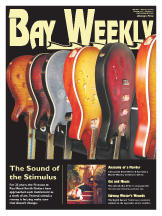

The Sound of Stimulus

For 25 years, the Picassos at Paul Reed Smith Guitars have approached each instrument as a work of art. Federal stimulus money is helping make sure that doesn’t change.

by Simone Gorrindo

“I don’t mess with the payroll. I don’t change where the stairs are,” says Paul Reed Smith, who started Paul Reed Smith Guitars in a garret on Annapolis’ West Street in 1985. “It’s when things aren’t complete that you have to keep working with them.”

You’d think that after 25 years, the third-largest guitar manufacturer in the country might be nearing that point. Not a chance. With a huge factory expansion underway in Stevensville and a new line of acoustic guitars and amplifiers for sale, the next round of changes at PRS is just getting started.

Anyone who works at Paul Reed Smith Guitars starts on the sanding line, above. Stained guitar bodies await final finishing, top. The shop’s daily goal is to turn out 48 guitars.

|

“I’m almost plagued with these things to the point of it being not cool,” says Smith. “I mean, I just can’t stop.”

“I’m almost plagued with these things to the point of it being not cool,” says Smith. “I mean, I just can’t stop.”

Despite PRS’s momentum, the economy has rattled its structure. “The expansion was unfortunate timing,” says spokeswoman Rebecca Eaddy. “We were already deep into planning when the economy tanked.”

In July, PRS made its first layoff in company history: 30 workers. Then government stimulus money came to the rescue, helping PRS maintain, indeed enhance, its cadre of artisans.

At $787 billion, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is so big it’s hard to see. Here’s a small look at how it’s working in Chesapeake Country.

Artists at Work

PRS has come a long way since Smith, an awkward, skinny kid “full of courage and fear,” fashioned electric guitars on his own, making his way backstage at gigs to sell them to guitarists of bands like Heart and Return to Forever. But today’s factory still has the feeling of an old luthier shop, only larger. Under the glare of small, yellow lamps, the employees work hunched over — shaggy hair in their eyes, jeans covered in dust, their fingers rough with work.

Musical discord blares from speakers across the floor. “It’s amazing,” says Christie Woodard, head of human resources. “In one corner, you’ve got country, in another, heavy metal and in another, rap.” It all competes with the whirring of sanders and machines. But the workers appear undisturbed, maybe even inspired by the chaos of noise surrounding them.

Paul Reed Smith Guitars are known for their unique tone, distinctive beauty and precision of craft — qualities that led guitar great Carlos Santana to call Smith’s first creation for him an “accident of God.”

The workers at PRS are an essential part of that tradition. “Some people might call it old-school, but it’s just this: Everyone cares, everyone’s on the same page in terms of quality,” says topcoat manager Rich Hannon.

Sanding — the “proving ground,” Eaddy calls it — is the entry point for everyone who works hands-on with the guitars at PRS. “These guys are the real Picassos of guitar work,” says James Davis, pointing a nicked-up finger at rows of sanders. Davis, who operates the Computer Numeric Control machines that whittle out the guitars’ rough form, started as a sander. He’s worked at PRS for 18 years. Here the contour and shape of the guitar’s body is sculpted, and here PRS president Jack Higginbotham started 25 years ago.

A white board listing the daily and monthly goals for guitar production hangs above the workers. The numbers are ambitious — 912 guitars a month, which breaks down to 48 a day — and the workers’ unwavering focus bodes well for the target. At the bottom of the board, the current average of 44.7 reminds them that they’re still behind.

Conceptually, PRS has always worked on the foundation of collective energy and intelligence

“You get a better result when there’s a feedback loop,” says Smith.

“Paul’s constantly meeting people, getting new ideas from them,” says Eaddy. The notion comes to life in the workshop, where employees pore over their work, arguing with one another about tiny flaws or glitches in the bodies. The guitars are checked at every stage — cutting, gluing, sanding, staining, polishing — so that every worker is accountable. “They can really claim ownership,” Eaddy says.

At the final polishing stages, trained eyes pick these out with precision: “See that little mark right there?” says Hannon, pointing to an imperceptible fleck one of the polishers is rubbing out: “Unacceptable.”

PRS guitars are made of some of the finest wood in the world, the backs of mahogany, the tops of curly or quilted maple. “No piece of quilted maple in the world is the same,” explains Davis, running his finger over a block of maple that has recently come from the heated drying room. Smith calls this wood the “lifeblood” of the guitars.

A Little Money Goes a Long Way

The workers, trained from the ground up, are the lifeblood of the company. “Everyone we hire, we want to keep,” says Christie Woodard, head of human resources at PRS.

Through The American Recovery Act, the fabled guitar maker found the means to keep its remaining workers working full time in these hard times: $33,500 for cross-training in new skills.

From a garrett in Annapolis, Paul Reed Smith, above, has grown his business to the third-largest guitar maker in America. A $33,500 federal grant to cross-train workers has saved jobs at the plant. From a garrett in Annapolis, Paul Reed Smith, above, has grown his business to the third-largest guitar maker in America. A $33,500 federal grant to cross-train workers has saved jobs at the plant.

|

Think of the American Recovery as a river. A big river. From that river, $787 billion flows across America. About $4 billion flows into Maryland, where it’s supposed to create or save up to 66,000 jobs. One of Maryland’s channels for disbursing those life-giving waters is the Governor’s Workforce Investment Board. In each of our counties or regions, boards have been at work for seven years training economically disadvantaged and dislocated workers. In this economy, their resources had gone pretty dry. Then the big river flowed into Maryland.

“I don’t think our proposal would have been approved without the stimulus money this year,” says PRS’s Woodard.

She’s right. “Without federal stimulus money, we would have had to shut down July 1,” explains Dan Mcdermott, who runs the Upper Shore Workforce Development Board where PRS turned for help. “PRS and every contract we’ve negotiated since July 1 was paid with stimulus money.”

The PRS contract provides 50 percent federal reimbursement for the costs of training existing workers.

“It’s cross-training,” Mcdermott explains, “so that if they see increased demand in electric guitars, they can send people to that area, or amplifiers or acoustic guitars. The whole project is to cross-train employees so they can move them throughout the business to respond to demand.”

Early in the new year, First District Congressman Frank Kratovil visited the PRS factory to see the impact of the funding.

“Getting out of this economic drought isn’t just about creating jobs,” he said. “It’s about ensuring that people like the employees of PRS have skills they need to keep their current ones.”

Smith agrees.

“It would have been horrible if it hadn’t happened,” Smith told Bay Weekly. “Imagine laying off 30 people, and the rest losing their fifth day. They got to keep their fifth day. It’s awesome.”

By January, 108 of 235 targeted PRS workers had cross-trained to keep their jobs full time.

![]()

From a garrett in Annapolis, Paul Reed Smith, above, has grown his business to the third-largest guitar maker in America. A $33,500 federal grant to cross-train workers has saved jobs at the plant.

From a garrett in Annapolis, Paul Reed Smith, above, has grown his business to the third-largest guitar maker in America. A $33,500 federal grant to cross-train workers has saved jobs at the plant.