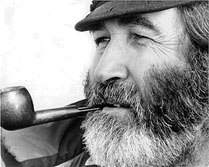

Burton on the Bay:

Standing Up for No-Shoulders

The snake stood up for evil in the garden.

-Robert Frost.

My fellow New Englander didn't go far enough in that line from his poem "The Ax-Helve." Snakes in my opinion stand up for evil anywhere. And I can't say anything much better for anything like them - including eels.

In my younger days, as with most country boys and later young men, nothing frightened me. Nothing, that is, but snakes.

Gradually fear dissipated, although when my Seabee unit shipped out of California for the Pacific, I feared the possibility of encounters with jungle snakes more than I feared Japanese soldiers.

Snakes Spoil a Hunt

I never encountered a snake - we called 'em "no-shoulders" - so confidence was restored. To a point.

Then, on a mountain lion hunt in the West with the late Royden Blunt, I awoke one chilly morning to discover a pair of rattlers practically as sleeping bag mates. The remainder of the hunt I spent more time looking out for snakes than looking for mountain lions.

When spring turkey hunting in South Carolina over the years - and the chase for gobblers in April thereabouts is my favorite shooting sport - my mind was never at ease. Warmer mornings brought out the rattlers.

One day at another plantation where deer abounded, I was assured that chances of rattlers were nil, and I started down a trail with a guide. We hadn't gone 100 yards before he put his boot to a small rattler. Needless to say, concentrating on deer wasn't easy the next two days - even though I wore snake-proof chaps over high boots.

Then there was that time on Hunting Creek in Frederick County.

There I was on the chase of freshwater trout and doing nicely. Suddenly, my eyes caught something unusual on a high bank nearby. Perched on rocks getting some late morning sun was a rattlesnake. For a short time it was sole owner of an expensive Orvis rod and reel. I was gone. A braver companion, Gil Stover, retrieved the rod and reel.

In the late days of the following winter while grouse hunting in the mountains of Western Maryland there came an even greater fright.

It was one of those late winter days when the weather had turned unusually warm, and my companion the late Tom Cofield - then outdoor writer for the old News American - came across a young rattler, which he figured would be great for a daughter's science project.

I objected, but to no avail. The snake went into a sack and was placed in the late game warden Joe Minke's car. Apprehensive, I got back in and we headed for lunch, following which, we re-entered the car and I looked down at the sack. It appeared empty.

I poked it with a night stick lying on the dashboard; sure enough, it was empty. I was the first out of the car. Minke and Cofield searched the car; no snake. It must have slipped out of the car via the floorboard, I was assured. It took some convincing, and eventually I got back in and we proceeded to the afternoon hunt.

I was the first to limit out on grouse. When I returned to the car and opened the door, the snake slithered out by my feet. I grabbed my double barrel 12-gauge, loaded it and by then Cofield approached shouting "No, no" - too late. His daughter had to come up with a better idea for a science project.

Only a Fish Would Eat an Eel

So you get my drift. I'm not much for anything that doesn't have shoulders, which includes eels - though I do have a soft spot for Chessie. If you want me to leave the dining room early, plunk an eel dish on the table.

Curiously, drifting eels for rockfish is among my favorite fishing sports - though I'm not particularly fond of handling them and sometimes wonder why I'd eat anything that would eat an eel.

But an eel is so much bigger and developed than a worm that I feel for it when I drop it overboard to "feed" a rock. If it catches one, I won't use it again; instead I'll reward it by giving it its freedom and use another for the next drift. I feel somewhat distressed when fishing eels for rock in areas where bluefish swim because the latter snack on eel tails - and what's a no-shoulders without a tail?

I'm concerned about eels in another way, also. As commercial fleets become more efficient, they're becoming more popular on the dinner table worldwide. And it takes no rocket scientist to know what that means.

The current issue of National Fisherman - the bible of commercial fishermen and a good read for all interested in the ocean and its fishes - has a two-page spread on eels featuring Chesapeake waterman Fred Maddox of Shelltown, Md.

The sub-headline is ominous. "Foreign markets stimulate demand for American Variety." That tells the story. The lowly, slimy eel that prompts in many the memories of childhood fears of snakes is the subject of an image re-make in the U.S. Elsewhere the eel is already considered a delicacy.

It deserves more respect, says National Fisherman. We get more people to respect the eel, they'll eat more of them, we'll catch more, prices will rise, we'll make more money and so on.

Which prompts the question: What about the eel population? Eels have their own important niche in the scheme of the sea. They are an important food source for many species and determine some fish migrations. How much pressure can they endure? Will they share with cod, shad, herring, even menhaden the potential for disaster if their popularity for table or other fare is enhanced this side of the ocean?

There are signs that eel populations already are hit by fishing pressure. Rising prices are one of them. When eels were considered trash, one who fished eels for rock could buy a dozen for two bucks. Last rockfish season they sold for between $1.25 and $1.50 each.

Once eels were an in-between catch - a means to make a few bucks when not crabbing, clamming, oystering and tending nets. As other species decline or regulations for them stiffen, more attention is paid to eels, which range from the southern tip of Greenland to northeastern South America.

Our American eels live most of their lives in freshwater and estuaries, spawning in the ocean and only in one place: the Sargasso Sea east of the Bahamas and south of Bermuda. The offspring migrate to estuaries, where they will spend the next eight to 24 years before heading back to the Sargasso to spawn. And die.

For ages, the Indians took a few. They had better fare in cod, rock, shad and such, and later so did we. But now, with less of the more attractive alternatives available and those more costly, we're about to improve the image of the eel. Make it more attractive to consumers.

Maybe we can short-circuit the effort and save the eels by reminding would-be consumers of the words of Ambrose Bierce, who in an entry in The Devil's Dictionary of 1906 wrote:

Eels. Edible. adj. good to eat, wholesome to digest, as a worm to a toad, a toad to a snake, a snake to a pig, and a man to a worm.

Maybe that'll turn some would-be eel gourmets off at the pass. Enough said.

| Back to Archives |

VolumeVI Number 5

February 5-11, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |