Chesapeake Bay's Independent Newspaper ~ Since 1993

1629 Forest Drive, Annapolis, MD 21403 ~ 410-626-9888

Volume xviii, Issue 8 ~ February 25 - March 3, 2010

Home \\ Correspondence \\ from the Editor \\ Submit a Letter \\ Classifieds \\ Contact Us

Best of the Bay \\ Dining Guide \\ Home & Garden Guide \\ Archives \\ Distribution \\ Advertising![]()

What’s the Use of Black History Month?

If we listen, we’ll hear amazing stories, like Leroy Battle’s

What does February’s designation as Black History month mean about the rest of the year? If Bay Weekly runs our share of black history stories this month, have we done our duty? Is it a newsworthy subject for only one month?

If so, what does that say about the success of integration in our United States?

Those questions were on my mind as I joined a small audience in the National Archives to see an old movie, Wings for This Man: A Salute to the Tuskegee Airmen, and hear the talk of old Airmen and historians.

Produced in 1944 by the Army Air Forces, the 11-minute film about the 994 pilots trained in Tuskegee from 1941 to 1946 is a black-and-white spectacle of tiny airplanes buzzing off to sting the Nazis. As in Tuskegee, the best talents in the nation worked in the war effort. Lord, give me one who can write like that I prayed, hearing the screenwriter’s powerful plain English. The narrator was pretty good, too: a young actor named Ronald Reagan.

Most extraordinary, however, is what Reagan and the screenwriter didn’t say. Wings for This Man isn’t a film about colored soldiers or Negroes; we never hear those words. Instead we hear about how “American boys — students, workingmen, everyday citizens” trained to fly, fight and die.

Acceptance like that happened only in the movies.

That’s what the National Archives speakers and Chesapeake Country Airman Leroy Battle told me.

The Tuskegee Airmen fought over 15,000 combat sorties with skill and bravery, earning 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and destroying 262 German airplanes, 950 railcars and trucks — and one destroyer. But they fought their hardest, longest battle against racism in the land they defended. Scrimmages ranged from everyday insults to mutiny.

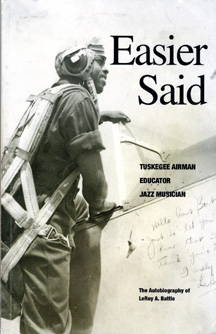

Those are the battle scars and honors Leroy Battle, of Harwood, took from his service as a Tuskegee Airman.

“We had to go through South Carolina,” he told me. “It was August, and hot on the bus. A corporal who only had to salute [for us to pass the base gatehouse] dilly-dallied. One of the cadets called out can you hurry it up, please.

“The corporal called out who said that, came on the bus, took the first cadet and said you come with me. When all of us stood up, he ran to the guardhouse and got a submachine gun. He was going to kill us all.”

A colonel backed up behind the bus defused that bomb, but the Tuskegee cadets lost their leave.

At another gatehouse, Battle had caught a ride with Coleman Young. The future mayor of Detroit was already a lieutenant retraining as an airman. When the guard refused to salute, Young confronted him. “If you don’t salute me, salute this pin,” he said, holding out the insignia on his collar.

“

“![]() That’s how I learned my lesson,” Battle told me. “If you’re right, you stand up to it. You go to the wall.”

That’s how I learned my lesson,” Battle told me. “If you’re right, you stand up to it. You go to the wall.”

So Battle was the 18th arrested when he and 100 other Airmen of the 477th Medium Bombardment Group followed Young in defying a base commander’s order forbidding them entry to the officers’ club. They were at Freeman Field in Indiana, on their way to the war in the Pacific. Their wartime defiance could have ended their service with death.

Battle turned 88 on January 1. He’d been a rising jazz drummer on New York’s 52nd Street, “the jazz street,” when he was drafted, and after his service he returned to music as a teacher, training prize-winning high school bands in Prince George’s County.

“I was naturally a male, but I became a man as a result of the Airmen,” Battle says.

Those stories of black history made up my mind. We’re too busy with the present to look back at history. Black History Month gives us occasion to look back — and examine our consciences about what we’d have done had we been there.

Leroy Battle hasn’t retired from telling the story of the Tuskegee Airmen. His presentation includes the film, Wings for this Man. To engage him as a speaker or buy either of this two books, Easier Said and The Beat Goes On, phone him at home: 410-741-1997.

© COPYRIGHT 2010 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.