|

|

Ocean Race is Coming Our Way Ocean Race is Coming Our Way

by Debbie Hough

Down in the winter doldrums?

Put the wind back in your sails by following the adventures of the Volvo Ocean Race.

Had a bad day out on the Bay? What’s your worst memory? No wind in your sails? Out of fuel? Local squall? Lightning storm? Choppy water? Seasick? Sunburn? No fish biting? Flies biting? Out of beer?

Wind in your hair and water in your shoes are the usual worst. The day’s struggles become lore to be retold after a shower, a sip and a sunset.

A bad day on the ocean is far worse. You haven’t been truly without wind until you’ve crossed the equatorial doldrums, a latitudinal dead zone for wind. And what good is wind if you’ve lost your sails to gales or your mast in a snow squall?

How about broken ribs, shattered knee caps, stitches at sea? Tropical downpours, sky-to-sea water spouts, maybe a man overboard while doing 30 knots in Antarctic waters? Perhaps a collision with a whale?

Ocean days don’t end at sunset. Instead, they are reconfigured and never-ending, with four-hour watches cycled with four hours off. Four hours is plenty of time to eat, rest, repair equipment and tend to the disaster of the day, all the while racing at full speed, in cramped quarters, across chaotic seas in all weather. Right? Now, repeat this scenario for nine months, and if you are still alive, you can consider yourself an ocean racer.

From Whitbread to Volvo Ocean Race From Whitbread to Volvo Ocean Race

The Volvo Ocean Race — the Whitbread Race for its first two decades — has been at sea since September 23, 2001, when the fleet launched from Southampton, United Kingdom.

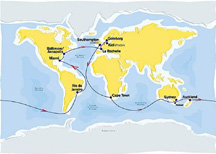

Eight yachts, each with 12-man crews, are competing in the nine-month endurance race. After Southampton, the round-the-world endeavor stops in 11 cities: Cape Town, South Africa; Sydney and Hobart, Australia; Auckland, New Zealand; Rio de Janeiro; Miami; Baltimore and Annapolis; La Rochelle, France; Goteborg, Sweden; and Kiel, Germany.

So far the fleet has covered 22,650 nautical miles. In the first four of the race’s nine legs, the ocean racers have spanned four continents, from Southampton to Rio de Janeiro. There, they are resting, regrouping and repairing before the 4,450-mile trek to Miami.

The race has always begun in England, where Whitbread was born as a contest for a couple of the British Royal Navy’s 55-foot yachts. Whitbread PLC, a British brewery and hospitality company, agreed to sponsor a race around the world.

An array of boats of various class, from 55 to 73 feet, joined in the first Whitbread in 1973-’74. Likewise, the crews represented a wide range of competitors: navy sailors, pleasure boaters and paratroopers, to name a few.

In the first race, a Mexican washing-machine manufacturer sailed the family yacht, Sayula II, across the churning seas to victory. The victory was hard-won, however. On route to Sydney, Sayula nearly surrendered to the sea when she capsized in storm-agitated waters. The tethered crew was washed overboard and had to haul themselves back aboard to press on to triumph. Three men on competing boats weren’t as lucky. Swept overboard in violent weather, they perished in the perilous seas.

The race quickly became an international contest. But after the 1998-’99 contest, Whitbread sought to sell the sponsorship rights of a worldwide event that had outgrown its advertising means.

Swedish auto maker and marine engine manufacturer Volvo purchased the rights to a race it saw as embodying the company’s creed: strength, endurance, teamwork, leading edge technology, safety, excitement and achievement.

Volvo’s Technical Edge

Volvo’s venture has resulted in the most sophisticated race to date. Each of the boats has state-of-the-art camera, video and computer equipment on board. The crews are required to supply the race committee with film footage and e-mails to enhance media coverage. Hence, the forward section of each boat houses a large Nera Saturn B communications dish to transmit video and data. The stern of the boat is adorned with a Nera Worldphone telephone link and an Inmarsat C for e-mail and weather updates.

Crew e-mail and photos reach people around the world via the Volvo website, adding to the worldwide interest and excitement. The boats have links to weather satellites to track changing patterns, improving safety and edge in tactical maneuvers.

Volvo is a stickler for safety. Before the race, each team practiced fast-turnabout survival drills. Safety checks are required at the start of each leg. Each boat is equipped with two 12-person orange liferafts, emergency rudders and crew-tethering devices. All crewmen wear emergency wrist beacons so men overboard can be tracked by satellite. Larger, buoyant, satellite-trackable beacons are immediately tossed to the spot where a sailor goes overboard. With good reason: falling overboard has been the biggest cause of Whitbread deaths.

|

|

Team SEB Before the race, each team practiced fast-turnabout survival drills.

photos ©Oskar Kihlborg, |

The Contenders

The eight boats battling in the race of extremes represent sponsoring syndicates from diverse nations. An assortment of skilled sailors from an equally diverse array of nationalities crew the various boats.

ASSA ABLOY carries the company name of the Swedish world leader in lock manufacturing, including Yale locks.

Djuice Dragons, the Norwegian entry, is sponsored by Telenor Mobile Communications and other corporations.

Illbruck Challenge represents a German manufacturer of building and automotive products.

Amer Sports One, sailed by men, and Amer Sports Too, sailed by women, are competing entries from Nautor Group, the builder of Swan racer-cruisers.

Team News Corp is an Australian entry of publishing giant Ruppert Murdock, who owns the New York Post and London Times, as well as the Fox Television Network and Fox Movie Studio.

Team SEB carries the name of her primary sponsor, Sweden’s largest bank.

Team Tyco is sponsored by a Bermuda-based company that owns ADT Security and also manufacturers goods from clothing hangers to underwater telecommunications systems.

What They Contend With

It takes a certain type of person to attempt a 32,000-mile trek with no shelter from adversity. From September to June, through all seasons and weather, the boats and crews are pushed to their mechanical and physical limits — and often beyond.

The boats are built for speed and safety, and not for comfort. For all of the technological equipment on board, there is no refrigerator or stove. Space is sacred and must be reserved for more important items, like the huge water ballast tanks that can carry more than 600 gallons of water to counter the heel of the boat and complement the keel.

Volvo Penta engines power the propellers and charge the batteries, as well as generate the all-important desalination plants that convert seawater to freshwater for drinking and food preparation. The crews dine on freeze-dried food and drink flat-tasting filtered water. Water for dinner boils on a single burner.

Even the most basic creature comforts are curtailed, with no hot showers and minimal bunkroom. Condensation from the water ballast systems hovering above the bunk area drips onto sleeping bags. Even these veteran sailors get seasick in vessels so light they are tossed about in virulent seas.

Equipment and sail repairs are made on board lest precious time and points be lost on unscheduled stopovers.

Such a detour befell Team Tyco in Leg 2. On her way to Sydney, rudder problems forced the boat to limp into Port Elizabeth, South Africa, at a slow seven knots. To meet the fleet for Leg 3, Team Tyco was barged to Sydney. That emergency repair means she’ll have to recoup a whole leg’s points later on.

Setbacks and tribulations of this sort are typical in this amazing race, where sailors must expect the unexpected, all the while enduring Spartan surroundings.

|

The fleet was pursued by a spry spout that danced along the ocean, unpredictably teasing.

photo © Jon Gundersen

|

Best-Laid Plans Meet Mother Nature

For all Volvo’s good intentions, danger is ever present. Most seasoned sea travelers have seen water spouts, natural phenomena of weather patterns converging to create water-formed tornados. Such funnels are best observed from a safe distance of 5 to 15 miles.

During the Sydney-to-Hobart leg, the fleet was pursued by a spry spout that danced along the ocean, unpredictably teasing from the close range of a mile or two. The yachts were sitting ducks. With no place to hide on the open water, they could only hope not to go down. The crews tethered themselves to their vessels with safety harnesses, warily watching as the spout darted in and out, randomly changing directions — leeward, windward, head-on.

Gunnar Krantz, of Team SEB, described it as a “giant vacuum cleaner coming down to suck away all the tiny boats littering the water.” It passed within 200 meters of some, with wind speeds of 63 knots recorded even at that distance. The damage was minimal, with only mainsails and jibs ripped and ruined.

That leg of the Volvo was incorporated into the Sydney-Hobart Race, an Australian competition with a 57-year history. Thus the Volvo racers competed in two races at one time. ASSA ABLOY won line honours.

Eerie as the waterspout was, it was no match for the disaster that befell the last Sydney-Hobart race, when six people met their doom in stormy seas. That tragedy resulted in stringent new safety rules.

|

Illbruck skipper John Kostecki, left, who captained Chesapeake Country’s Chessie Racing in the 1998-’99 Whitbread race, listens to directions from navigator Juan Vila.

photo © Ray Davies

|

Illbruck: Choice of the Chesapeake

The Chesapeake has no entry this year, but our region has a favorite son: Illbruck skipper John Kostecki, who skippered the Bay’s entry during the 1998-’99 Whitbread, sailing aboard Chessie Racing with the mythical mascot Chessie emblazoned on her side.

Kostecki has raced as a champion, winning three of the four legs thus far. But the overall win relies on cumulative points, so it is too soon for the Kostecki team to rest on their laurels.

The race is based on a 1-to-8-point system, with the points awarded based on the finish in each leg. A first-place finish earns the maximum of eight points, descending down to one for last place. Thus all competitors have a fair chance at winning throughout the race.

The prize for all this? A Waterford crystal trophy. The boat triumphant in the overall race wins the large crystal trophy, titled Fighting Finish, with smaller versions to the winners of each leg.

Illbruck has a nice lead with 29 points in the standings. The closest competitor is Amer Sports One, with 22 points. Still, a dramatic win or a woeful loss in any leg could instantly change the point standings.

Besides Kostecki, the Chesapeake is well represented. Juan Vila who crewed with Kostecki on Chessie, is with him again as navigator on Illbruck. Other Chesapeake sailors are Chris Larson on ASSA ABLOY, Terry Hutchinson on Djuice Dragons and Peter Pendleton on Amer Sports One.

Illbruck sailed like a witch across the Southern Ocean and won Leg 4 of the expedition, landing first in Rio. Around Cape Horn, Kostecki led the crew in outwitting notoriously wicked winds and using them to advantage. This marked Illbruck’s third leg to place first, with ASSA ABLOY in Leg 3 the only other boat to hold that distinction.

Kostecki’s anticipated antagonist on the Antarctic leg was Amer Sports One, skippered by Grant Dalton, with Paul Cayard on board as watch captain for the leg. Those veteran skippers made a unique power pairing. Dalton is the New Zealander who won the 1993-’94 Whitbread on NZ Endeavor. Cayard, the first American to win a Whitbread race, skippered EF Language to victory during the last Whitbread in 1998-’99. In that race, Dalton placed second on Merit Cup.

Race watchers looked to this champion collaboration to lead the race, but a risky wide route east around the Falkland Islands from Cape Horn placed them fourth.

|

| The entire crew aboard Djuice Dragons stopped to gaze at the first iceburg. |

The Southern Ocean: Swift and Severe

Growlers and icebergs and whales, oh my.

Whales and large partially submerged ice chunks, dubbed “growlers,” are the more stealthy of the mariners’ marauders since they don’t show on radar like the larger bergs.

“Even a small piece of ice … too small to show on radar … could easily ruin our day,” said Tyco’s navigator Steve Hayles. By sheer size, the bergs were a formidable force to fear, with hourly sightings of monsters up to eight miles wide and hundreds of yards high. That’s in southern hemisphere’s summer.

Tobogganing across the waves at 25 to 30 knots, under snowy conditions at night, allows only a few seconds reaction time. The ocean racers sailed in blind faith, hoping to avoid the frozen flotillas.

Most have, until this February, when Team News Corp became the first boat in Whitbread/Volvo history to collide with a berg. They hit a small growler while dodging a sea full of broken bergs. The damage wasn’t devastating, in the deadly sense, but their ruined rudder did wreck their chances to win that leg.

Sailing 2,000 miles from habitable land in the remotest spot on Earth compounds calamities. A severe snow squall set Team SEB into an uncontrolled jibe, breaking their mast. The demasting left them with a two-meter stub to which they attached a jury-rigged sail. Forced to retire from the leg, they hobbled the final 1,200 miles to Rio under mini sail and motor power.

Out of Auckland via the Great Circle, the sailors faced the icy waters of the south, rounding ominous Cape Horn and the biggest waves on the planet. With the faster winds generally farther south, boats edged low toward the most ice and the greatest risk. The Antarctic trek was like a downhill sleigh ride. Pushed by gale-force winds of up to 60 mph, boat speeds reached 30 knots. At such speeds, a boat would be “skipping like a rock” across the water, with the “spray flying like a fire hose” in your face, said Cayard.

Around the Horn, DJuice Dragons followed the Dalton-Cayard team east around the Falklands. Then, turning west, they alone pushed farther inshore along the South American coast. Their gamble paid off, propelling them to second place on the leg.

Rio de Janeiro and its tropical lure was great incentive to get past the Horn quickly. The sailors looked forward to the only ice being “in the Margaritas,” said Lisa McDonald, skipper of Amer Sports Too.

To optimize their efforts for winning times and safe passage, the teams abandoned sleep, all hands sailing round the clock.

Mark Rudiger, of ASSA ABLOY, reminded the crews that baptism of a devout ocean racer requires “one, crossing the equator for the first time; two, rounding the Horn; three, sailing in a snowstorm in the southern ocean; and four, sailing through ice packs in the middle of the night.” All boats met those requirements.

By the time the boats reached the South Atlantic tropics of Rio de Janeiro, Leg 4 had taken them 6,700 nautical miles.

|

Amer Sport Too sailors Carolijn Browe and Elizabeth Wardley crossed the Rio finish line with limp sails after bad luck with a low-pressure system.

photo © Carlo Borlenghi

|

Women’s Work Not Yet Done

Running with the big boys is one all-women yacht, Amer Sports Too. More than 80 women have crewed since the first Whitbread race in

1973-’74, with the first all-woman boat, Maiden, joining the race in 1989-’90. Working with less physical strength, Amer Sports Too’s crew is handicapped one extra sailor. Still, they’re hoping smart sailing on shorter, more tactical legs will take them out of last place.

Close calls and misfortune have toughened the race for Amer Sports Too. Skipper Lisa McDonald persevered while suffering a severe flu during the toughest leg, racing over the

Southern Ocean to Cape Horn.

In the earlier third leg, sailing near Australia, a huge impact reverberated through their hull. Soon the women saw the carnage of a large shark that hadn’t given way to a larger, sail-driven force.

Later in the day, the forestay broke, crippling their headsail. The women backtracked to Hobart, where repair crews discovered the extensive rudder damage inflicted by the shark.

The detour caused them to finish the leg 36 hours behind the rest of the fleet. Their spirits were buoyed at Auckland as they were greeted at 12:30am by throngs of zealous New Zealanders, marking the most spirited Kiwi welcome of this race.

Boat Designs Have Come Farr

New Zealand, a little island-nation in a big ocean, is over-represented in the Volvo race with 31 Kiwi sailors, a greater percentage than any other nationality. Living on an island, Kiwis learn their skills at a young age. At least 11 of the New Zealand competitors in this year’s Volvo are graduates of the Royal New Zealand Yacht Squadron.

As further proof of Kiwi dominance in the sailing world, consider Bruce Farr.

The boat designs have come far since the first Whitbread, when 19 assorted boats created by 12 designers competed. Now, one designer — Bruce Farr of the Annapolis firm Farr Yacht Design Ltd. — rules the race. Six of the eight boats competing this year were designed by the Farr team. The leader, Illbruck, is one.

Farr is a New Zealander who’s raced and refined dinghies since he was 12. With no formal education in boat design, he began drawing and building boats in New Zealand in the 1970s. He and Russ Bowler started their Annapolis design firm in 1981 and now employ an elite team of 15.

Before Farr, the Whitbread’s dominant boat was the maxi, an 80-foot-long, two-mast ketch that was sturdy yet fast. To meet the unique requirements of the Whitbread ocean race, Farr designed a shorter 60-foot, one-mast lightweight known as the Whitbread 60.

Farr’s first design of a Whitbread winner was the maxi UBS Switzerland that won the 1985-’86 race. Steinlager 2 and Fisher & Paykel, both maxis, placed first and second in the 1989-’90 Whitbread race. The 1993-’94 race was split between two classes, the maxi and Whitbread 60s. That race saw Farr’s designs, both maxis and 60s, obliterate the competition. His maxis took first, second and third place. Seven other entries, all Whitbread 60s, were also his design, with Yamaha placing first in their category. Yamaha was skippered by Ross Field, who is Team News Corp’s navigator in this year’s race.

Renamed Volvo 60s, Farr’s Whitbread 60 design was chosen by this year’s race committee as the only style permitted in the race.

|

Stormy seas aboard the Illbruck.

photo © Ray Davies

|

Mourning a Mariner

Another New Zealander and Whitbread/Volvo patriarch was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to sailing. Sir Peter Blake sailed in five Whitbread races, winning the 1989-’90 Whitbread on Steinlager 2, nicknamed Big Red. Blake took every leg in that landslide defeat.

Blake continued on to further glory in the yachting world by winning the Jules Vern Trophy for sailing nonstop around the world in less than 80 days. Only two others have earned that trophy to date. Blake also brought the America’s Cup to New Zealand. As head of the 1995 Team New Zealand syndicate and on-board crew member, he helped defeat Dennis Conner’s Young America in a 5–0 sweep.

His death by misadventure last December disrupted this year’s race. Blake was murdered by bandits while on an environmental expedition on the Amazon in South America. Amer Sports One skipper Dalton called Blake “without a doubt the greatest yachtsman the world has ever seen.”

Closer to home, Blake was remembered by his first cousin, Bruce Wilson, yacht broker and owner of Wingfield Yachts in Tracys Landing.

“Typical of most Kiwis, Peter was a seat-of-the-pants type fella, probably remembered by his neighbors in the Bayswater area of Auckland, where he grew up, for waking up the neighborhood in the early morning hours building his first boat,” Wilson said.

New Zealand marked the passing of its native hero by declaring a national day of mourning, with flags flown at half staff. A memorial tribute was held in Australia to mark the start of Leg 3, with the boats mournfully maneuvering into a tight circle. Following a moment of silence, a wreath was thrown into the center as a sign of respect for this fallen hero of yachtsmen worldwide.

Coming Our Way

With four legs sailed, Illbruck is the boat to beat. Ahead are three months of sailing, with five legs and 10,050 nautical miles of ocean to traverse. The tactical challenges in the miles ahead include the tricky winds, or lack thereof, of Chesapeake Bay, not to mention the crab pots that litter our Bay’s often sneakily shallow depths.

On March 9, the racers start Leg 5 from Rio to Miami. That leg will again have the boats crossing the equator with its windless doldrums. Leg 6 departs Miami on April 14 for the 875-mile jaunt north and through Chesapeake Bay to Baltimore. As the racers pass Cape Hatteras, the graveyard of the Atlantic, they will have to contend with the notoriously shallow waters, as well as the Gulf Stream, which creates unpredictable weather patterns.

The boats are also expected to converge with migrating northern right whales, an endangered species that will be traveling up the East Coast to Georgia the same time as the racers. In hopes of preventing collisions, the National Oceanic and Atmopsheric Administration will be monitoring by satellite both the whales and the boats.

Depending on how Bay winds blow, on April 17 or 18 the boats will race up the Bay to arrive in Baltimore, crossing the finish line at Fort McHenry in time for the city’s 4th Annual Waterfront Festival in Inner Harbor. The last event drew 400,000 people.

Next comes Annapolis, with the boats sailing leisurely down Chesapeake Bay on April 26 and arriving before 5pm for the welcoming ceremony at City Dock.

It will be a heartfelt welcome, for the ocean race’s Annapolis stopover secures the city’s standing as America’s sailing capital, as well as buoying its economy and bond rating. The race has been an “international magnet for us,” says Annapolis Mayor Ellen Moyer, who as an alderman helped lure it here four years ago.

Like the last race, this year’s event is expected to attract half a million visitors who’ll spend $53 million in the region.

And get their money’s worth. It will be both “a people show and a boat show,” promised Gary Jobson, ESPN commentator for the race, in Annapolis on a recent visit to promote the race. Over the weekend in Annapolis, the Volvo crews will be around and accessible as the Maritime Festival turns City Dock into a sailors’ ball with colorful regattas, historic ships and traditional Chesapeake water craft.

At City Dock at 10am on Saturday, April 27, for example, the skippers give firsthand accounts of the race and answer questions.

See the fleet’s arrival April 26 and its departure April 28 along City Dock or from the sea wall at the Naval Academy. After Sunday’s 10am blessing of the fleet, the racers will head back to the Bay. Off Sandy Point State Park, the race restarts at 1pm.

Sandy Point is the only spot, besides Southampton, England, where a start can be seen from land. From above, many of the 50,000 walkers who cross the Bay Bridge in the Annual Bay Bridge Walk will have prime vantage as the boats race under the twin spans. Spectators by boat are also welcome.

From our waters, the Volvo crews begin the second half of this round-the-world race. From here, the North Atlantic lies ahead, along with unknown adventures and a return to chilly waters, unique winds and unpredictable currents. With the fair point system, it will still be anyone’s race.

Follow the Volvo Ocean Race at www.volvooceanrace.com, where you’ll also find times and dates for ESPN coverage. Chesapeake organizers have a site specific to the Bay’s events at www.vorchesapeake.org.

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|