Volume 12, Issue 11 ~ March 11-17, 2004

|

|

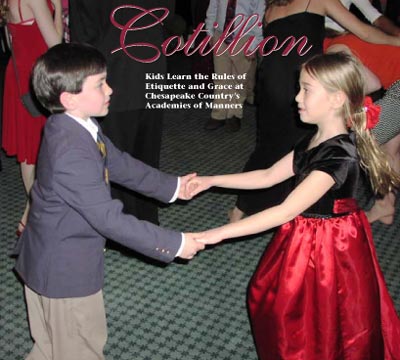

by Vivian I. Zumstein

Apprehension hangs in the air as 74 young children and their parents mill about St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Prince Frederick. In contrast to the bitter cold of the January evening, it is hot and stuffy in the crowded vestibule. Dressed to the nines, little girls fidget with unfamiliar white gloves. Boys rotate their necks inside collared shirts and, when their parents aren’t watching, tug at the ties pressing against their throats. “I can’t breathe!” wails one rebellious boy as his father snugs a loosened knot back up.

At precisely five o’clock, order emerges. Adult chaperones segregate boys and girls into two lines, and Tidewater Cotillion kicks off for 2004. It’s the first of six sessions for children in third through fifth grade. The older class for sixth through ninth graders begins at 6:30.

Cotillion opens, as it does every week, with a receiving line. One by one, the children step up to a line of adult strangers. Panic stricken, most stare at the ground to help them slip through unnoticed. The first adult in line explains, “You need to give me a firm handshake and look me in the eye. Then say Good evening, my name is and tell me your first and last name.”

Many children struggle. They offer a limp hand, shift their eyes away and whisper their names. The adults bend low, offering such gentle critiques as Pretty good eye contact, but please speak up a little. Despite the kind guidance, the children tremble.

After several unsure children shuffle through, a tall, blonde boy strides up. He fixes the chaperone with bright blue eyes, thrusts out his hand and delivers a wide grin. Then, in a clear, confident voice, he says “Good evening. My name is Derek Johnson.” The contrast is striking. I recognize him as a veteran of three years of cotillion.

A surprise comes at the end of the receiving line gauntlet. Like a spider ready to ambush a fly, the instructor, Katherine Mason, waits. Just as the children think the worst is over, Mason pairs the boys with the girls.

“Take this lady’s hand and escort her to her chair,” she directs a boy. He recoils, disbelief flooding his freckled face. Surely she’s joking! Touch a girl? Mason couldn’t evoke more revulsion if she’d handed him a glass and demanded, Here, drink this poison. The boy hesitates, hoping for rescue, but there’s no parent nearby to beg for mercy. With evident resignation, he stretches out his hand until he just touches the girl’s gloved fingertips. The lad leads her to the nearest chair where, without a word, he deposits her before fleeing to join the safety of the other boys on the opposite side of the room.

Kids Need Their Vegetables

Why would any parent subject her child to such torment?

Simple. In a world becoming more casual yet more competitive, young people with self-confidence and social graces stand out. They enjoy an edge over their peers in interviews for both jobs and prestigious university programs. Polish makes a difference.

Cotillion is social education. “The primary goals are to teach the children self respect, respect for others and self-confidence,” explains Dawn Szot, Chairwoman of the Tidewater Cotillion. “The program also hones social skills and teaches children to be comfortable from the least to the most formal social setting.”

Parents able to foresee the social skills their children will need as adults recognize the value of cotillion. Only the rare household can emulate the formal yet enjoyable atmosphere of cotillion. It’s an even more unusual child who willingly learns social etiquette at home when the world is so casual.

Can a child grow into a mature, responsible, successful adult without attending cotillion? Of course. It may just take more time and, in the long run, be harder on both parent and child.

“I liken it to making your kids eat vegetables,” says Szot. “They may not like it at first, but it is good for them.”

Cotillion Comes to Calvert

In 1995, Szot decided to send her two daughters to etiquette classes. “I wanted someone from outside the family to confirm the values I was trying to teach my children at home,” she recalls.

To her dismay, the closest course was a two-hour drive away. So Szot imported Jon D. Williams Cotillions (based in Denver) to Prince Frederick.

Launching the program was no easy task. “For the first seven years, I struggled to get the required attendance, 100 students,” says Szot, who often spent the week before classes twisting the arms of fence-sitters.

This year the program took off, drawing children from all over Calvert, St. Mary’s and Charles counties, as well as many who live in southern Anne Arundel County, even Annapolis. The increased enrollment is due in part to Monsignor Paul Dudziak, pastor at Jesus the Good Shepherd Catholic Church. In 2003, Dudziak saw a photo spread on cotillion in a local paper. He was impressed.

This fall, he joined with Szot to advertise cotillion through the church and school, Cardinal Hickey Academy. Enrollment blossomed. Of the 148 participants 38 (26 percent) are associated with Jesus the Good Shepherd.

“I supported the cotillion because I believe many parents are looking for extra help in raising young persons with personal confidence, social skills and good manners,” says Dudziak. “Young people with these qualities impress adults, including employers and university admission personnel.”

First Night Jitters

On cotillion’s first weekend, Mason has flown in from Denver. “Do you know how long you have to make a first impression?” she asks the students in this session. Blank stares from 74 pairs of eyes. “About 30 seconds,” she says, answering herself. “So you need to know how to do it right.”

Mason, young, attractive and professional, engages the kids with humor. She’s a comedic Miss Manners with a microphone. She delivers exaggerated demonstrations of social faux pas to grab the children’s attention, then she explains the correct way to do things.

“How about the hand shake? Do you give someone a hand like this?” Mason dangles a limp appendage in front of her body, shaking her arm a bit to make her hand flop. It appears as appealing as a dead fish. “Who wants to touch that?” Giggles ripple through the crowd.

Spicing her lessons with quips and anecdotes, she describes a good, firm handshake, engaging eye contact, proper posture, clear speech and using full names. The children learn while laughing.

Time to Dance

Even more painful than the receiving line or escorting a girl to a chair is dancing.

|

| Krista Keisu is paired up with a boy perhaps still uneasy with cotilion. |

Laughter explodes. “Oh, you laugh,” chides Mason, perusing the room, “But I have actually seen boys do this.”

For the girls’ part, Mason makes it clear that they may give only one answer to the boy. Yes. “There is yes and there is yes,” says Mason. “Heaving a huge sigh and rolling your eyes as you say yes is not acceptable. Think about how you’d like to be answered by someone you’ve asked to dance.”

Now the boys have to ask a girl to dance. A handful dash across the floor. These are actually the class’ biggest cowards. The rush is to get to a girl they know and can tolerate touching. Brothers become unusually fond of sisters when it is time to pick a dance partner.

Five solo boys slink onto the dance floor, trying to blend in with the couples. Five forlorn girls remain seated. Mason has anticipated this. Just the way a cowboy cuts cattle from a herd, she excises the reluctant boys from the crowd and supervises as they ask these girls to dance.

To put the kids at ease, Mason combines dances with games. A popular one has the children changing partners when she says, “Foxtrot.” A moment later, she stops the music. Any child without a partner gets eliminated. The last couple remaining wins. This game has normally reticent boys releasing one girl and scrambling to grab another, all amid shrieks of laughter. Nothing like a little competition to relieve inhibitions.

Practice Makes Perfect

By comparison, the older class is sophisticated. The children are more mature and have experience interacting with adults, but they still need polish. With many of these kids in the throes of puberty, the opposite sex no longer repels. It intrigues.

Why pay to send kids to cotillion year after year? Etiquette skills must be practiced to be mastered. Cotillion is not a one-time fix for social graces any more than one season of peewee football prepares a child to star on the high school team.

These older children demonstrate greater social ease, but veterans still stand out. They exude self-confidence and many of them, even the boys, have developed into good ballroom dancers. The kids no longer look at their feet; instead partners chat during dances. Having mastered basic steps, they enjoy learning new, flashy moves. Jitterbugging, a few couples strut their stuff with the windmill, hop-slide and lady’s underarm turn.

The best dancers, girls or boys, always get cut in on. In cotillion, girls as well as boys learn how not to be left out.

Inclusive and Effective

Just as the average child does not choose to eat vegetables, the average child does not choose to attend cotillion. Parents — more accurately mothers — choose to send them.

Some fathers resist. “They think it’s sissy,” reports Szot. “They fail to see the long-term value.” Also the word cotillion can elicit visions of privilege, stuffy “old boy” networks and elitism. However, nothing could be further from the truth with Jon D. Williams Cotillions.

|

| After surviving the receiving line, Christine Rice and Billy Clark are paired up. |

Families in Tidewater Cotillion represent a spectrum of Southern Maryland. Children come from both private and public schools, and several children are home schooled. One school, Bay Montessori in Lexington Park, includes the cost of cotillion in its tuition.

As children grow into poised young people, parents who send their children to cotillion, often over their offspring’s initial protest, see long-term results.

Employment websites abound with advice on how to nail an interview: Make eye contact, give a firm handshake, speak clearly and act confidently. The same websites exhort job applicants to avoid being nervous.

Laura McCrea, a regional field sales recruiter who lives in Owings, has been conducting job interviews for over five years. “The first impression at a job interview is critical. Professional appearance and polish are so, so important,” she says.

“Young people today really surprise me. Many dress unprofessionally and have a lackadaisical attitude. Even if a young man wears a suit, I can tell if he’s wearing it for the first time. Some give me a limp handshake, others slouch in the chair or ramble when answering questions,” she continues. “They haven’t been taught to deal with a structured social setting and their nervousness takes over.”

Cotillion graduates don’t have to think about handshakes or eye contact. These actions become second nature. If they interview over a meal, they will not be baffled when confronted with an array of cutlery. Instead they can focus on convincing the interviewer that they are right for the job. Possessing such skills gives a young person a competitive edge.

“When I am conducting an interview,” says McCrea, “I am really looking for what we call ‘quiet competence.’ That is something that stems from being self-confident.”

Tested at the Table

Parents, too, have been known to learn from Mason’s lessons.

At table etiquette class, children eye with suspicion the array of unfamiliar cutlery arranged on the table in front of them. Many have never dealt with more than a knife, fork and spoon. Mason explains the use of more of these than her students ever imagined. She always gets a rise when she gets to the fork for escargot. “Anybody know what escargot is?” she asks.

At least one child in each class thrills to inform the rest that, “It’s snails!” “Ohhhh … gross!” the kids react in unison. A few younger boys punctuate the response with gagging noises.

More common and troublesome than this little fork is who owns what on the table. Mason has a trick to solve that problem.

“How can you remember which bread plate belongs to you?” she asks. “Put your hands in front of you,” she directs. “Now touch the tips of your forefingers to the tips of your thumbs to make circles on both hands. Keep your other fingers straight. Do you see that you’ve made a lowercase b and d? Your left hand is b for bread plate and d on your right is for drink.”

“How can you remember which bread plate belongs to you?” she asks. “Put your hands in front of you,” she directs. “Now touch the tips of your forefingers to the tips of your thumbs to make circles on both hands. Keep your other fingers straight. Do you see that you’ve made a lowercase b and d? Your left hand is b for bread plate and d on your right is for drink.”This trick works. Last year, I went to a very formal dinner where the hotel squeezed 12 people into tables for 10. One place setting flowed into the next. After a pause, a brave soul ventured, “I wonder which glass is whose?” I laughed, held out my hands and taught them all to make bs and ds. Twelve middle-age adults sat making circles with their thumbs and forefingers to identify their plates and glasses. Everybody loved it. Nobody accidentally ate a neighbor’s bread.

Mother Knows Best

Denise Almaraz of Huntingtown wants those advantages for her two children, Luke (10) and Rebekah (eight). She works in information technology for an insurance company, and her husband Ralph is an independent electrician. In their solid middle-class family, Ralph surprised her by not resisting. His only response was, “Luke is going to kill you.”

Luke was a hard sell. “I thought it would be awful,” he says. “I was really nervous at the first class because I didn’t know what to do and I didn’t want to dance.” An excellent student and a standout athlete, Luke hates dressing up; he’s shy and he’s uncomfortable in new situations — all excellent reasons to attend cotillion.

Almaraz first tried to bribe him, but she admits that it finally came down to authority: “I am the mother and you are the child.”

Rebekah was just the opposite. “I didn’t have to convince her. I told her she was going to ‘princess classes’,” jokes Almaraz.

Almaraz’s reasons for sending her children mirror those of other parents. “I wanted to introduce them to culture, etiquette and manners,” she says. “They need to learn how to behave in public and to be good, mature citizens.” Thoughtfully, she adds, “I want to be proud of them.”

Grandmother Martina Fowler of Dunkirk volunteered to pay for her granddaughter, Krista Keisu (nine), to attend. “I thought it would help her overcome her shyness,” explains Fowler. “But there is so much more. I was totally unprepared for all the bonus gifts.” She cites children relating to the opposite sex, considering other’s feelings and learning basic ballroom steps.

Krista is less enthusiastic than her grandmother, but she, too, sees the benefits. “I didn’t want to come at first,” Krista admits. “But the first class wasn’t too bad. I didn’t like the part where the boys had to pick girls to dance. But I liked dancing the cucaracha and I like dressing up. I’ve learned a lot. I’m already more comfortable.”

The Belligerent Boy

The more resistant a child is to cotillion, the more the child needs the training. Resistance often stems from a discomfort with new situations. Better come to grips now than over a string of unsuccessful job interviews.

Mason excels in winning over the reluctant youngster, but every now and then a truly belligerent child surfaces. A few years ago one turned up at Tidewater Cotillion.

The 11-year-old boy carpooled with another family. At the door, the mother driving gave her three boys a quick going over: brushing off a little lint here, straightening a tie there. When she reached to snug up this boy’s tie, he swatted her hand away, wrenched his tie knot three inches from his neck and fastened her with a malevolent glare, daring her to tighten it.

The boy tried to evade the receiving line, too, but eventually he shuffled through, tie knot dangling, eyes studying his feet and fists shoved deep into his trouser pockets. He ignored the chaperones, refused to escort a lady and sat on his chair sideways, his back to the class.

|

| Cotillion boys hide on their side of the room. |

Mason overlooked his truculence. She launched into her comedy routine, and the class responding with predictable mirth. After a very funny line and peals of laughter, the rebel’s shoulders quivered. With visible effort, he stilled his body into sullenness.

Mason continued on a roll, with the class eating out of her hand. Again and again, the boy struggled to stifle laughs. He battled for another 10 minutes before capitulating. Turning in his seat, he watched as well as listened.

Now in his third year of cotillion, this boy looks forward to the classes. Not only Mason won this Round.

Graduation Night

On February 28, Tidewater Cotillion students show their stuff.

When the younger class teaches their parents to dance, ambitious pint-sized sons try to pull off the underarm turn with their 5'8" mothers. They find the side chassé works much better. Daughters giggle as they dance with their dads.

The older students put their knowledge to the test with a dinner party at the Old South Country Club in Lothian. The children pair up, the boys escorting and seating the girls on their right. Under dimmed lights and in a formal setting, they deal with an assortment of cutlery. The veterans again stand out. When the salad arrives, they know to start with the outside fork. New students watch and emulate.

Pleasant conversation fills the club. These kids are at ease. Only one surprise arrives. Many new students don’t know what to make of the sorbet delivered between the salad and main course. “It’s to cleanse your palate, silly,” explains a girl. Everyone eats it. It’s sweet and it’s not escargot.

The kids make Mason proud. When a girl excuses herself, all the boys stand for her departure and her return. Chaperones applaud.

After dinner, when these students dance with parents, height mismatches are fewer. Boys whirl and twirl their mothers across the floor, and dads get left in the dust.

Nicholas Bowen, a sixth grader in his fifth year of cotillion, admits he likes cotillion. “Lots of my friends from school have to come. I like the dancing, especially the jitterbug. I also like meeting new people.”

Another boy, a seventh grader and a cotillion veteran, wants to remain anonymous. “I don’t want my friends at school to think I’m a sissy for liking cotillion. They think it’s stupid, but I like it,” he confesses.

New students Luke and Krista have divergent opinions. Krista, like most girls, is a convert. “I definitely want to come back next year. I want to be more comfortable when I get older dancing with boys,” she says.

Luke struggles. It takes more than one season for the average boy to feel comfortable, even longer to admit that he might enjoy cotillion.

“Well, I might come back next year,” he hedges. “Dancing with girls wasn’t too bad, but it wasn’t great,” reserving enthusiasm for “the drinks and cookies.”

Luke’s fate, of course, rests with his mother. Almaraz says she has already seen improvements in how he responds to adults. She wants for her children the self-confidence she has seen in cotillion veterans, but she’ll have to decide if the fight is worth it.

Fowler, however, has no reservations. She plans to pay cotillion tuition for both Krista and next year for younger brother Zachary.

Manners Around the Bay

Cotillion is slowly coming to Bay Country. Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts offers Cotillion with A Twist every other Friday night for five sessions January through March for children in fifth through eighth grade. This year, third and fourth graders attended Mini Cotillion on two Saturday evenings in January.

In Odenton, Liz Hasken tried to establish a new Jon D. Williams Cotillion at the Waugh Chapel Community Center this year. “It’s hard to start a new program,” she laments. Public schools cannot distribute flyers for cotillion because it is a for-profit organization. “We almost had enough kids. I’ll try again next year.”

At the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Jon D. Williams presents cotillion for the cadets. Mids and staffers at the U.S. Naval Academy learn in a curriculum called The Midshipman as a Public Figure. Subjects are military protocol, dining skills, dance, speech lessons, reception and receiving line protocol as well as appropriate military and civilian dress.

“Our program endeavors to provide the midshipmen protocol and etiquette skills that will enable them to move with ease and comfort in their professional and personal lives,” says Anna Hart, Academy social director.

Plan ahead for cotillion January 2005: www.cotillion.com.

Jon D. Williams Cotillion $145 (3rd-5th) and $175 (6th-9th)

–In Southern Maryland: Dawn Szot, 301-884-5982

–In Gambrills/Crofton: Liz Hasken, 443-995-2434

–In Annapolis: Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts ($80 for grades 5th-8th; $30, 3rd-4th): 410-263-5544 • www.marylandhall.org.

About the Author

About the Author

Vivian Zumstein is a retired Navy commander and mother of four well-mannered cotillion veterans. Hailing from the Puget Sound area of Washington State, she has lived for 12 years in Calvert County, where she coaches soccer, volunteers in the local schools and communes with nature.

to the top

Last updated March 12, 2004 @ 1:37am.