Shooting for the Moon

Alphonso ‘Hawk’ Hawkins gathered fresh water by the bucketful as a boy in Calvert County. Today he sits second from the top of Maryland’s Natural Resource Police

by Margaret Tearman

As a boy, Alphonso Hawkins liked to gaze into Calvert’s starry night sky, imagining how bright his own star would shine. But the night sky gave no hint that young Hawk would one day rise to second in charge of the police force that protects Maryland’s natural resources.

True, Hawk — his lifelong nickname — spent much of his youth outdoors, competing on an athletic field when he wasn’t working on a tobacco farm or a construction site. But he never considered himself an outdoorsman.

“My fifth-grade class camping trip at Camp Mohawk, now Kings Landing, was the extent of my camping experience,” Hawkins says.

But there was never a doubt in his mind that he wanted to be a lawman.

“The FBI was my favorite TV show,” Hawkins says. “Going into law enforcement was all I ever wanted.”

Surrounded by a supportive family and community, he never doubted his dream.

Today, as deputy superintendent of the Maryland Natural Resources Police, Hawk guides a uniformed force of more than 250 charged with protecting Maryland’s natural resources.

Making a Man

“We were poor,” Hawkins tells Bay Weekly of his Calvert County childhood. “My mother was a domestic worker, making maybe $6 a day, and my father worked in construction.”

Things were hard enough that Hawkins and his three siblings often lived with family until his parents could afford a home of their own. Even then, it was rough going.

“We didn’t have plumbing until 1966,” says Hawkins, who was born at Johns Hopkins on July 11, 1952. Fresh water meant crossing what is now busy Route 4 to a spring on Sheckells Road.

“It was a job we did every day,” Hawkins says. “Dad never wanted to see a dry water bucket.”

One pair of pants and a shirt had to get him through the week. But Hawkins never felt poor.

“Our parents always provided for us,” he says. “We were never hungry. Our clothes were hand-me-downs, but we had clothes. We always had, not a lot, but we had.”

To earn real money, Hawkins worked on many of Calvert’s old tobacco farms. That hard labor taught him the value of a good job. It also introduced him to his white neighbors. “My community was black,” he says, “and we didn’t socialize with whites.”

In Calvert’s public schools, he stepped into the white world. This was the 1960s, and racial tension was high.

“When I was in seventh grade at all-black Mt. Harmony Junior High, the Board of Education recruited volunteers to attend all-white Calvert Junior High School in Prince Frederick,” the soft-spoken, hard-built Hawk recalls. “Two students volunteered. I was one of them.”

“I saw so much on TV about race relations and riots, I knew I wanted to make a difference. I couldn’t wait.”

With the blessing of his parents, Hawkins started eighth grade in the all-white school.

“That first day was tension-laden, and I was a little scared,” he recalls

Hawk credits a forward-thinking teacher with breaking the racial ice.

“My history teacher, Mr. Lamb, believed in interactive teaching,” Hawk says. “He set up classroom teams with captains. At first, I was the last one chosen for a team. But when the game ended, I was the last one standing. After that, I was the first draft pick.”

Integration had begun. But change was slow.

“In the ninth grade, my bus stop was one of the first, and I got a seat,” says Hawkins. “But when the bus filled up, the black bus driver made me give up my seat to a white student.” He complied without anger.

“Any racism I experienced did not change my mind or my heart about people. It’s not in my DNA. I was taught to love and respect all people, regardless of color. My mother always told me if I’m mistreated by someone, just pray for them.”

Hawk says those groundbreaking years were good overall.

“I think I made a difference in the lives of my classmates,” he says. “I hope I erased preconceptions.”

Making His Mark

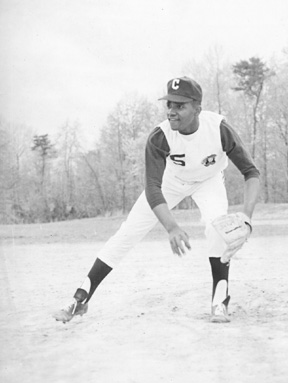

Hawk’s other dream was Major League Baseball.

He was a high school junior when he and his brother tried out for the Baltimore Orioles. To their surprise, they were offered a contract for the team’s farm club. But their mother objected. She wanted her boys in school.

Dutifully, Hawk stayed in school, content to wait for the sports scholarship he knew would come. It did. Graduating from Calvert High School in 1970, he went on to study and pitch at Maryland State College — now University of Maryland Eastern Shore — on a full baseball scholarship.

He was scouted, but when the time came — after he had earned his degree in business — he joined the Prince George’s police, where he stayed for 21 years. He sampled every aspect of the job — undercover on the street to the press office. Promotions came in succession: sergeant, lieutenant, captain, major. By 1995, he was interim chief. When the chief’s job was offered, he declined; the position required county residency, and Hawk didn’t want to leave Calvert County. He retired from the force, at the rank of lieutenant colonel, in 1997.

His retirement lasted just three days. He began his second career as a captain in the Maryland Park Police. His next step, three years ago, was to deputy superintendent of Natural Resources Police.

These officers’ mean streets are trails and waterways, but that doesn’t make the job easy — or always safe.

“Not everyone sees us as officers willing to assist, to preserve and protect,” Hawk says. “While enforcing boating laws, officers encounter boaters under the influence. In the woods they are in harm’s way because hunters are armed, but we don’t know what they’re thinking.

“It’s a danger putting on that uniform, walking out that door in today’s society. Daily, I think about making sure our men and women go home safely.”

Closing the Circle

Hawk and his wife Rochell — a retired health administrator — live in Huntingtown, just a few miles from his childhood home. But Calvert County has changed since he was a boy. It’s a good thing he no longer has to cross Route 4 to get drinking water.

“So many more people and a lot more traffic,” Hawkins says. “But there is also more diversity, which is good.”

Hawk’s life has been, in his words, “blessed.” He knows his success is the result of hard work, but he does not underestimate the support and encouragement he received along the way.

“I want my legacy to be as a mentor,” he says. “Encouraging and motivating people is what good leaders do. I’ve seen people ascend the ladder of success and rank, and I think I’ve been instrumental in their success, helping them to believe in themselves.”

He calls mentoring young people his Number One job.

“Our children are our future,” he says, “and they are our present.”

“Let’s not forget the present,” he advises young people. “Be mindful you will someday be an adult. Don’t think being a teenager is an excuse. You need to learn to work with people, develop people skills. Be diligent about your behavior and character and attitude. Think about your career now. Think about coming to the table with the cleanest record.”

Even at the summit of his present, Hawk continues to think about his own future. When he finally turns in his badge, it won’t mean retirement.

“I plan to seek political office,” he confides.

His plans for his future draw on his past. A man who has some experience in changing people’s perceptions, he wants, he says “to bring a different perspective to politics. Too often people look at politicians as being dishonest. I’d like to show that politics is about helping people, not about self-aggrandizing.”

Hawk still stands in Calvert’s night to gaze at the stars.

“Once upon a time I was given some good advice: Always shoot for the moon. Even if you don’t make it, you will at least be among the stars.”

![]()