by Carrie Steele

Sharing the Bay celebrity of crabs, oysters and Bay grasses is the diamondback terrapin, the newest poster child for Bay restoration.

We’ve all seen a blue crab, and an oyster — though scarce — is no mystery. But terrapins have kept a low profile, hiding out in marshy areas and quietly surviving in Bay shallows and tributaries.

Now these secretive reptiles are basking in the spotlight of environmental restoration projects, and with the help of local conservationists, terrapins have risen to notoriety as an up-and-coming Bay spokes-species.

Out of the Marsh and into the Soup

Out of the Marsh and into the Soup

Malaclemys terrapin, or diamondbacks, have for eons resided in brackish marshes and tidal creeks from Cape Cod down the East Coast, around the Florida Keys and across the Gulf Coast to western Texas. As the only turtle in the world to inhabit solely brackish waters, diamondbacks are perfectly at home in the shallows of the Chesapeake Bay estuary and its tidal waters.

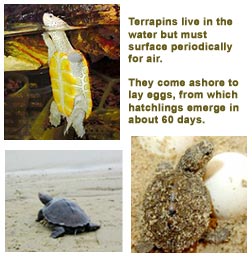

They hibernate in the mud during winter and emerge in late May to mate and lay eggs on sandy summer shores.

Unlike sea turtles, who maneuver through deeper waters with fins, terrapins prefer the shallow inlets along the coast and use their webbed feet to both swim and climb on logs for basking. These water-loving creatures leave their element only for soaking in the sun or for nesting. They build nests to hold their pinkish-white eggs above the high tideline on sandy shorelines. Both nests and hatchlings are vulnerable on the beach.

There, terrapins are prey — especially in their juvenile stage — to crabs, crows, gulls, rats, muskrats, foxes, raccoons and skunks. Terrapins are also predator, for these carnivores feed on aquatic snails, crabs, insects, fish and small bivalves

To help them tear their fishy meals, the turtles have beak-like mouths and long claws. Between claws and shell, their speckled salt-and-pepper skin bears marks as unique to each turtle as a fingerprint to a human. Tan-brown to gray-black shells bearing their namesake diamond pattern on plates called scutes grow in concentric rings, forming a tough exterior.

Their toughness makes mature terrapins a dish you’d have to work at getting. So terrapins’ most troublesome predator is humans.

Terrapin soup isn’t as popular as it used to be, but terrapins have long been trapped by watermen and sold for food. To catch a terrapin you need a permit, and you can trap them legally only August through April, when there is no upper limit on how many terrapins you can take. However, a caught terrapin’s underside shell, or plastron, must be at least six inches long. If you’ve got a keeper, it’s likely a mature female, since the males are generally smaller. Watermen hoist the turtles aboard from fishing nets.

Even today, terrapin supporters worry that taking too many females could create problems for turtle populations.

Bob Evans, a longtime Southern Anne Arundel waterman who was involved with the state terrapin program and who now lobbies for the Maryland Watermen’s Association, used to catch terrapins to sell. He has since focused on fish and crabs. “People don’t catch many terrapins commercially anymore,” he says.

Accidental catches are down, too, since the 1999 law that required turtle excluder devices for crab pots to help prevent accidental turtle fatalities. Turtles can only survive a few hours completely underwater, so keeping them out of crab pots helps terrapins and makes more room for crabs. Evans helped design the Bay version of the excluders, known as TEDs, which are used worldwide to prevent accidental catches of turtles of all sorts.

Accidental catches are down, too, since the 1999 law that required turtle excluder devices for crab pots to help prevent accidental turtle fatalities. Turtles can only survive a few hours completely underwater, so keeping them out of crab pots helps terrapins and makes more room for crabs. Evans helped design the Bay version of the excluders, known as TEDs, which are used worldwide to prevent accidental catches of turtles of all sorts.

These turtle excluders are a thick wire bent into a rectangle strip and secured with hog rings at the narrow end of the crab pot’s funnel. Only four inches long and an inch and a half high, this metal rectangle is too small for the convex-shell of turtles. But thinner crabs easily can scuttle through.

“We used to find them in our crab pots, and then we’d release them,” said Kenneth Keen, a former waterman now at DNR. “Once they started putting in TEDs, that helped a lot.”

Terrapin eggs are also protected by law from harvesting or tampering.

Nowadays when terrapins appear on the market, turtle supporters often buy them to return them to the wild. An adult terrapin usually sells for about $6, says Marguerite Whilden, co-founder of The Terrapin Institute, who reports that she bought the same terrapin three times. “I could tell by the small notch left on the turtle where our tag had fallen out,” she said.

The Terrapin Institute wants the turtles to be common Bay citizens once again. But right now, neither they nor anybody else knows just how many terrapins are out there.

“We don’t have a lot of good, quantified data,” said fisheries biologist Martin Gary at the Department of Natural Resources. Lacking a terrapin management program, the best sources of information DNR has are nesting data it’s collected, University of Maryland studies and estimates made along the Patuxent River in documenting the Chalk Point oil spill of 2001.

Anecdotal evidence points to terrapin survival as well. “Field biologists give feedback throughout the Bay that indicates that terrapins are fairly routinely encountered,” says Gary.

Hoping to find answers to many terrapin questions, researchers have begun tagging female terrapins with small metal bands bearing an identification number in order to get an idea of how many terrapins are out there and where these terrapins go.

Restoration’s New Poster Critter

Terrapins have found their place in the spotlight as the ideal symbol of the Chesapeake — a segue between water and land, since they live mostly in the water but breathe air and come ashore for basking and nesting.

University of Maryland’s athletic teams took the terrapin as their mascot in 1933, and Testudo has since become famous. In 2002, when the University of Maryland’s men’s basketball Terps won the NCAA championship, the school’s athletic department donated part of the proceeds of their Fear the Turtle merchandise to diamondback research and conservation.

Terrapins have found sanctuary under the law as well as fame in sport. In 1994, diamondback terrapins were named Maryland’s state reptile. In April 2001, former Gov. Parris Glendening sparked the Terrapin Task Force, bringing a diverse group of people together to evaluate how terrapins were doing in the Bay. The Task Force later urged that terrapins were “a historically notable species in decline and in need of increased state protections.”

Public awareness of terrapins is widely credited to Whilden’s terrapin outreach program at DNR from 1998 to 2003.

Public awareness of terrapins is widely credited to Whilden’s terrapin outreach program at DNR from 1998 to 2003.

“The terrapin program has greatly increased awareness of terrapins and of environmental awareness,” said Willem Roosenburg, an Ohio University biologist who studies terrapins on the Patuxent River.

Whilden’s terrapin program not only taught students and adults about terrapins but also used terrapins to give a friendly face to conservation and to involve people in stewardship.

But under a new governor the program fell to budget cuts, and the task force ended with the program.

“When we were eliminated from DNR, the problem wasn’t eliminated,” says Whilden, who shifted her terrapin efforts to the private sector with The Terrapin Institute.

Regardless of their sponsor, terrapins work magic when people see them.

“They’re engaging,” says Whilden of these charismatic creatures. “They’re something the public can handle and relate to.”

Terrapins bring shells-full of stories to their spotlight.

The annual hatching of Terrapins coincides with the blooming of Maryland’s native plant, turtlehead, in August.

Terrapins’ history with humans dates back to early Native Americans, who ate their flesh and crafted the shells into tools, weapons, jewelry and more. The very word terrapin is derived from a Native American language. Colonists used terrapins to feed pigs and indentured servants. Terrapins eventually ended up in gourmet bowls of terrapin stew.

Terrapins are no longer common fare for restaurants. But until five years ago, the historic Baltimore restaurant Haussner’s, which has since closed, served terrapin. Culinary adventurers can find recipes in Maryland cookbooks and on the Internet, where you can even find a recipe for low-carb terrapin soup.

Terrapins make storytellers as well as stew. The 13 scutes, or diamond-shaped plates, on the terrapins’ shells make convenient references to history: America’s 13 original states; a Native American tale cites 13 moons on a turtle’s back; 13 years of prohibition (during which terrapin populations strengthened, attributed to the lack of sherry wine for terrapin soup); the 13th amendment abolishing slavery (which ties to the turtle’s days as food for indentured servants).

Another terrapin tale is the terrapin’s success. At a time when oysters battle diseases and overharvesting, Bay grasses can’t seem to plant roots and Bernie Fowler still can’t see his sneakers, the terrapin is one of the few hearty survivors in the Chesapeake. There are no real disease issues, and their population has rebounded after nearly being wiped out from overharvesting in the early 1900s.

With so much negative news about the Bay in the last decade, the terrapin gives the public a reason for hope — which the terrapins unknowingly symbolize by returning to the beach to nest.

Terrapin Trouble

But not all the stories are good ones. Anecdotal research — stories people tell rather than scientific data — shows the decline of the Bay’s terrapins over the last 50 years.

Decreases in the Bay’s abundance have been noticed by watermen and citizens alike.

“As far as I’m concerned, there’s not as many terrapins as there used to be,” says Evans. “Back in the early 1970s on the Patuxent, when we’d haul in the seine net looking for fish, we caught them by the thousands.”

Whilden, too, tells stories of times “when terrapins were commonplace.” As a child, she remembers seeing the heads of swimming terrapins in Whitehall Bay.

Whilden, too, tells stories of times “when terrapins were commonplace.” As a child, she remembers seeing the heads of swimming terrapins in Whitehall Bay.

Roosenburg says that on the Patuxent River, where he conducts most of his terrapin research, “populations are less than 50 percent of what they were four years ago.”

But it’s all comparative, say some.

DNR’s fisheries biologist Gary reports that terrapins appear to be doing well considering the habitat loss and water quality problems of the Bay, especially when compared to other animals that haven’t fared well, such as shad. Even though there was a fishing moratorium on shad in 1980, it didn’t help the population rebound like the success of the rockfish.

“The outlook for terrapins is brighter now than it has been for a while,” says Gary, “They’re more common than people think.”

Like shad, rockfish, crabs, oysters and all the other Bay creatures, terrapins are threatened by pollution, habitat loss and overharvesting.

What’s the number-one threat to the tough-shelled terrapin?

“Over-fishing is a good possibility,” said Mary Hollinger, an aquatic biologist and oceanographer at NOAA as well as a partner in The Terrapin Institute. Because harvesters only take the reproductive females, every time a female is caught, that means thousands fewer eggs will be laid.

Evans has another idea. “Because boat traffic is so severe, the main problem is boat injuries,” the waterman says. Turtles lucky enough to survive contact with a boat propeller may still suffer disease-prone gashes in their shells.

Other problems are the proliferation of water-clouding jet skis, abandoned underwater crab pots and fyke nets — tubelike nets staked in the shallows to catch terrapins but also used for finfish.

But habitat loss likely outweighs all these other factors.

The toughest problem is “having appropriate habitat where they can lay their eggs,” according to DNR’s Gary.

Returning shorelines to habitats that welcome terrapins is on the minds of both DNR and communities.

“We need to make changes in habitat and water quality,” says Stephen Barry, coordinator of Arlington Echo Outdoor Education Center, where a restored natural shoreline has made a good home to terrapins released there in June.

Easing Terrapin Troubles

“We don’t have a dedicated program for terrapin preservation right now,” said DNR’s Gary, who says that the department continues to try to coordinate with Whilden to address crab pot issues and include terrapins in fisheries discussions.

Terrapin preservation may be a by-product of other preservation and conservation efforts, but improving underwater grasses proliferation and oyster restoration are both tied into water quality and habitat that benefits terrapins, says Gary. Terrapins will benefit from ecosystem-based management, which Gary says, is “very much the focus of where fisheries management is going.”

Still, terrapin lovers call for a more drastic step.

“This is not brain surgery,” says Whilden. “Let’s not wait until the next crisis before we look at management.”

NOAA biologist Hollinger agrees. “We need to get a handle on the situation,” she says. “We need a moratorium until we really get a feel for what’s going on.”

An ideal step right now? “A moratorium on terrapin harvesting, with compensation to the fishermen at twice what they would have made on the turtles’ sale,” says Whilden. “And we need to compensate the buyer, too.”

Researchers credit watermen with providing much of the needed data on harvested terrapin numbers. But they worry that what we think we know is nowhere near accurate.

“We know there’s been over 1,500 turtles captured this year, with only 600 reported as being caught for sale. A pet trader told us he bought at least 500,” said Hollinger. “And these are just the ones we know about. Who knows how many others were captured and not reported?”

A Little Help from Their Friends

A Little Help from Their Friends

With their curious eyes, cute faces and easy-to-hold shells, terrapins may be the new face of Bay restoration. It sometimes may be hard to get students to care about a plant or a shellfish that looks like a rock, but there’s something special about a turtle.

That’s why The Terrapin Institute and other groups are turning terrapins into teachers. Terrapins raised in the classroom can provide many lessons about wildlife, history, society and environment, as well as about health and even art. Terrapins have even been brought into classrooms with autistic or disabled children for supervised visits, because often, these children respond well to animals.

Permits allowed the Terrapin Institute 100 eggs for research. They collected the pastel eggs about the size of grapes from Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center, formerly Horsehead Wetlands Center, and various citizen-reported locations.

The eggs, carefully positioned in Pearlite to hold moisture, are kept under close observation at Arlington Echo. There too, hatchlings salvaged from a Holiday Inn parking lot in Grasonville are growing strong in large outdoor tanks protected from predators by wire mesh and observed and fed daily. Next, they’ll move into Arlington Echo’s Resource Lab or head off to Head Start programs to be raised until they’re ready for release. The terrapins are generally low care, have plenty to teach and will grow before students’ eyes in the classroom.

Lots of students and their parents are getting to know baby terrapins nowadays. This spring, home-schoolers released terrapins that they had raised and cared for at Carrie Weedon Science Center in Galesville. Students named the terrapins, the size of a quarter when they arrived at the Center, Hope, Freedom and Braveheart, in honor of their birthday, September 11, 2003. The three were released into their new home at Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center in Grasonville.

“I think the kids became aware that there are terrapins in the Bay,” said Sharon Solberg, teacher at the Science Center, and that they’re “more than just a mascot for the university.”

School groups and recently Planet Earth Campers at Arlington Echo have also set terrapins free onto the natural shoreline.

Not just kids are into terrapins. At Franklin Manor, in Churchton, six tagged female diamondback terrapins were released by the boat ramp on Deep Cove Creek. Community member Pat Keeler helped coordinate the release at the community’s shoreline.

“After Isabel’s destruction, it felt good to be a part of something constructive,” Keeler told Bay Weekly. As far as she knew, none of the tagged terrapins had reappeared, but Keeler’s community looks forward to being a part of the program again.

“After Isabel’s destruction, it felt good to be a part of something constructive,” Keeler told Bay Weekly. As far as she knew, none of the tagged terrapins had reappeared, but Keeler’s community looks forward to being a part of the program again.

Three couples from D.C., enamored with Whilden’s terrapins, asked to raise the hatchlings. Raising terrapins, or protecting hatchlings until they’re less likely to be targeted by birds and mammals, are other ways individuals can help restoration efforts from their homes.

Even businesses want their terrapins — and not for soup. At Herrington Harbour Marina Resort in Rose Haven, terrapins are fostered and lovingly visited by customers and then let go when they grow bigger. Staff and volunteers just released 11 of the turtles in June, and if they acquire more hatchlings, they plan to raise them as well.

Cantler’s Riverside Inn in Annapolis keeps terrapins, as well as horseshoe crabs, in tanks where customers can observe a live terrapin up close while they wait for their food. They have about 10 terrapins that they’ve either caught or received from customers who know of the terrapin tanks. Instead of serving them, this restaurant releases them as they mature.

“Putting something back into the ecosystem is huge from a conservation standpoint,” said Whilden.

More than 1,000 such terrapins have been tagged and released into the Bay since March, according to Hollinger. Many of the terrapins don’t survive in the wild, but many do. Those hearty turtles often can be sighted close to where they were released

According to Whilden, it’s not enough to simply tell students that the Bay is in trouble. Truly educating the public means teaching kids what citizens can do to help — whether it’s writing to their representatives, running for office, organizing themselves to collectively speak out on environmental concerns or physically putting something, like terrapins, back into the Bay — instead of stewing in frustration.

“Kids care when something engages them. There has to be emotion to learning,” said Barry, whose center is raising about 65 of the hatchlings and more than 100 eggs to be raised later in classrooms.

Such restoration projects like releasing terrapins and building habitats help kids to learn how to give back to the Bay.

Turtles are the tool, says Whilden. “Our product is stewardship.”

Perhaps like its cousin the tortoise, the terrapin reminds us that slow and steady wins the race.

Turned Around by a Turtle

“We are running out of time,” Whilden said, slapping her palm for emphasis. Campaigns like hers seize the time, not waiting for years of studies, years that could hurt a population in the meantime.

Science data can tell us where the problems lie, but, says Whilden, “The real trick is how to get society to start doing something about it.”

As we wait, focusing on a small part of the ecosystem, the diamondback terrapin seems to work at bringing attention to the larger issues at stake — taking care of the entire Bay in all its economic, social and environmental realms.

Homing in on one small aspect of the Bay makes conservation more manageable — instead of trying to take on the whole Bay at once. “Instead, we have one product,” says Whilden. “We don’t want to become General Foods.”

In focusing so intensely on terrapins, researchers hope to find ways for everyone to make behavioral changes that will lead to a cleaner and healthier Chesapeake Bay.

“If you ask people if they care about the environment, a great majority will say yes,” said Barry. But Barry would add that the majority of people have no idea how to help the environment, or even understand how their own actions impact the Bay.

“If you ask people if they care about the environment, a great majority will say yes,” said Barry. But Barry would add that the majority of people have no idea how to help the environment, or even understand how their own actions impact the Bay.

A growing number of area residents, however, are becoming concerned about the terrapin.

“Just yesterday someone called in that had a terrapin nesting in their back yard,” said Gary. “I could tell that he was really concerned. Fifteen years ago he wouldn’t have cared.”

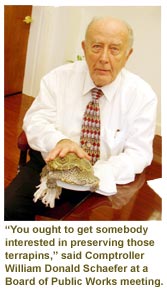

Terrapins even got the attention of Comptroller William Donald Schaefer. Speaking at the Board of Public Works meeting in April, Schaefer chastised the Department of Natural Resources for not supporting The Terrapin Institute’s turtle conservation and research. “You ought to try and get somebody interested in preserving those terrapins,” he said last August.

Now in the glow of public attention, the terrapins continue to prefer to hide out in creeks and shorelines. They’re relatively shy creatures for such intense limelight.

If you spot a tagged terrapin, report the location and tag number to the Terrapin Institute: 410-827-8055. You can even have a terrapin tagged and released in your name with a $5 donation sent to: The Terrapin Institute, P.O. Box 501, Grasonville, MD 21638.

to the top