What will happen to the monthly 333 Coffeehouse after its host and guiding spirit passes the mike into new hands on March 19?

For a dozen years, people have flocked to the Unitarian Universalist Church of Annapolis to what musician Debby McClatchy calls “one of the best of an old breed, the type of venue found back in the days of the folk boom of the ’50s, where not only is the audience treated to nationally known performers, but local musicians, poets and dancers are also given the chance to share their talents, like the old hootenannies.”

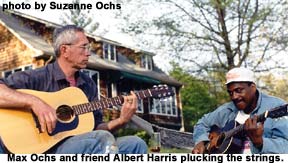

Max Ochs booked the acts, hosted the show and led the crew of other volunteers.

“It’s certainly got his spirit all over it,” says Christina Muir, a musician transplanted from Connecticut who found “a warm, loving, quick entry into the area” by playing at the coffeehouse.

“It’s an unusual format: at least two headline acts, each playing for only 30 to 40 minutes, and the cameos playing two or three songs. He’s really in favor of letting everyone shine, and that has to do with its success: that great family, everyone-gets-to-take-their-turn feeling.”

Ed Sparks agrees. After he’d attended and played at the 333, he and two friends started the Red Door Coffeehouse, which ran for nearly 10 years. “What Max liked to do was not put himself forward. He’d be up there for a few minutes at the beginning, playing and reading poems. But he wouldn’t get up there and hog the spotlight. He’d be so excited about the people he was bringing on.”

They modeled the Red Door after the 333, and sometimes Max played in their shows or they in his. “Someone we ‘stole’ from Max was Janet Hoyt. She came to our shows, too.” An octogenarian poet whose hats were as colorful as her style, Hoyt read at the 333 regularly throughout the last seven years of her life.

“Max always tried to bring the spotlight on people other than himself, he’s very good at promoting his interest in other people,” says musician Neil Harpe, who’s known Ochs for decades.

Max Ochs is that way both onstage and off.

Practicing What He Preaches

“I work in a place whose mission is nearly congruent with my own,” Ochs says. “The mission of the Community Action Partnership as I see it is to improve conditions for the population whose income goes from the federal definition of poverty up to 60 percent of median.

He works full time as public affairs director there, where he’s spent 15 of the past 30 years in different roles. This one includes hosting a weekly show on local radio station WRYR, 97.5FM, combining music, poetry and community issues with information about the agency’s programs (Thursdays from 4 to 6pm).

His volunteer work includes mentoring, teaching citizenship classes, playing music and being an activist. “And every time you turn around, he’s doing some really nice thing for a neighbor,” says his wife, Suzanne.

He also teaches continuing education classes on conflict resolution at Anne Arundel Community College, continuing work he did as co-executive director of the Anne Arundel Conflict Resolution Center from 1995 to 1998.

He also teaches continuing education classes on conflict resolution at Anne Arundel Community College, continuing work he did as co-executive director of the Anne Arundel Conflict Resolution Center from 1995 to 1998.

Ochs also spent every summer Saturday evening onstage for seven years, hosting the Quiet Waters concert series. Though the park hired the musicians, Max helped select them.

Without any warning, last summer the county’s director of parks and recreation, Dennis Callahan, fired Max as volunteer host.

You might have expected Max to protest. After all, he was one of the anti-Vietnam War protesters who stopped New York City’s Armed Forces Day parade in 1965. Though his firing outraged many, Max wrote a letter of apology to the county executive and moved on.

What did he apologize for? Some published reports say the angry letter Callahan cited complained both about comments Max made on stage and about a rarely heard original verse of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” he sang. Max had commented that he didn’t think President George W. Bush liked to read and he thought the way the president reads a speech sounded like he didn’t read very well.

“I wasn’t practicing what I preach,” says Max.” One of the principles I teach is to attack the problem, not the person. I disagree strongly with the policies of this administration. But I was stepping down to a personal attack.” For him, apologizing opened the door to many conversations about an important principle of conflict resolution.

But moving on hasn’t freed up enough time for Ochs, who explains his departure from the 333 saying, “I really want to do some creative things.”

“We never realized how much Max was doing,” says 333 volunteer Chuck Fullerton, who’s never missed the coffeehouse himself. Though Ochs had acts booked for a year in advance, the amount of work surprised the committee that tried to take it up.

Brushes with Fame

Writer, singer and guitar player, Ochs has always been doing something creative. He reports teaching ‘Country Joe’ McDonnell to play in open tunings. He played with Buzzy Linhart in the band Seventh Sons. They played in a peace concert at Carnegie Hall, and Bob Dylan joined them onstage. Ochs briefly met McDonald’s girlfriend Janis — as in Joplin. He played guitar with Jerry Garcia at Garcia’s house. He’s on a recorded anthology of guitar players. “I always felt like a little footnote guy,” he says.

In 2002 he played in a blues festival in Japan. And he even played a cameo in the story of the blues.

Mississippi John Hurt is famous. But when Max first heard Hurt, none of his new young fans knew whether he was alive or dead. They just had some old 78rpm records. When Max got the call, “We’ve found Mississippi John Hurt,” there was nothing more important in the world, and he “ran down to Dick Spottswood’s house and got on a train.”

Harpe explains: “Had it not been for these self-made musicologists, these old guys would have remained obscure. The only records they’d have made would have been those 78s.” But the blues mafia brought many of them back into the limelight: Son House, Robert Wilkins, Booker T. Washington White. “These old guys ended up with a brief moment of fame and glory.

“Max was right smack-dab in the middle of this. Not a mover and shaker, but right in the middle of all this, doing his own thing, writing poetry and a novel,” says Harpe.

Noted folksinger Phil Ochs, Max’s late cousin, didn’t get all the talent in the family. “Of all the people I play with, I enjoy playing with him more than any other,” Harpe continues. “He knows the music so well, when we play together intuition is rampant. Each knows where the other is going. That’s hard, especially when music doesn’t have a Western structure, and you have to have almost a sixth sense about it.”

As much as his musical talents Ochs’ personal style has shaped the 333.

As much as his musical talents Ochs’ personal style has shaped the 333.

“He has a deep philosophy that deals with the goodness of human beings,” says Yevola Peters, mentor to a generation of community activists and Ochs’ supervisor at the Community Action Partnership. “He believes so strongly in what is right and that people will rise to the occasion to do the right thing. He has a lot of faith in people.”

Perhaps that faith in humanity is Ochs’ secret ingredient. “What draws audiences to some places more than others is mysterious,” Muir reflects, pondering Ochs’ success. “He has attracted helpers. It seems like that’s always an aspect of a successful venue, that the person has drawn others to help with the project.

Suzanne Ochs agrees that he has a “very, very loyal crew. He never has to call or remind people. It runs so smoothly. That has something to do with Max’s leadership style. He’s not a micromanager. The people at the door and at the food table do it their own way. He doesn’t have a critical bone in his body. That’s the best kind of leader. Someone has an idea and he says ‘Try it.’”

To both Muir and Suzanne Ochs, the coffeehouse has been like a child to Max. Says Muir, “It’s healthy to pass it into someone else’s hands. It’s hopeful to think it will carry on as strongly. It’s a tribute to the way he’s done it that he’s done a good job raising it. Some places don’t survive that transition, but I’ll bet this does.”

Says Ochs: “It’s sort of like birthing a child. You have to let it go. It’s now somebody else’s baby.”

Whose baby will it be?

“I suggested to Janie Meneely that she talk with Max because he was looking for someone to take over the reins of the 333,” says Harpe. “She’s pretty open minded, as Max was. It was never just the kind of music he and I do. He brought in all sorts of things, and that’s what I’m hoping she’ll do.”

“It’s going to be different,” says Fullerton. “But I have faith we will keep the quality up.”

See 8 Days a Week for Ochs’ 333 finale.

See 8 Days a Week for Ochs’ 333 finale.

About the Author

Lucy Oppenheim, a freelance copy editor, an activist and an aspiring writer, lives in Annapolis.

to the top