| In a Misty Cove, Anti-Sprawl History Made

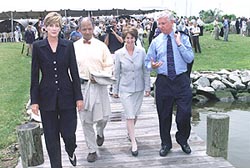

The Chesapeake 2000 Agreement, an anti-sprawl pledge, brought together EPA Administrator Carol Browner, Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, Maryland Lt. Gov. Kathleen Kennedy Townsend and Gov. Parris Glendening, among others.

We are the Barclay

Eco-band Eco-band

We don’t throw things in the garbage can

We turn them into instruments

To play recycling music.

So sang the students from the Barclay School in Baltimore, among the several hundred people who turned out on a rainy morning in Southern Anne Arundel County last week for an event that may be recalled as a benchmark nationally in the battle to slow sprawl.

On this day, behind a dais bedecked with black-eyed Susans and in front of ducks gamboling in the waters off Herrington Harbour South, leaders of Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia agreed to a regional conservation plan that would reduce the rate of Chesapeake Country development.

The anti-sprawl pledge was part of the Chesapeake 2000 Agreement, an agreement that also has many anti-pollution features and renews commitments to the 17-year-old Chesapeake Bay Program. But the anti-sprawl portion was a new feature, one that made news across America because it marked the first occasion that states have joined forces to combat the unwise development that is diminishing the quality of life for many people.

“Voters along the Bay have said unambiguously that quality of life matters, that the Bay must be saved,” Gov. Parris Glendening told the crowd. “It is exciting that we’re not only doing some good things but being a model for other areas.”

Glendening observed that planners have come from as far away as Sweden, Brazil and Panama to learn from Maryland’s programs to protect Chesapeake Bay. And nodding to the youthful entertainers from the Barclay School, who made their music with the discarded cans and bottles they collected, Glendening noted that the new agreement can help to restore the Bay for the enjoyment of generations to come.

In the anti-sprawl component of the plan, the leaders agreed to reduce by 30 percent the rate of development along Chesapeake Bay by 2012. To accomplish that, each state and the District of Columbia promised to develop separate plans.

The leaders also said they will join forces to preserve over one million acres of land by 2010, which would bring to about 20 percent the land that is protected permanently in the watershed. There is no legal mechanism to force the states to abide by the agreement. But signing the document assures that each jurisdiction will be pressured by the public, the press and one another to live up to the bargain.

Carol Browner, administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, said the agreement “gives the public a way of holding us all accountable.”

Virginia, which has been slow over the years to adopt preservation and anti-pollution initiatives, did not agree to the plan until goals were scaled back. Virginia Gov. James Gilmore did not show up for the ceremony, and neither did Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge.

Virginia’s natural resources director, John Paul Woodley Jr., said that further studies due in 2001 to help states meet the goals will be “essential to the success of this initiative.” He seemed to be implying that Virginia will be watching closely to make certain that it is not pushed in directions it doesn’t want to go.

The new program had several important features overshadowed by the sprawl provisions:

Expand public access points to the Chesapeake Bay by 30 percent by 2010;

Increase designated water trails by 500 miles by 2005;

Recommit to agreements to curb Bay-choking nitrogen pollution by 40 percent over the next several years after failing to reach that goal by 2000;

Increase native oysters by tenfold by 2010, which will require more oyster seeding and expansion of protected oysters;

Step up monitoring of invasive species, like nutria and mute swans;

Recommit to restoring 114,000 acres of Bay grasses, roughly the amount of the 1930s;

Restore 25,000 acres of wetlands to achieve a policy of “no-net loss” of the marshy areas that provide habitat for aquatic creatures and filter pollutants that run off from the land.

Tall Ships Sail Out to Sea Again

I must down to the seas again,

to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star

to steer her by … to steer her by …

Led by Pride of Baltimore II and flanked by the high-flying water plumes of a bright red fireboat, the tall ships sailed out to sea, leaving goodwill in their wake. Left behind were the hundreds of thousands of admirers who stayed the course, through sun and heat and rain, to climb aboard or simply watch vessels of old glide by.

For five days, Baltimore’s harbor brimmed with barques and bugeyes, schooners and skipjacks. With light winds under sail and clearing skies overhead, crews representing 16 countries, including the United States, scaled intricate rigging for the best view in town as they waved goodbye to a harbor town that was a lot like the ships themselves: a showcase for the present and a reminder of the past.

Today, the maritime tradition is a vibrant, growth industry as reproductions of sailing vessels in countless countries train modern-day seafarers and educate all who share a passion for the sea. Recreated with current materials and the latest technology, replicas of vessels that plied the world’s waters hundreds of years ago — clipper ships, schooners with three and four massive masts, two-masted brigs, three-masted barques and brigantines — now breathe new life into an ancient tradition.

In the final parade of sail, history made its passage. From the deck of Pride II, an authentic recreation of the 1812 Baltimore Clipper, a cannon boomed announcing the departure of each tall ship.

How tall is tall? Behind Pride, the Chilean four-masted schooner Esmeralda, the tallest of the tall, reached for the stars at 165 feet and stretched horizontally to 371 feet. Falling in line next came Danmark, the 253 foot long steel s hip, fully rigged to a towering 148 feet against the Baltimore skyline. hip, fully rigged to a towering 148 feet against the Baltimore skyline.

Size isn’t everything, of course. Small new vessels — including Bay Weekly’s host, the 76-foot wood schooner Imagine of Annapolis, and the skipjack Nathan of Dorchester, built in Cambridge, Maryland in 1994 by local volunteers working with master shipwright Bobby Ruark — were woven into the queue of grander ships of state.

Maryland was well represented in OpSail 2000, and what the homegrown fleet lacked in size, it made up for in variety of Baycraft — all but two the real thing, not replicas. Filling out that fleet were the 1889 oyster dredging bugeye Edna E. Lockwood, a National Historic Landmark, and the younger Kathryn M. Lee, a Chesapeake Bay schooner built in 1932, the only schooner in Maryland’s oyster fleet. Reaching back in history is the Maryland Dove, a full-scale operating replica of the ship that carried supplies for the 1634 expedition from England to our virgin Chesapeake shores.

No matter the height nor length of the craft, a commonality is the connectedness you get in sharing space under the sun and stars, learning the lesson that interdependence is the law of sailing as of life.

Goodwill ambassadors all, these tall ships and their training and volunteer crews ply the seas for months at a time, visiting around the world. Baltimore’s Pride II has just returned from 11 months of touring Asian ports. That’s a big dose of connectedness. Viewing the ships from the deck of the Imagine, Jay Astle, an Annapolitan and Naval Academy graduate, said he had once gone out to sea for six months. How long did that seem? “Long,” he said.

Reminders are all around that we have one foot firmly in the 21st century though our dreams are rooted in the past. Our smaller world is much changed since the days of steering by stars and sextant. Dot-com companies now fill office space along gleaming new marine centers, like Canton along Baltimore’s northeastern waterfront, even as the old Domino Sugar plant stacks billow with white, sweet-scented steam. From the throngs of crowds waving good-bye, cell phones jingle-jangled as new ships of old sailed under Key Bridge and headed for the open Bay.

Not since the QEII came steaming up the Bay a decade ago has there been so much excitement afloat to stir our hearts.

Way Downstream …

In Baltimore, Nancy Foster, a marine biologist who established the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s office in Annapolis, died on June 27, of a brain tumor. She was widely known, and this spring NOAA’s Florida Keys Environmental Center in Key West was named in her honor …

In Georgia, the bald eagle is back thanks to restoration efforts. Unfortunately, they’re dying from a malady called avian vacuolar myelinopathy. In an editorial last week, the Augusta Chronicle observed: “It would be a cruel irony if the endangered species act succeeded in preserving the big birds from extinction, only to have Mother Nature wipe them out” …

In South Africa, 40 percent of the world’s penguins have been endangered by a huge oil spill in the waters off Cape Town. In the biggest bird rescue in history, wildlife specialists were racing to evacuate 20,000 birds coated in oil …

In Montana, Yellowstone supporters are irked by the park’s decision to place the name of corporate sponsors next to its Web-cam photos of the Old Faithful geyser, in exchange for $5,000. The Greater Yellowstone Coalition’s Joe Catton called it the electronic equivalent of putting up a billboard next to Old Faithful...

Our Creature Feature comes from Colorado, where authorities say that larcenous black bears are doing much more these days than snatching picnic baskets. In Boulder Canyon, a black bear smashed a kitchen window in a cabin and made off with a cake and an entire bowl of apples.

But that was bearly enough to eat, judging by another clue left behind: The freezer door was wide open.

Copyright 2000

Bay Weekly

|