I wanted to play that western swing music, and I got in with some guys who showed me and I was able to do it.

The year was 1934. The Great Depression was in full swing. The words rock ’n’ roll and bluegrass had not yet been applied to music. It would be 20 years before Elvis Presley would make his first hit record.

Radio and recorded music were in their infancy, but their popularity was growing. Still, 1934 was not far removed from old times, when music was mainly home-made in parlors and on front porches.

In Southern Maryland, 11-year-old Bill Marquess listened to the radio. He heard Roy Acuff and the Smoky Mountain Boys playing the Grand Ol’ Opry, broadcast on WSM all the way from Nashville, Tennessee. He heard the music and he felt the music in him.

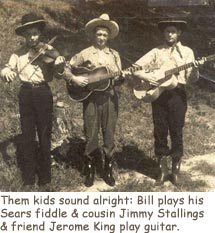

Soon he had a violin, ordered from the Sears and Roebuck catalog and delivered by truck to the Chesapeake Beach home where Bill lives today.

Before long the adolescent fiddler, accompanied on guitars by his cousin and a friend, were entertaining folks around the beach. Playing the tourist town in their cowboy suits, the trio earned pocket money for their efforts.

World War II delayed Bill’s dream of going on the road, but after serving in the army he embarked on a long road trip that took him way out West. There he discovered a new kind of music.

Western swing was a new sound that had its origins in pre-war Texas and Oklahoma but reached its peak of popularity in the ’40s and early ’50s. Its chief proponent was band leader and fiddler Bob Wills and his 18-piece band, the Texas Playboys. Wills and others played popular dance music and made it sound like jazz. The sound combined strings with horns, guitars and drums. Top western swing bands featured some of the finest musicians of the day and had immeasurable influence on generations of country musicians, including Hank Williams, Ray Price, Ernest Tubb and Merle Haggard.

Bill met Wills in Bakersfield, California, and sat in with the Playboys. That meeting led to a gig with another major group, The Riders of The Purple Sage. He also had stints with such notable groups as The Plainsmen and Al Krauss and the Oklahoma Wranglers.

He was a lone Easterner, perhaps the only Marylander, to make a name playing the genre. He traveled and toured, played on the radio and on record as well as before thousands of fans until, eventually, life on the road took its toll and he headed back East.

He was a lone Easterner, perhaps the only Marylander, to make a name playing the genre. He traveled and toured, played on the radio and on record as well as before thousands of fans until, eventually, life on the road took its toll and he headed back East.

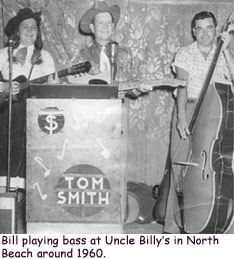

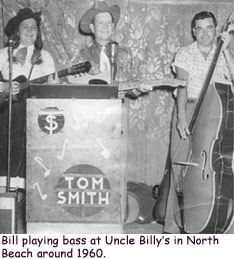

The beach towns of the late 1950s and 1960s offered opportunity for a talented musician. Joe Rose’s Musical Bar and Uncle Billy’s in North Beach were lively joints. The bands and the slot machines packed them in. There were crabs and beer, and people flocked from all over to have fun. Bill and the music were in the middle.

The demand for a musician of Bill’s talent remained strong in the ’70s and ’80s, but the trials of life as a working musician seemed to make staying close to home a more appealing option.

Even in the 2000s, stopping the music is not an option for Bill Marquess. Drop by the Prince Frederick Fire House or the Chapline Shopping Center, which sponsor open-mike sessions Friday evenings. You might catch him doing a rousing version of “Milk Cow Blues,” for free.

Bill has a wonderful voice that he likes to show off, and he values showmanship. When he steps up to the mike, he injects personality and humor into the performance. As he launches a version of “Orange Blossom Special” or “Take Me Back To Tulsa,” you’ll sense an energy in the air that comes from his confidence, pride and love for the music.

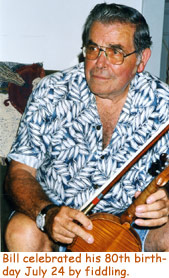

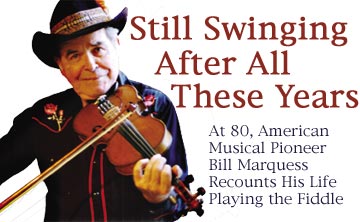

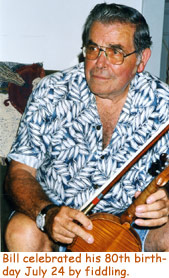

At age 80 — his birthday was July 24 — Bill swings. He says in all modesty, “I mastered the violin.”

Here, he has a bit more to say …

Getting the Handle of It

Listen to them kids; they sound alright.

I was 11 years old when I picked up the fiddle. It was 1934, and I wanted to play the violin. I wanted it bad. My mother told me, “If I get enough money ahead, I will by you a violin and a case.”

In those days, if you lived in the country there was Sears and Montgomery Wards catalogs, and you had to order it by mail. So she scraped up the money and ordered a violin from Sears.

It was just me and her living here in this house in Chesapeake Beach. I came from Anne Arundel County, Fairhaven, not too far from here, but we moved to Calvert. My father worked at Kanes Department Store in Washington, D.C. He was a floorwalker. But he died of double pneumonia when I was six months old. I never knew him.

The mail truck brought it down, and I could not get to it fast enough. I tore all the wrapping and the paper off, and it was the prettiest piece of furniture I had ever seen. Next to my mother, I thought it was the prettiest thing I had ever seen.

It was in my mind that I was gifted with music and that I was going to learn how to play. The strings were kind of rough, they were Bell-brand gut strings, and they didn’t last a long time. But I took it and I learned to play. It had a bow with it; it was horsehair but it was a cheap bow. I kept going until I got the handle of it. I used to play it like this, holding it down low below my shoulder instead of under the chin like you are supposed to.

My mother was always telling me to play it on the lower strings because when I played on the high strings it sounded like “squeaks and cat calls.” I told her, “Mother, that’s the way I do it. I want to play on all the strings.” But I tried to play on the lower strings to satisfy her.

A woman who was a friend of my mother’s, she asked, “Would you like to go the Peabody Institute in Baltimore to learn to read music?”

I told her “Ma’am, I don’t want to read. I want to play by ear.”

But she offered to take me and pay for it, so my mother talked me into it. I was about 12.

At Peabody Institute, they wanted you to learn how to read, but I just wanted to learn how to hold the violin and the bow. Well, they still wanted me to learn to read music. They showed me how to hold it properly, and they helped me learn to tune it right. I learned to read some, too, but I wanted to do it by ear, I guess. I was there for about two months and I could have stayed, but I wanted to get back to start my thing with my violin.

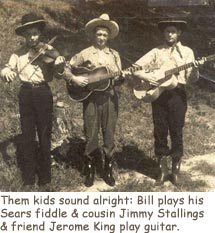

I had a cousin named Jimmy Stallings. He lived down the road and his father had a farm. He got an old, beat-up Sears S-hole guitar. We got together and we played around the area, just him and me. We’d sit around and play on porches like that. And we got to be pretty good and people would come around and say “Listen to them kids, they sound alright,” you know. I was about 13 and he was about 14 at the time.

I had a cousin named Jimmy Stallings. He lived down the road and his father had a farm. He got an old, beat-up Sears S-hole guitar. We got together and we played around the area, just him and me. We’d sit around and play on porches like that. And we got to be pretty good and people would come around and say “Listen to them kids, they sound alright,” you know. I was about 13 and he was about 14 at the time.

We got this other guy named Jerome King, and he did almost all of the lead work on the guitar. We bought red western shirts and black hats with white trim, tied underneath the chin. They bought their boots, but I didn’t get my boots right away. They were western boots with designs in the leather and you wore your pants down inside the boots so you could show off the design, and you wore the hats and everything else.

We’d go down to Chesapeake Beach Park — the park was up on the hill — and we’d go around and play for the people. The music we played was what we heard on the radio and records. We’d learn how to play by listening.

We would listen to the Grand Ol’ Opry down there in Tennessee. There was Roy Acuff and the Smokey Mountain Boys from over in Nashville. There were the Delmore Brothers. There were so many coming up at that time. There was WWVA, the Wheeling Jamboree from Wheeling, West Virginia. You know, I went up there and tried to get a job with the Wheeling Jamboree, but they were filled up. I was 18 or 19 years old. That was before the war.

Breaking Up, Breaking Out

I understand that you play a pretty fair fiddle.

When the war broke out, I was 18. I was drafted. The war broke up a lot of things, a lot of bands. I wanted to go on the road before the war, but I decided that I better not do that because I might be drafted.

My cousin Jimmy went into the service before I did. He was killed, and they named the Stallings-Williams American Legion Post after him and Jerry Williams, another boy from Chesapeake Beach. Jerry Williams was a bombardier, and his plane was shot down around the time of the landing at Normandy. Jimmy was a paratrooper.

I served some time overseas in the Pacific. We were going to invade the homeland of Japan, but they dropped the atomic bomb and I guess it saved me and a lot of other guys. We did go in as occupation troops under General MacArthur. I was over there about two and a half years.

While I was over there, I met a buck sergeant named Charlie Walker from Texas He had this deal that he was going to play on Armed Forces Radio. He needed a fiddle player, so he came looking for me. He said, “I understand that you play a pretty fair fiddle,” and I said, “Well, I do what I can.” And so we played on Armed Forces Radio, and it was broadcast and you could hear it in Japan, the Philippines, maybe even all the way to California.

After the war I came back here. I still had my Sears fiddle. My mother had taken care of it. I decided that I wanted to do something with it. But I got tired of hanging around here. So I decided to go on the road to Texas.

It was me and another guy, but he didn’t play any music; he just wanted to go. We had an old Ford; both of us would put gas in it and keep it up.

Along the Eastern Seaboard at that time, all you heard was the mountain music, hillbilly music and slow-drag country. When I got out West, I heard western swing bands, and I said to myself I want to learn that. I got with some guys that were familiar with that kind of music, and they taught me how to swing.

I went into this joint down there, and I heard music and I thought it was a jukebox but it was a band. I went up to the bandstand to ask the guys if they wanted a fiddle player. So the guy said, “Bring it in here.” So I started playing, and the next thing they wanted to hire me.

I worked with them on weekends for a while, but I wanted a job working every night. They told me “there ain’t no places around here that do that,” but I found a place out in the Texas panhandle, Abilene, and I started playing with a group there. They were playing every night except for Monday, and that’s when I started making my way.

I worked with them on weekends for a while, but I wanted a job working every night. They told me “there ain’t no places around here that do that,” but I found a place out in the Texas panhandle, Abilene, and I started playing with a group there. They were playing every night except for Monday, and that’s when I started making my way.

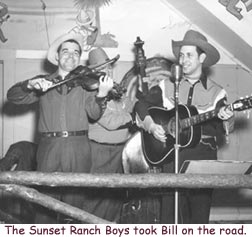

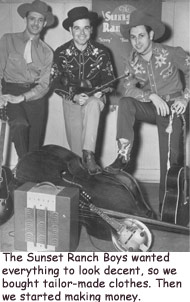

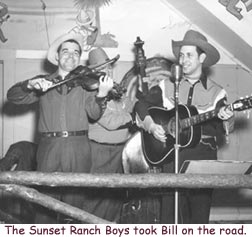

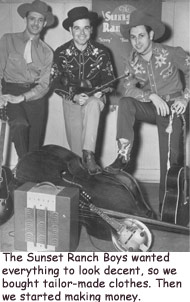

We were The Sunset Ranch Boys. They told me they did a lot of traveling and I said, “There ain’t nothing wrong with that.” They wanted everything to look decent, so we bought tailor-made clothes. Then we started making more money.

It was a guy named Carl who was the leader, and a Smith played lead guitar. We had an older guy named Heavy who played upright bass, and there was another guy who would sit in sometimes, I think his name was Ralph, who played the pedal steel guitar.

I played with them almost two years on the road. We were a traveling band. We had station wagons and buses like you take to the airport. We had to strap everything on the top. It wasn’t like it is now with the big buses they travel in.

Eventually they wanted to make a change. Everything changes. I could see it coming, so I decided to make a change, too, to see if I could find another group.

I found another group in Oklahoma. They were called The Plainsmen. They wore the western clothes, they had a gal singer, and there was a guy with an accordion. They played the western music, campfire music as it was called at the time, and some of the western swing stuff. In them days, there was an awful lot of accordion players in western bands.

I stayed with them for about four or five years. We would book theaters and auditoriums, and other bands would play in. We’d get a big thing going. The sponsors paid for most of it; you had to have the sponsors: Crazy Water Crystals, which was a laxative, Wheaties and John Deere tractors — of course there were a lot of farmers and ranchers we were playing to.

I met Bob Wills in Bakersfield, California. This guy who was not a musician told me he knew where I might look for work. It might have been the Beasly Ballroom. He said the guy is going places and his name is Bob Wills.

I said, “You don’t mean Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys?”

“That’s it,” he said, and I should go down and talk to Bob.

When they took a break, I went up to introduce myself. He asked me where I was from. I told him, “I’m from Maryland, but I’m from the southern part.”

He said that he didn’t know Maryland had a southern part. “Are you lost?”

I told him that I had been playing with some bands, touring, and that I was looking for work. He asked what I played and I told him the violin.

He said, “We don’t hire violin players. We play the fiddle. Very seldom do we ever get a classical violinist.” He was just teasing me. He asked if I had my fiddle and if I wanted to sit in on a couple songs, and I jumped on it.

He said, “We don’t hire violin players. We play the fiddle. Very seldom do we ever get a classical violinist.” He was just teasing me. He asked if I had my fiddle and if I wanted to sit in on a couple songs, and I jumped on it.

He introduced me by saying, “We got a young fella from, what’s that state, oh yea, south Maryland. I think he’s lost. We are gonna do a song and let him see what he can do. It’s called ‘Take Me to Tulsa.’ Ahhhha, let’s go fellows.”

And I started out on it.

You know people sometimes criticize him when they hear him play on records or CDs. He’ll say “Ahhhha, come on in Jody.” He’ll talk a lot, but that was the showman in him. Someone asked him why he would say “Ahhhha,” and stuff like that. He said “When I’m playing up on the bandstand and I see a cute thing go by and she looks up and gives me those big blue eyes, I just say Ahhhha.”

Later on he said, “You play a pretty good violin … I mean fiddle. I know a fella who might could use you.” So he gave me the name of Floyd Willie, who had a group called The Riders of the Purple Sage.

I called Floyd Willie, and he told me to bring my instrument for a tryout. They were a vocal trio; they played campfire music too, just like the Sons of the Pioneers. They needed a background fiddler. He told me that I was a good background fiddle player and I played nice and smooth. His other fiddler had a problem and had to leave, but I got along with them and played for about four years.

Everything was changing. You could see the changes coming.

It was a nerve-wracking job. It paid good money, but you had to be on time, you had to do this and you had to do that and you had to be right. I played with different bands that would be watching to see if I was going to make a mistake.

It can be hard to play in front of an auditorium full of people. Sometimes before going on the bandstand, I had to get a swallow out of the bottle. A lot of guys did it. Settle your nerves.

I had an interesting life playing with western swing bands, and after a long time on the road, you think it is a picnic. But when you get down to it, it’s not what you think. You might be here today and gone somewhere else the next day.

So after a while I thought I would take a trip back East.

During all that time, I never met any other musicians from the East Coast. I was looking to see if I could see anyone playing from Maryland.

Back to the Beaches

Man, they was hot times then.

When I came back home there was a place in North Beach called Joe Rose’s Musical Bar. It was across the street from Uncle Billy’s.

So I went over and talked to Mr. Rose, and I told him that I played a hoedown fiddle. He laughed and said, “Oh, you’re one of them fiddlers.”

I said “I don’t know if I am one of them fiddlers or not. I can play the violin, but I can also play a fiddle.” He said, “I’ll tell what I’m gonna do, I’m gonna try you out, son.”

The bandleader went up to the mike and announced that a young fiddle player was going to sit in. So I played, I forget what — oh yea, “Take Me Back to Tulsa.” I tell you, when I finished, I had that place in an uproar.

The bandleader went up to the mike and announced that a young fiddle player was going to sit in. So I played, I forget what — oh yea, “Take Me Back to Tulsa.” I tell you, when I finished, I had that place in an uproar.

The bandleader was Curly Robinson from Alabama, and Rose told him “Curly, I think we need this young man.”

Rose hired me, and I played with different bands that played there.

Later, Rose started a strip show there, and he had the windows blacked out. He had jazz bands coming there, and one of the guys asked me if I knew anything about playing upright bass. I said “Yeah, I know something about it.” They had a drummer, sax man and a piano player but needed a bass to put more fire to it. So I started playing with the jazz group for the strip shows.

When the band would take a break and another band would come on stage, I’d go across the street to Uncle Billy’s. They had a band in there playing Dixieland, and they was really swinging it out. They had an upright bass player and he knew I wanted to play with them, so he said to come on up and just sit in for a while. So sometimes I would go back and forth between Rose’s and Uncle Billy’s. Some of the other guys would be going back and forth too.

Man, they was hot times then.

So after that slacked off, I started playing up in D.C. and places like that. But the bands would not play the kind of stuff that I had been used to playing; they played that slow country, the old Ernest Tubb style, dragging it all out.

Around here they didn’t pay enough to make a go of it, so I joined the carpenters’ union. There was a lot of building going on. I still would play music on the weekends and do other jobs, so I was able to get by.

Roy Clark, was a pretty good friend of mine, we played music together in those days. And I worked with Jimmy Dean for a while. Jimmy Dean was an accordion player from Texas. He came up here: I think he was in the Air Force, stationed up at Bolling Air Force Base. When he got out, he stayed and he started playing around these joints.

He could be hard to please; sometimes he would get dissatisfied. More than once he would hire Roy Clark and then get dissatisfied and fire him. Later on he would hire him back.

Someone else I played with a few times was Chubby Wise. Me and old Chubby was pretty good friends.

Connie B. Gay had brought Chubby up from Nashville where he was playing with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys. Connie B. Gay was the man who claimed to have brought country music to Washington, D.C., to try to get things going up here.

I played with the Stoneman family, too. Scotty Stoneman was a hell of a fiddle player, but they still didn’t play the kind of stuff that I was used to playing.

I Did OK

I wanted to play that western swing, and I was able to do it.

I stayed with the musicians’ union, and every now and then I would get calls from bands looking for a fiddler. Usually it was some young band looking to go on the road. Most of the time I would tell them I wanted to think about it. Sometimes they would be calling back, but I guess I had enough of that kind of life.

A couple of years ago I made a CD with some local musicians. It’s a pretty good record, I think. It’s called Wild Bill and the Hiccups. I wouldn’t mind doing that again. I still have copies of it for sale.

I still play, of course, and I teach some fiddle, too. I take my fiddle down to the jam sessions they have at the fire hall in Prince Frederick. They like to play a lot of bluegrass and that slow country, which ain’t exactly my style, but it’s alright, I guess. I try to show some of those guys my style of playing jazz and western swing. Some of them catch on to it pretty good.

I still play, of course, and I teach some fiddle, too. I take my fiddle down to the jam sessions they have at the fire hall in Prince Frederick. They like to play a lot of bluegrass and that slow country, which ain’t exactly my style, but it’s alright, I guess. I try to show some of those guys my style of playing jazz and western swing. Some of them catch on to it pretty good.

I’ve had an interesting life as a musician. I played with some well-known people and I enjoyed it. It wasn’t always easy. It could be nerve-wracking, playing in front of thousands of people. You had to be right! But if you could handle it, it was a good job.

I wanted to play that western swing music, and I got in with some guys who showed me and I was able to do it. Looking back, I think I did okay.

to the top

He was a lone Easterner, perhaps the only Marylander, to make a name playing the genre. He traveled and toured, played on the radio and on record as well as before thousands of fans until, eventually, life on the road took its toll and he headed back East.

He was a lone Easterner, perhaps the only Marylander, to make a name playing the genre. He traveled and toured, played on the radio and on record as well as before thousands of fans until, eventually, life on the road took its toll and he headed back East. I had a cousin named Jimmy Stallings. He lived down the road and his father had a farm. He got an old, beat-up Sears S-hole guitar. We got together and we played around the area, just him and me. We’d sit around and play on porches like that. And we got to be pretty good and people would come around and say “Listen to them kids, they sound alright,” you know. I was about 13 and he was about 14 at the time.

I had a cousin named Jimmy Stallings. He lived down the road and his father had a farm. He got an old, beat-up Sears S-hole guitar. We got together and we played around the area, just him and me. We’d sit around and play on porches like that. And we got to be pretty good and people would come around and say “Listen to them kids, they sound alright,” you know. I was about 13 and he was about 14 at the time. I worked with them on weekends for a while, but I wanted a job working every night. They told me “there ain’t no places around here that do that,” but I found a place out in the Texas panhandle, Abilene, and I started playing with a group there. They were playing every night except for Monday, and that’s when I started making my way.

I worked with them on weekends for a while, but I wanted a job working every night. They told me “there ain’t no places around here that do that,” but I found a place out in the Texas panhandle, Abilene, and I started playing with a group there. They were playing every night except for Monday, and that’s when I started making my way. He said, “We don’t hire violin players. We play the fiddle. Very seldom do we ever get a classical violinist.” He was just teasing me. He asked if I had my fiddle and if I wanted to sit in on a couple songs, and I jumped on it.

He said, “We don’t hire violin players. We play the fiddle. Very seldom do we ever get a classical violinist.” He was just teasing me. He asked if I had my fiddle and if I wanted to sit in on a couple songs, and I jumped on it. The bandleader went up to the mike and announced that a young fiddle player was going to sit in. So I played, I forget what — oh yea, “Take Me Back to Tulsa.” I tell you, when I finished, I had that place in an uproar.

The bandleader went up to the mike and announced that a young fiddle player was going to sit in. So I played, I forget what — oh yea, “Take Me Back to Tulsa.” I tell you, when I finished, I had that place in an uproar. I still play, of course, and I teach some fiddle, too. I take my fiddle down to the jam sessions they have at the fire hall in Prince Frederick. They like to play a lot of bluegrass and that slow country, which ain’t exactly my style, but it’s alright, I guess. I try to show some of those guys my style of playing jazz and western swing. Some of them catch on to it pretty good.

I still play, of course, and I teach some fiddle, too. I take my fiddle down to the jam sessions they have at the fire hall in Prince Frederick. They like to play a lot of bluegrass and that slow country, which ain’t exactly my style, but it’s alright, I guess. I try to show some of those guys my style of playing jazz and western swing. Some of them catch on to it pretty good.