Singin’ the Blue Crab Blues ~ redux

Singin’ the Blue Crab Blues ~ redux

A decade later, everybody keeps singin’ that same, sad song

by J. Alex Knoll

Spring sends a wave of life through the water. Slowly the Chesapeake warms, releasing many of its children from hibernation.

Buried in the muck, blue crabs stretch their limbs and test the water. Soon all but the weakest and the oldest will emerge from their long sleep, hungry to eat whatever their claws can grasp.

Above water, hunger also rises, as crab lovers ready their mallets and stock up on Old Bay. Crabbers paint their boats and ready their gear.

But for many Chesapeake watermen, 1992’s crab season never began, and they worry that 1993 might be no better.

“It was one of the slowest years I’ve had,” said waterman Lou Doetsch Jr., of Grasonville. Doetsch, a bearded man who smiles as amiably and talks as freely as an old friend, has been crabbing since 1962. Last summer he supplemented his income repairing motors.

Just how bad was 1992’s crab season?

A little more than 30.25 million pounds of crabs were landed, according to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

Update: 1993 was better, with a harvest of 55 million pounds, but worse was still to come. Annual hauls dropped to 20.2 million pounds in 2000. So bleak was the picture that Maryland and Virginia agreed to reduce their harvests by 15 percent in 2003, hoping to boost the reproducing population.

1992’s millions of pounds of crabs might sound like a lot, and if that many crabs were dumped in your lap you’d be scurrying.

However, from 1983-1993, the annual commercial catch had averaged 48 million pounds, according to DNR.

Update: Lower still was Maryland’s total crab harvest in 2002: 23.8 million pounds, compared to 22.7 million in 2001 and 20.2 million in 2002.

Update: Lower still was Maryland’s total crab harvest in 2002: 23.8 million pounds, compared to 22.7 million in 2001 and 20.2 million in 2002.

As does any business, crabbing has good years and bad.

“If you look at the commercial records, it’s happened before,” said Harley Speir, project manager of DNR’s tidewater fisheries program. But, he said, “we want to make sure it’s a one-year thing.”

There’s good reason to play it safe. DNR valued 1992’s crab harvest at more than $20 million. Add in related businesses — such as crab houses, picking and packing plants, bait suppliers, pot manufacturers — and Maryland’s crab industry nears $150 million, said Noreen L. Eberly, seafood marketing specialist for the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

“Its the biggest industry in the Bay,” she said.

Update: In 2001 — the most recent figures — the value of Maryland’s crab industry had risen to $243 million. “The poundage is a lot less, but as the harvest shrinks, the value increases,” says Eberly, who continues to promote Maryland seafood.

William J. Goldsborough, senior fisheries scientist for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, agreed that crabs are vital to the Bay. “If crabs drop off for an extended period of time, you’ll see a big effect,” Goldsborough said. In a worst-case scenario, there could be “people losing their boats and houses in some communities.”

Update: So vital that watermen helped elect Gov. Robert Ehrlich, who promised in his campaign to ease the regulations put in force by former Gov. Parris Glendening to reach that 15 percent reduction.

Ehrlich eventually compromised on a legal-catch-size formula that would still reduce the harvest by 15 percent in 2003. Five inches tip to tip is legal for hard crabs until July 15, when the minimum jumps back to five and a quarter inches. The size limits on soft crabs are similarly eased.

“It’s not going to kill the crabber like it would have done,” said Larry Simns, president of the Maryland Watermen’s Association. “The governor did a good job for watermen without harming the crab resource, which is a fine line to walk.”

Will crabbers take it on the chin again in 1993?

Will there be crabs to keep the picking houses at optimum production?

Will there be enough high-quality crabs to keep people filling the crab houses?

No Crystal Ball

No Crystal Ball

Nobody knows for sure, but everybody’s guessing.

“I think it’ll be better in ’93. There were a lot of peelers so there’s the possibility of big crabs this year, ” Doetsch predicted, hopefully.

Update: Anybody who’s predicted crabs has always been made a fool of,” said Simns, who expects the 2003 season to be “normal, not bad or outstanding.”

A relatively mild winter could also boost the crab population. The warmer the weather, the more crabs that are likely to survive until spring, said Speir of DNR. We’ve “not observed any large-scale die-off of crabs over the winter, and no excess mortality is at least a good sign.”

Brian Rothschild, a professor at University of Maryland’s Chesapeake Biological Laboratory in Solomons, based his 1993 optimism on Virginia’s winter dredge surveys of hibernating crabs. “They’re the same crabs in the winter dredge as Maryland’s summer catch. If you don’t see many crabs in the winter dredge season there probably won’t be many in the summer,” he said. The surveys predicted last summer’s decline; this year “there seems to be an increase.”

Update: As everybody knows, winter 2003 was anything but mild. How the crabs have been affected won’t be known until some time in May, when 2003’s winter dredge survey is analyzed. “I hope what we see this year is an abundance, but I cannot say that yet with certainty,” says Phil Jones, DNR’s director of fisheries resource management.

Dredger Tommy Leggett wasn’t cheered by the ’93 winter dredge story: “The winter crab dredge hit a low last season,” he said, “and in my opinion it’s worse this season.”

Despite a master’s degree in marine science, Leggett calls himself a “self-taught waterman.” He is also the western branch president of the Virginia Working Watermen’s Association, based in Gloucester County.

Crabs follow a seven-to-12 year population cycle with “peaks of abundance and valleys of depression,” Leggett said. “I would say that we’re at the bottom and scientist’s would agree. We should see the crab population start rising.”

But other prognosticators fear more than a low in the cycle. Some blame toxics in the Bay. Others cite poor weather conditions. Some accuse rockfish of eating too many crabs. Still others worry that both increased crabbing and Virginia dredging threaten the fishery.

The most likely explanation combines many causes.

The Pollution Premise

The Pollution Premise

For decades the Chesapeake has been the rug under which we’ve swept our dirt. Unlike poor natural conditions, which change eventually, pollution does not go away.

“All that stuff coming out of those water purification plants and the factories — it’s gotta’ be killing something,” said Henry Bush, a Miller’s Island waterman. The loss of aquatic sea grasses in the Chesapeake is just one example of the damage caused by pollution, Bush said.

Update: In 2003, Governor Ehrlich made improving the treatment of sewage a keystone of his environmental program. In a year of tight money, the House of Delegates followed Ehrlich’s lead, voting to spend $11.5 million on improving plants that treat wastewater.

Herb Powell, general manager of Blue Heron Seafood Co. in Somerset County, blamed pollution in the Bay as a “major factor” in 1992’s poor crab season. Nor is the state focusing on the source of the problem, Powell complained: “I don’t believe they’re going after the big polluters, the big factories up in Baltimore, just the little polluters.”

However Mike Sullivan of Maryland’s Department of the Environment didn’t buy that argument.

“We’ve made tremendous progress ratcheting down on the number of pollutants from industrial sources,” he said.

What adds up to trouble for crabs and other marine life is high levels of nitrogen and phosphorous in the Bay, Sullivan said.

Combined, the two make the water nutrient-rich, encouraging algae blooms that block light and deplete oxygen, thus suffocating other marine life, he explained.

Update: In 2003, nitrogen and phosphorous are still labeled as the culprits in Bay pollution. Under the headline “Bay officials agree to slash nutrient inputs almost 50 percent from ’85 levels,” Bay Journal reported last month that reaching that goal would yield “dramatic expansions in beds of underwater grasses, much clear water, fewer algae blooms and a greatly reduced oxygen-depleted ‘dead zone.’”

Costs would be just as impressive. Over a billion dollars a year is the pessimistic estimate for Bay states to limit nitrogen entering the Bay from all sources to 175 million pounds a year and phosphorus to 12.8 million pounds.

Most phosphorous and nitrogen comes from fertilizer run-off, Sullivan said. But about 15 to 20 percent of the nitrogen entering the Bay is air-borne, from sources such as factory and power plant chimneys, automobiles and even fireplaces.

“Most people don’t link clean air to the Bay’s health,” Sullivan said. It’s harder to monitor, but we believe it’ll lead to benefits for natural resources.”

Survival of the Fittest

Crabs face natural threats and predators at every stage of their lives. Winds, currents, air and water temperatures all affect the crab population.

Fish and mammals prey on crabs — and so do other crabs. “There’s a fair amount of cannibalism among crabs. It appears to be a natural part of the crab cycle,” said scientist-dredger Leggett.

Then again, rockfish could be the culprit. Rockfish, or striped bass, recovered from endangerment, thanks to a strict five-year catch moratorium. Some saw their return and crabs’ decline as more than coincidental.

Update: Rockfish, which are back in abundance, still get a bad rap in some quarters. “There are a lot of little crabs but a lot of fish to eat them up,” said Waterman’s Association president Simns, looking forward to the 2003 crab season.

L.K. Woodland will tell you that by 1993 he’d been in the crab industry for more than 50 years — “too long,” as he put it. Woodland began as a waterman and now owns the Dorchester Crab Co., a picking house on the Eastern Shore. “Rockfish don’t only eat soft crabs,” he said. “They eat small hard crabs, too.” Woodland saw the proof firsthand last fall. “While filleting rockfish, we opened up 17,” he said. “The smallest amount of whole crabs we found was at least five. The most was 47. That’s daily.”

Update: Mr. Woodland has added another decade to his long career in the crab industry, and Dorchester Crab Co. will be picking again in 2003, as soon as watermen start catching. The season, which opened April 1, gets off to a slow start as Bay waters hold winter’s chill. April accounts for only one or two percent of the annual crab harvest.

DNR’s Harley Speir wouldn’t argue. “Striped bass are pretty opportunistic,” he said. “They do eat crabs, no doubt about it.” But, he added, crabs are a minor part of their diet.

Speir explained that the commercial catch records for rockfish and crabs over a 20-year period show “no relationship between the abundance of striped bass ... and the crab population.”

That, however, is nothing new. Crabs have always been a lower link in the food chain, which remains consistent from year to year. Weather conditions are less static.

“We had a very cold summer in 1992,” Pete Jenson said. “The average water temperature was much cooler.” Jenson, the director of DNR’s fisheries division of tidewater administration, suspects the low temperature had something to do with last season’s low crab catch.

Mike Oesterling, a Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences commercial fisheries specialist, discounted the cold summer of ’92’s effect since there were also few crabs in Virginia’s warmer waters. If only the temperature was to blame, Oesterling said, “we should have had crabs coming out of our ears, and that didn’t happen.”

Too Many Pots Spoil the Catch

By 1993, Scott Smith, a soft-spoken waterman who listens to National Public Radio while working, had crabbed out of Town Point marina for more than 20 years. He worries that too many watermen have been channeled to crabs with the decline of other fisheries.

“Crabs need to have a good oyster and clam industry,” Smith explained. “You can’t have the thousands of watermen all working in one industry.”

When a fishery dries up, Smith said, the waterman has little choice but to switch to another fishery. “He’s not going to go out and become a budget analyst.”

Update: Yet Smith left crabbing in 2000 to commute to Washington, D.C., where he is now a web-page designer.

In 1993, DNR licensed a record 15,858 overall crabbers.

Update: Since 1993, crab license categories have changed. In 2002, 2,600 people reported catching blue crabs commercially.

The increase in crabbers has another effect, said Lou Doetsch Jr. of the crabber’s early ’90s plight. “Years ago, I could get by with 150 pots, catch 10 bushels of crabs. Now I have to run around 300 to get 10 bushels,” he said.

DNR disagreed. “There is no evidence right now that we are over-fishing crabs to the point that reproduction is threatened,” said that agency’s Speir. If not immediate danger, however, Speir acknowledged a point of diminishing returns:

“Obviously if you have a number of fish or crabs in one place and you have a lot of people coming out and taking a lot of them over the week, and [the fish or crabs] can’t replenish themselves, there won’t be as many next week for people to catch.”

To Dredge or Not to Dredge

To Dredge or Not to Dredge

If you want a fight, tell a Virginia waterman that dredging threatens the crab industry.

Many Maryland watermen have long been picking that fight.

If Virginia dredging halted “for one year, we’d have more crabs than we’d know what to do with,” claimed Miller’s Island crabber Henry Bush.

Illegal in Maryland, dredging is a significant part of Virginia’s crab industry. Come winter, as the water cools, female crabs return to the mouth of the Bay. They burrow into the mud to insulate themselves from the water’s chill. Many hibernating crabs never see spring. When Virginia’s regular crab season ends in December, the dredge season begins. It lasts until the end of March, when the regular season starts once again.

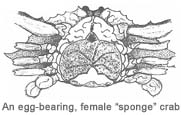

Dredging scrapes up crabs indiscriminately, Town Point crabber Smith said, and “is detrimental because it tends to pick up the egg-bearing females.” These females would otherwise lay eggs in the spring, he said.

No evidence proves that dredging is bad for the overall crab population, countered Oesterling, from the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences. “We haven’t seen any effect on the resource in 40 years,” he said.

Speir, Oesterling’s commercial fisheries counterpart at DNR, also defended Virginia dredging. “I think that for the Virginia dredge industry to be singled out is wrong,” he said. Maryland watermen harvest non-egg-bearing females during the crab season and are “contributing to mortality.”

Nor did Virginian Tommy Leggett blame dredging for the dip in the mid-1990s’ crab population. Dredged females would be caught anyway come spring, Leggett argued. What’s wrong, he said, are Maryland’s hypocritical dredging regulations. Dredged crabs from Virginia may be sold in Maryland, and Virginia “allows Maryland crabbers to come down here and dredge.”

Still, many Maryland crabbers believe dredging should be stopped.

“You’d find a lot of people, even here in Virginia, who’d go along with a dredging ban, but I’m a fence-sitter,” Leggett said. “I think it would be a mistake to jeopardize what little fishery we have left without more data. It’s an excellent time to get that.”

Give Crabs a Helping Hand

What can be done to guarantee that crab harvests won’t continue to slide? Natural population trends and weather conditions are beyond our control.

Still, everyone can help.

The Bay’s continued health and cleanliness ensure that when natural conditions allow, crabs can flourish.

We can help reduce the amount of pollutants entering the Bay. How? Bring garbage back to shore. Maintain your septic system or petition your water treatment facility to reduce the amount of waste it releases into the Bay.

Keep gasoline-powered engines well tuned, drive less and cut your energy consumption to reduce the amount of airborne nitrogen reaching the Bay.

As consumers, we have clout on what crabs reach the market. “Ignore the junk,” Speir suggested. “Demand high-quality crabs.” Selectivity will drive down demand for immature crabs, which will grow and reproduce, benefitting everyone in the long run.

As consumers, we have clout on what crabs reach the market. “Ignore the junk,” Speir suggested. “Demand high-quality crabs.” Selectivity will drive down demand for immature crabs, which will grow and reproduce, benefitting everyone in the long run.

Earlier in1993, DNR proposed to do more, restricting the days and the hours that commercial watermen could crab. This proposal met such stiff opposition from watermen that it was quickly withdrawn.

A blue crab advisory panel — made up of scientists, watermen, and members of DNR — considered new regulations on crabbing. Pete Jensen, a member of this panel, said that catch limits, gear limits and entry restrictions are possible.

Update: Pete Jensen — fired as DNR’s deputy director of fisheries in Glendening’s administration for too ardently championing the cause of commerical fishermen — has been rehired by Ehrlich in 2003 as deputy director of the entire department. Commercial watermen rejoiced at his return, said Watermen’s Association president Simns.

Such talk of increased regulations worries many crabbers.

“There’s enough restrictions on us as it is,” Grasonville’s Doetsch complained. “Don’t limit what I can do. If I can’t make it now, why limit me to the amount of gear I can put out or limit my catch?”

But restrictions may be necessary to guarantee the blue crab’s place in the Bay and the economy, Speir countered.

Update: Restrictions, which have been since put in place on crabbing hours and season length as well as the size of legal crabs, are as unpopular as ever.

“We’re conservationists not preservationists,” Speir said in ’93. “We want the blue crab to be used 100 years from now.”

Popular Throughout the Food Chain

Survival of the fittest rules nature, and crabs face their share of natural hazards before growing to a size where they interest people.

Female crabs spawning at the mouth of the Bay lay millions of microscopic eggs. The mortality rate is enormous. Only a fraction — just how many is anyone’s guess — survive to hatch during the spring. Beginning as pinpoint-sized larvae, the crabs rely on favorable winds and tides to carry them into the relative safety of the Chesapeake. Otherwise they are swept out to sea where their odds of survival are minimal. Jellyfish, small fish and other plankton-eaters prey upon the defenseless larvae at this stage and as they grow into juvenile crabs, which are eaten by larger predators, such as rockfish, herons and racoons.

Crabs need warm water and plenty of food to thrive. As they grow, crabs become too big for their own britches, so to speak, and shed their shells. Until a new, larger shell forms over the next few days, these ‘soft-shells’ are completely helpless — and recognizedly tasty. Anything that can get hold of a crab at this stage will gladly eat it.

With the approach of winter, surviving crabs head south and burrow into the mud. The harsher the winter, the fewer survivors come spring. Those that make it soon grow to legal size.

Update: In 2003, legal size is five to five and a quarter inches across from point to point, depending on the time of year they’re caught.

As the water warms, crabs shed more frequently, growing from one-quarter to one-third larger each shed.

Any crab that reaches the minimum legal size has defied the odds of nature. Now it must contend with us.

to the top