|

|

|

Folklore informant Ricky Shelor cradles his first-ever decoy.

photo by Russ Barnes

|

Informants Talk* Bay Country History

by Russ Barnes

“I found out one thing,” says Ricky Shelor about growing up in Lusby. “You can’t sit down inside a bucket and hoist yourself up outa’ the well.”

Ricky, 42, artist and former waterman, is an “informant.” No, he does not work for the FBI or CIA. He does duty for folklore researchers using fragile oral history to document Bay Country’s living folklore. Speaking the wisdom of the community in its own tongue — as he’s just done in remarking the danger of isolation — is part of that duty.

Shelor grew up on a farm in Lusby, became a waterman and, because of a back injury — “probably from jumping out of haylofts as a kid” — left the water two years ago. He began building model Chesapeake boats and other artifacts. Next, he turned to painting, applying acrylic paint to many different surfaces. The subjects are all Bay Country: water scenes, buildings standing today and buildings remaining only in memory.

In between telling stories about his early life in Calvert County, Shelor tenderly cradles the first decoy he ever made. Nearby sits another decoy, sculpted by him and his son with an ax from a block of pine. In the skills and traditions of Bay Country, Shelor is a wealthy man.

Informants of Shelor’s caliber are treasured by folklore researchers for their extraordinary story-telling abilities.

“Something is going on inside my head like a rolodex,” says Shelor referring to his ability to bring up on his inner screen vivid memories of Bay Country life from the database of his fertile brain.

Coin of the Realm

Shelor’s ability is good as gold to folklorists Michael and Carrie Kline. They’re the partners — in life as well as work — tapped by Historic St. Mary’s City and St. Mary’s College of Maryland to document folklife in five counties of Southern Maryland: Anne Arundel, Calvert, Charles, Prince George’s and St. Mary’s. Shelor is their first volunteer informant since last November’s launch of the Southern Maryland Folk Life Documentation Project. The job of the Klines’ “spoken history project” is to produce audio and CD interviews from the recollections of regional volunteers like Shelor.

For 30 years, the Klines have studied and chronicled the history and culture of Appalachia in several West Virginia regions, producing a series of audio-taped interviews with as many as 200 informants. Their audio productions have aired on National Public Radio, the BBC and many radio stations.

The three-year Southern Maryland Folk Life Documentation Project is funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, which is also supporting studies of the Piedmont, Eastern Shore and Western Maryland. Its grants are passed down through the Maryland Arts Council and the Maryland Historic Trust to St. Mary’s College of Maryland and Historic St. Mary’s City.

Folklorists like the Klines mine the murky zone between old and new, dramatizing social changes as communities leave traditional folkways for modern times. The transition is not solely an American phenomenon but a global one. The change that comes as traditional societies move from old ways to new ways of life often creates anxiety — as the current of world events keeps reminding us.

While U.S. localities like Southern Maryland may not represent the same scope or degree of change as Afghanistan, Saudia Arabia, China or Africa, these American localities do share with their global brethren a similar ambiguous relationship to modernity. Need it be said that folklorists address issues that oftimes light the fuse of global conflagration?

|

Folklorists Carrie and Michael Kline produce audio and CD interviews from the recollections of regional volunteers for their spoken history project.

photo courtesy of Historic St. Mary’s City

|

Where the Real People Are

Fissionable as their material is, it’s not in the halls of power that Michael and Carrie Kline seek their informants.

The authorities and experts — government officials, big businesses, corporate media, big labor unions — have ready tellers for their stories. They’re not what the Klines are looking for.

“Too often, authentic voices in the community are never heard,” says Carrie Kline, the writer and promoter of the partnership. To which her audio-producer husband adds, “We interview people who’ve been subsumed by the authorities. We want to encourage expression, the voices of real people who know what they are talking about.”

Often what they hear challenges the status quo, as informants voice their own or their community’s opinions on, say, race or labor unions.

It’s the laundromats and doughnut huts of Southern Maryland the Klines are mining.

“We go to the laundromat or the shopping center, keeping our ears open so that we might discover an imaginative and informative speaker,” says Michael Kline. “There are informal conversation areas — social spaces — around some of these public places. You might see a klatch of these people along a sidewalk in a shopping center.”

“I always see a group like this when I go to Radio Shack,” Kline says. “The group stands around the same place, but people move in and out. We figure the participants are exchanging community news. There may be gold there if you can tap into one of these informal conversations.”

In Lusby, says Ricky Shelor, that spot is a big oak tree.

You can see such a tree in the painting he calls “Duke’s Store,” which Shelor says comes from imagination but is probably based on his early memories of Lusby.

Right here, Shelor says, is where the Oak Tree Boys [gathered] in the evenings during the summer. Kids used to run around here in the store yard. Play, throw rocks at each other, play tag.

“I remember this area right here, my grandfather’s brother, which would be my great uncle. And they’d sit around and just talk about what they had done that day, and what this one done five years before that, and still mad at this one because of 10 years ago.

“His wife’d be sitting there with the door open, with her head leaning out the door leaning on it, and that is how she would set for about three hours. They all just talk about daily stuff.”

Of course you don’t just muscle into a group like Shelor’s Oak Tree Boys. “It takes sensitivity and respect to make it into the group as a listener. You have to listen and wait, ” Michael Kline advises.

Which leads to the second article of the Klines’ credo: “To get the true story, whether it’s about shucking oysters or making music or butchering hogs, it’s important to allow the person telling the story to be the expert.”

Expert is what Ricky Shelor clearly is on the distance you had to go to find entertainment in rural Chesapeake Country.

You hear talk of people like going down Drum Point drag racing and stuff, but back when I was growing up everybody just didn’t take off. Wasn’t like no big thing to get out. There wasn’t nowhere to go once you got out. There was, you know, nothing anywheres.

My grandmother used to go to Solomons to the laundromat. I think it was on Mondays and Thursdays. And that was kind of sometimes nice to ride down there. Still wasn’t nothing to do once you got down there! You just talked to older people, lot of charter boat captains there.

You learn a lot from listening to them, like the way they fish and stuff. Then after I got older I started … I learned how to trap just by my cousin telling me how to trap. I hitchhiked to Solomons one day. He gave me a dozen muskrat traps. Then after school I trapped the swamp up by St. Leonard.

I started out with a dozen traps and ended up with about 60 dozen muskrat traps. I used to fox trap. To me, I mean, that was just what all kids done back then was, you know, work on the farm or trap and hunt. Then for entertainment they’d sit around at that old tree at Pardoe’s store in the summertime. And that was entertainment back then.

Like Shelor, the Klines have made an occupation out of the “lot you learn from listening.”

“Some schools of thought would have you start out with research, so you know your subject before you start,” Carrie Kline says. “But we work hard to start out with no preconceptions. We make a record of community speech with no third-person commentary or intervention.”

The Klines want their stories unmediated because they’re fresher that way. But the vitality of uncensored speech and thought is only part of reason they go to the people: the butcher, the baker, the fireman, the policeman, the hairdresser, the fast-food worker, the farmer, the waterman. One more reason is that it takes a story to make a community, for story-telling speaks meaning into life and life into meaning. The converse is also true for, as Carrie Kline says, “It takes a village to tell a story.”

Yet another reason is that the Klines believe intuitively the dictum of the ultimate folklorist, Carl Jung: “The reason for evil in the world is that people are not able to tell their stories.”

|

The big oak tree beside Duke’s Place, a Calvert County Store from the past, was the gathering place for southern Calvert Countians.

reproduced courtesy of Ricky Shelor, ©2001, acryllic paint on canvas.

|

Chesapeake Folkways

The Klines have been researching Southern Maryland folklife since November of last year. In that time, they’ve begun to learn how Bay Country’s folk roots compare with those of other regions.

The biggest similarity the Klines see among most regions of the United States is “overwhelming change.”

“Outside corporate interests have moved in,” says Michael Kline. “Modern roads and telecommunications have been introduced, and television has opened up mass marketing.” All these factors change the way people work, shop, eat, learn and interact.

But Southern Maryland is distinctive, as well. Bay Country history goes back to the early 1600s, while many communities only 150 miles west began only 200 years ago. Thus, Kline explains, “The region has an extraordinary, deeply rooted sense of history.”

Nor has Chesapeake Country ever been so isolated as, say, some regions in Appalachia. “Even in the days of poor roads, Chesapeake Bay steamboats provided cheap and convenient transportation to take people out of the confines of their region,” Kline says. “You were able walk down to the wharf, flag a boat, and be inside museums in Baltimore within hours.”

Nor are are Chesapeake natives, in Kline’s words, “ashamed of its past — as some regions seem to be.” One reason, he believes, is that people of Southern Maryland experienced a minimum of corporate exploitation as compared to West Virginia communities that felt the degradation of logging and coal interests. As hard as life has been for some in Southern Maryland, independence has given their lives dignity, whence springs pride.

And while racial relations have not always been savory in the region, the presence of a long-term community of African American citizens in Southern Maryland has resulted in, what Kline calls “two races; one lifestyle.”

That’s a conclusion Kline sniffed out, in part, from Ricky Shelor’s memories:

When I guess I was about 24, I was over at Oxford oystering with Romus Gant and Sylvester Philips. And Romus Gant, he was a great, big, old black man, and he said, ‘Hey cracker, how old are you?’

And I said, ‘Um, 24.’

He said, ‘You’re just a young snot yet,’ or something like that.

And then Sylvester, he broke in and says something about killing hogs, because his father and them used to kill hogs with my grandfather.

When I was little that was about the onliest time I seen black people was when it was time to kill hogs. Because they’d be bringing their hogs by and help, you know, kill whatever was there. And then they’d go get theirs and kill theirs. And after that the blacks would take their hogs and go home. You know, might see them on the road or something but as far as talking to them, that’s that … or maybe in a tobacco bed you might see a few of them. But a lot of them that I grew up and knew from farming, most of them’s done died out.

As by them being black you don’t really know them as much; you don’t see them as often as you would the white farmers. But you still learn from them, though.

|

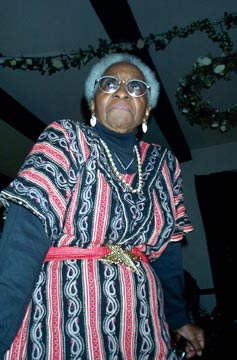

Folklore informant Mary Louise Webb.

photo by Russ Barnes

|

As Real on the Other Side

Where Ricky Shelor was the outsider, Mary Louise Webb, now of Waldorf, was the insider.

Webb, who is African American, grew up on a 200-acre Charles County tobacco, corn and hay farm near Bryantown. Her family was forced to sell the farm in 1943 when she was 18. The farm was broken up into 13 lots and sold separately — a victim of modernity. That necessity catapulted her into a new way of life.

She became a practical nurse at D.C. General Hospital. But she’s kept her traditions alive by volunteering for such organizations as the 4H Club and the Maryland Cooperative Extension service.

“Those kids get so much by visiting a farm,” Webb says. “It empowers them. It gives them freedom. They get to go where they want to go, when they want to go. They are free on the farm to do their own projects. They become constructive. It gratifies me to see that happen.”

Louise Webb may soon have more opportunity to host children at a farm, this time her farm. There’s a chance she may be able to buy back six acres of the farm she grew up on. “Of course, we’ll grow berries and corn,” she says. “But we’ll also set up a petting zoo for the children.”

Reweaving the Tapestry

You’ve been reading “soundbite” of informants’ memories. The Klines record these bites verbatim for the record. But when they go to tell a story, they reorganize memories by topic and add sound effects — including regional music — to evoke the scene. The object is to create a master story with the building blocks of many individual stories woven together into a meaningful pattern. Post-produced, the stories are then printed onto audio cassette or CD, packaged and distributed for entertainment, edification and research.

“People,” Carrie Kline says, “are the experts on their own lives. We just weave their stories together into a quilt of stories.”

It’s no accident the Klines work with the spoken word and with people from traditional rural cultures who are intelligent speakers and listeners but who may have, in some ways, difficulty with what Michael Kline calls “establishment modes” of communications: reading and writing.

Kline, who grew up in Washington, D.C., was unable to read until midlife because of a severe learning disability. Yet he is a graduate of St. Alban’s School and earned a PhD in public folklore from Boston University.

Carrie, who hold a master’s degree in American studies from State University of New York/Buffalo manages with the team’s written communications as well as producing their audio programs.

As we talk, Michael Kline looks up from the audio-editing equipment in his office in Farthings Ordinary, close by St. Mary’s River, to reflect on the work to which he has dedicated his life.

“The question that always comes up in this work is ‘Who owns history?’” He knows the answer or he wouldn’t ask the question. Whoever speaks it, owns it. And “owning history” provides a usable, high self-estimation to any group lucky enough to have someone able and willing to speak its history.

More affluent segments of society own printing presses and television stations. Other segments, like the one Ricky Shelor and Mary Louise Webb speak for, talk with each other at informal conversation areas. Sometimes they get to speak with folklorists like the Klines.

If you keep a sharp lookout around Bay Country for informal conversation areas, you might join a conversation in progress. Or you may be discovered there by folklorists; the Klines say they are actively looking for folklore informants in Bay Country. And you just might gain more information than you expected by standing around the parking lot or laundromat.

You might pick up some good counsel on how to survive the crush of new against old — what Michael Kline calls “overwhelming change” faced by traditional cultures from the corporate “Wal-Mart-ing of America.” Each side alone has its limitation. On the one hand, modernity challenges traditional life values. On the other hand, modernity challenges poverty, bigotry and ignorance.

What is so impressive about a person like Ricky Shelor is not merely the formidable rolodex in his head. The folklorists and their informants may give us navigational charts to help steer our courses between the two poles.

See Shelor’s paintings and models at such places as the spring opening of the Piney Point Lighthouse, the St. Clement’s Island festival of the Blessing of the Fleet every October and year-round at the Seagull Cove Gift Shop in Solomons Island.

Learn the folklorist’s craft from the Klines’ summer workshop in folklore field techniques for professionals and amateurs this June 16-29 at St. Mary’s College. While you’re there, check in on the progress of another project of the Klines, the Historic St. Mary’s City Audio Walking Tour, a self-guided audio tour of 40 sites scheduled for summer completion.

Learn more? 240/895-4989 • www.folktalk.org.

To hear an audio clip of Ricky Shelor speaking about his experiences of Calvert County, click on the link below!

{This clip appears on bayweekly.com courtesy of: The Oak Tree Boys. (c) 2002 The Maryland Folk Life Project, taken from an interview by Carrie Kline with engineering by Michael Kline, Southern Maryland Folk Life Project. Editing interns: Meghan O'Gwin and Lucy Peterkin.}

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|