|

Our Ailing Bay Takes a Turn for the Worse in 2003

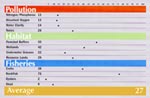

Here’s the bad news: Most anyplace else in the Bay, the smooth-talking, red-headed leader of the Chesapeake’s best heeled advocacy group would have popped up not only wet, cold and embarrassed but also smelling like skunk cabbage. For College Creek — where Baker reported on the state of the Bay in the year 2003 — is about as good as it gets. With an old bulkhead yanked out, banks eased into a gradual slope and native grasses replanted, the shoreline there is looking like its old self — before humans girded it for our good rather than the good of the Bay. Projects like College Creek’s made shoreline restoration one of the few bright spots amidst a lineup of blights on the Bay. On 13 indicators that Chesapeake Bay Foundation scientists use to measure the health of its habitat and fisheries and the severity of its pollution, only one reached the sustainable ideal. Thus, pronounced Baker, “The Bay is still dying — despite 20 years of work by federal and state governments.” Twenty years ago, Bay states, the District of Columbia and an alphabet of federal agencies joined in an unmatched cooperative effort to save the Bay from a rising tide of degradation. In 1983, nobody thought living up to the Chesapeake Bay Agreement would be easy. But everybody expected that by now, we’d have turned that tide. Instead, it’s getting worse — which says something about our efforts as well as about the Bay. “One hundred is the historic ideal Captain John Smith would have seen when he sailed up the Bay 400 years ago,” said Baker, explaining the index, which the Foundation devised six years ago to measure Bay health.

We could, but Baker doesn’t linger there. Instead, he used this inauspicious 20-year anniversary to lob a little blame, to rally the troops and to jump-start the failing effort. “We’ll never reach 100 percent, but 70 seems possible,” he predicted — though not tomorrow. At 70, we’d have saved the Bay. Today, only one indicator — rockfish — has climbed that high. Their score of 75 is due at least in part to human intervention, for in the mid 1980s all rockfishing was banned for five years. Only then, without humans as predators, the Bay’s signature fish rebounded. Baker doesn’t predict that we’ll reach so high for all 13 indicators until 2050. But within our lifetimes — indeed, within fewer years than we’ve already been laboring — Baker thinks we can do better. “By 2010, we can reach 40,” he said — but it will be a stretch. Today, only two of the Foundation’s 13 indicators have risen above 40: forested buffers at 55 and wetlands at 42. By 2020, he hopes we can reach 50. And now he’s going to tell us how. The Bay’s ill health has many causes, but one big one we have the know-how to change: nitrogen. Nitrogen is a naturally occurring element that makes up four-fifths of the volume of Earth’s atmosphere. But in human hands it’s also a fertilizer and waste product, and in that guise nitrogen runoff is killing the Bay.

In the short term — that’s 2010 — 40 million pounds of that load could be stopped by better wastewater treatment. One thing we’ve learned since the original Chesapeake Bay Agreement is how to treat our sewage — which watershed-wide is processed by 300 treatment plants that together release 1.5 million gallons of treated wastewater into the Bay. Cutting back this release of nitrogen-heavy waste is a technique called biological nutrient reduction, and we’ve been getting better and better at it since scientist Clifford Randall of Virginia Tech laid the foundation back in the 1980s. The principle is that if you loose a mess of bacteria on your treatment ponds, under the right circumstances they’ll consume that Bay-killing nitrogen, releasing it as a harmless gas. About half the volume of wasewater processed in the watershed is cleansed by biological nutrient reduction to cut that bad old nitrogen down to about eight parts per million. The technology has since advanced to where nitrogen can be cut to three to five parts per million. But only 10 treatment plants in the whole watershed have upgraded to that standard. That’s in part because state-of-the-art biological nutrient reduction is not cheap. Maryland estimates $5 to $20 per household according to Baker. Multiply that range by Maryland’s 1,980,859 households, and you’re talking big money in one state alone. To transform all those other sewage treatment plants, Baker said, government must make nitrogen removal legally mandatory. To move government, the new administrator of the EPA, former Utah governor Michael Leavitt, would have to “exercise his authority to force states to enforce the Clean Water Act.” To persuade President George W. Bush to share costs for the upgrades, Baker said the whole Bay Executive Committee — Leavitt plus D.C. Mayor Anthony Williams and the governors of Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia — should go calling on the White House. But — and here, said Baker, is the rub — government is the weak link in Bay restoration. “The politics of postponement is killing the Bay,” he charged. “The region’s governments … are putting off till next year important steps that should be made today.” Aye, there’s the rub. — SOM Tables Turned

Ernst took the Foundation to task in his book Chesapeake Bay Blues. Now, the radical professor says the Foundation is cleaning up its act. “Chesapeake Bay Foundation hasn’t changed what they do, but they’ve increased the volume — which is nice but not enough,” Ernst told Bay Weekly.  On the plus side, Ernst gives the mighty Foundation credit for “a good job” in advertising this summer’s Dead Zone and having “the guts” to criticize the overseer of the Bay restoration effort, the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program. Also earning his praise is Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s annual State of the Bay report. On the plus side, Ernst gives the mighty Foundation credit for “a good job” in advertising this summer’s Dead Zone and having “the guts” to criticize the overseer of the Bay restoration effort, the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program. Also earning his praise is Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s annual State of the Bay report.“They’re wonderful at understanding what’s wrong and needs to be done, but…” says Ernst, “they don’t seem to understand why political action isn’t happening.” What the Foundation hasn’t done, by Ernst’s reckoning is “address their organizational structure, which severely limits their ability to be policially influential. They continue to hide behind the tax status they’ve chosen, which limits them from fully engaging in the political process.” How would Professor Ernst grade the Foundation? “I’d give them a C-, and that’s an improvement from a flat F,” said the self-styled “easy grader.” —SOM Growing St. Leonard A community with a past tries for a future Can a crossroads village surrounded by a sprawl of housing developments grow into a thriving community? As Dr. Seuss almost said, “If such a thing could be, it certainly should be.”

Bay Weekly sat in at their November 10 meeting to see where their plans headed. Earth Journal ~ Between Seasons

In Annapolis, the Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network last week announced four new Bay Gateways — one of them the 3,000-acre Parkers Creek Watershed Nature Preserve in Calvert County. Also named were the Patapsco Valley State Park; the B&A Trail; and the Great Bridge Lock Park in Virginia. That brings to 127 the number of parks, refuges, ports, museums and trails in the Gateways Network, which is aimed at giving people a roadmap to better enjoy the Chesapeake… In Virginia, the Potomac River is setting a record for futility this oyster season. “This is truly historic — the fact that there is zero harvest,” Potomac River Fisheries Commission head Kirby Carpenter told the Fredericksburg Freelance-Star one month into a six-month season. Severe oxygen problems along with disease and overharvesting made for the grim report… |

© COPYRIGHT 2003 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Last updated November 13, 2003 @ 2:28am.