunge into the world around you.