You Don’t Have to Own a Boat to See the Sights — and Lights

Story and photos by Michael R. Kelley

In Chesapeake Country, September ushers in the best season for seeing the sights.

In Chesapeake Country, September ushers in the best season for seeing the sights.

When we moved to our Bayside house 18 months ago, my wife Robin and I decided to resist the urge to buy a boat — at least for a year or so. We enjoy watching the water, but we don’t care much about fishing, water-skiing or other water-borne activities. So we figured we really didn’t need a boat. Then again, no one really needs a boat unless you use it to earn a living. Nevertheless, living on the water’s edge certainly makes you think about boats a lot, whether you own one or not.

“Make friends with a boat owner,” Robin often joked.

Last year, we took a sailing lesson from the Chesapeake Sailing School and Charters out of Herrington Harbour South. Our class finished with a two-hour sail. We got quite wet on that very windy Sunday, and we learned that if you really want to go up to the West River for lunch, you need a powerboat. Sailboats just aren’t the best mode of transportation from here to there and back again in a set period of time.

For most of last summer’s lazy weekends, we spent a lot of time sitting on our porch watching the boats on the Bay and counting the osprey and red-winged blackbirds. Instead of going out on the water, we contented ourselves cruising along the back roads of Bay Country, from Solomons to Annapolis, checking out marinas, restaurants, plant nurseries and vegetable stands by land. We had plenty of water views at home and from the many waterside restaurant tables up and down the Western Shore.

Still the water lured us.

Besides Fishing

With spring, we cruised out of Deale and across the Bay with Capt. Jim Brincefield and a boatload of partygoers from the on-line news group, Tidalfish, to enjoy a buffet supper at Harrison’s on Tilghman Island, some Bluegrass music and a charity raffle. There were more of us than Jim could take aboard Jil Carrie, so Capt. Frank Carver took the rest of the group on his trawler, Loosen Up.

These charter captains and others like them in Deale, Breezy Point, Chesapeake Beach and Solomons provide an inexpensive way for landlubbers to get out on the water and enjoy a day of fishing and friendship. Usually, these captains run serious fishing charters, leaving either early in the morning or at sunset to spend many hours at one or two favorite spots where the fish are biting. They do the best they can to assure that everyone comes home with a good fish story or two. Ours was the rare destination cruise on a charter fishing boat, a chance to enjoy the Bay before the start of the rockfish season.

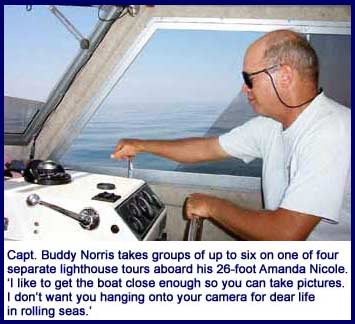

This summer, we were again feeling an itch to get out on the water when I found — in these very pages — Capt. Buddy Norris and his Lighthouse Legacy Charters. Norris grew up around Chesapeake Bay and its lighthouses. He photographs them, tells stories about them and has even slept in a couple of them as a youngster. Now he takes from two to six folks on his 26-foot diesel inboard, Amanda Nicole, on one of four separate lighthouse tours.

“These old lighthouses hold such a fascination for me,” Capt. Buddy told me when I telephoned to learn more about the tours. “Years ago, people actually lived in them,” he added.

Both my wife and I grew up in Washington and spent many a summer’s day swimming or boating on the Bay, but neither of us had ever been up close to any of the Chesapeake lighthouses built out over water.

“That’s a great idea,” said Robin.

I signed us up.

Water View

On August 2, we set out from Breezy Point.

Capt. Buddy prefers not to conduct lighthouse tours on weekends when the Bay is crowded with boaters. It’s just too hard to take good photos when your boat is rocking in multiple wakes. For the same reason, he also postpones trips if the weather will make the Bay too choppy.

“I like to get the boat close enough to these old structures so you can take pictures from various angles,” he told me. “I don’t want you hanging onto your camera for dear life in rolling seas.”

August 2 was billed as a very hot but calm day, and the forecasters got it right for a change. Temperatures hit 100 degrees in Washington, but the Bay was like glass and perfect for our purposes. I worried that it could be uncomfortably hot on board, but with the water temperature at 87 degrees, it was very comfortable in the cabin and on the canopy-shaded deck when the boat was moving.

We set out at the civilized hour of 9:30am, heading north up the Western Shore. This was to be a bit of a sightseeing tour as well as a lighthouse tour, for we were eager to see the shore we travel so often by land from the perspective of the sea. We went past the Navy installation at Randle Cliffs — much more forbidding when viewed from the sea than from the road — on past the marina and waterside townhouses of Chesapeake Beach and by the little town of North Beach with its fishing pier and signature blue water tank. We sighted our house and took an obligatory picture or two from the boater’s point of view.

The Bay is very shallow along this stretch of coastline, and jellyfish were plentiful. I wanted the captain to steer the boat closer to shore so I could get a better picture of our house. But he had his eyes fixed on the depth finder.

“Folks who bring a boat in here must know where the channel is. I don’t have a clue,” he said. Moving the boat ever so slowly, he eased it out into deeper water.

Farther north, we passed through Herring Bay, where we had taken our sailing lesson last summer. We passed the inlet for Deale at Rockhold Creek, the homes at Shady Side and the West and South river inlets.

Calling on Thomas Point Lighthouse

Calling on Thomas Point Lighthouse

Now, we were in full view of our first destination, the screw-pile lighthouse at Thomas Point Shoal, a mile or so off the Western Shore coast near the mouth of the South River.

As you might expect on a typical August day on the Chesapeake, there was a slight haze in the air. The sky was a clear blue overhead as we neared the Thomas Point Light, but the haze made the Bay Bridge and a couple of big freighters waiting in the channel near it seem enveloped in fog. Close up, the lighthouse was bathed in sunlight: a bright white wooden cottage with a red tin roof perched high on its iron screw-piles, the last working lighthouse of this design still at its original spot in the Bay.

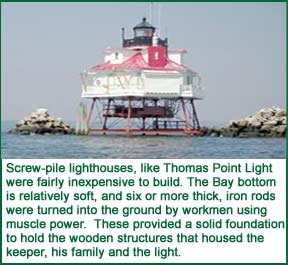

The screw-pile lighthouse was relatively inexpensive to build when Thomas Point Light was constructed in 1875. Thick iron rods with screw-like spirals cut or forged into their lower ends were essentially turned into the ground by four or more workmen using muscle power and a kind of lever. The Bay bottom is relatively soft, and six or more of these iron rods could be screwed far enough into the substrate to provide a solid foundation of iron pilings. These pilings hold the wrought iron foundation for the ornate wooden structure that would house the keeper, and in the early days, his wife and children. In most cases, the wooden walls of the cottages were fabricated on land, then taken by boat to the screw-pile foundation for assembly.

These graceful cottages perched high in the air with their dormer windows, filigreed wooden railings and almost lacy wrought iron supports had a kitchen area, a living room and upstairs bedrooms. The screw-pile Drum Point Light, now reconstructed at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons and open for tours, even had a dining room.

We idled in the water moving slowly from one side of the lighthouse to the other, getting a good view from a variety of angles. Hanging out over the edge on one side is a box-like wooden appendage. “That’s where the toilet is,” Capt. Buddy said. Sure enough, it’s a true ‘outhouse’ with a direct line of sight to the waters below.

On another side, we saw the now automated foghorn’s two-hole sensor. The captain explained how the sensor sends a beam of light out of one hole: “When there’s fog in the air, that light beam gets reflected back to the sensor in the other hole, which then activates the horn.”

Each lighthouse has its own blink and horn sequence, some every three seconds, some every six, and so forth. Seasoned mariners can identify a lighthouse by the interval of light or horn blasts.

Beautiful, even arresting, as they were, the screw-pile lighthouses of the Chesapeake all had a major problem. Their foundations were not always strong enough to withstand the ice floes that occasionally break free and surge through the Bay. Thomas Point Light almost succumbed to the ice in early 1877 and is now protected with stone riprap, which requires costly regular maintenance.

The lighthouse keepers feared ice even more than loneliness over the years. It threatened their lives, could shut down their supply boats and cut them off from the shore. Today all of the Bay’s lighthouses are automated and unmanned, but it was Thomas Point, with its screw-pile design most susceptible to ice damage, that in 1986 was the last of the Bay’s lighthouses to get automation equipment.

Because it is so close to Annapolis and communities along the Severn, South and West rivers, Thomas Point Shoal Light is probably the most photographed of all the Chesapeake’s lighthouses. It is also one of the most charming lighthouses still operating on the Bay. It warns of the shoal’s dangers today just as it has for 127 years.

Crossing to Bloody Point

Crossing to Bloody Point

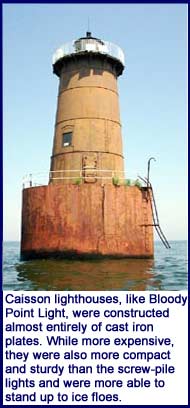

To design a lighthouse that could stand up to the Chesapeake’s occasional raging ice, the U.S. Lighthouse Board in the early 1880s authorized the caisson style lighthouse, constructed almost entirely of cast iron plates, and far more compact and sturdy than the screw-pile design. Able for the most part to stand up to the ice floes, it was also more expensive to build than the screw-pile design.

Leaving the Thomas Point Shoal Light behind, we headed across the Bay to the Eastern Shore and the southern tip of Kent Island so we could get a close look at the caisson lighthouse at Bloody Point.

The Bloody Point Light at the mouth of Eastern Bay, an inlet just south of Kent Island, is a cast iron tower mounted on a foundation of iron and concrete. The caisson design goes back to the bridge pilings used to construct London’s Westminster Bridge in the first half of the 18th century.

The caisson itself is essentially a hollow iron cylinder towed to the site and then sunk down into the bottom. In 1882, workmen filled it with concrete and rocks to help it sink and to weigh it down. On top of this concrete filler, they constructed a cylindrical tower out of cast iron panels to form the house itself and to support the light on top.

The caisson lighthouses aren’t nearly as beautiful or charming as the screw-pile cottages on iron stilts. And it’s hard to imagine what life was like inside one of these Victorian-era tin cans. Today’s automated lighthouses have boarded up windows, but when they were manned, these cylinders had windows on various floors and an open walkway with an iron safety railing around the outside top and the bottom floors. A cast iron stove provided warmth in the winter, but the summer heat must have forced the keepers out onto the shadeless decks — or perhaps into the water for a cooling swim.

“Notice how it leans a little,” Capt. Buddy said.

The Light at Bloody Point began to settle into the Bay’s bottom a couple of years after it was constructed. In the mid 1880s, workers tried to dredge down on the high side to sink the caisson further into the substrate to level it. But their efforts proved futile, and the lighthouse has a distinctive lean to this day. This must have been yet another annoying nuisance for the keepers who lived here at Bloody Point.

Up close, the lighthouse shows years of neglect. The caisson is cracked and weeds have taken root on the lower deck. Despite the neglect, Bloody Point Light has been right here in these waters for 120 years, withstanding tides, ice and hurricanes, guiding mariners around Bloody Point bar. It deserves to show its age.

From Bloody Point, we headed south to Sharps Island Light, one of the Bay’s true curiosities. “Get ready for a really unusual sight,” our captain advised.

Curiosity Sharpened

Curiosity Sharpened

Sharps Island was once an inhabited stretch of land protruding into the Bay south of the mouth of the Choptank River and roughly due east of Breezy Point. Its 700 or so acres of farmland and swamp grass long ago yielded to the erosion that has engulfed or threatened other Bay islands.

The first lighthouse to mark Sharps Island was built on shore in 1838. It was disassembled and moved farther inland in the 1840s because erosion was eating away the shoreline. But the new location proved untenable, and a couple of decades later, the Chesapeake retook that location and the original lighthouse with it.

In 1866, Sharps Island got its second lighthouse, a screw-pile style constructed in the Bay just off the Island. Its foundation was swept out from under it by an ice floe in 1881. Luckily its two keepers hung on to the relatively intact cottage, which floated for more than 16 hours among the ice blocks. They were able to save the light fixture and get to shore in the dory, living to tell an amazing tale.

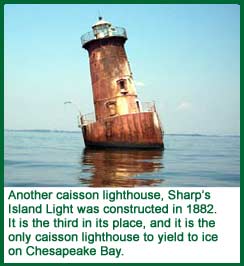

The replacement caisson style lighthouse, Sharps Island’s third light, withstood subsequent ice floes for years after its construction in 1882. But today, it leans like the Tower of Pisa, the only caisson-style lighthouse ever to yield to the Bay’s ice floes. A huge storm with blocks of ice in 1977 pushed the light over to its current position.

Repairs have straightened the light inside so that it shines perpendicular to the water and off-center from the iron cylinder itself. Fully automated and listing in what seems to be an untenably precarious position, Sharps Island Light and foghorn still function to this day, though the Bay has long ago reclaimed all of Sharps Island.

After another round of picture taking, we headed off to Tilghman Island and Harrison’s restaurant for lunch.

Full of delicacies from the Bay, we returned to Sharps Island Light for a last look, some more pictures and a final run across the Bay to Breezy Point. We had been out for six memorable, educational and enjoyable hours.

After this trip, we’re more convinced than ever that arranging for a licensed captain to take us out on the Bay — and do all the worrying and maintenance that boats demand — is the best way for us to enjoy Chesapeake boating. Find out more about different lighthouse tours at www.lighthouselegacycharters.com.

There are a wealth of boating opportunities awaiting you in Chesapeake Country — even without owning a boat. Read about them in future issues of Bay Weekly.