|

When air — and water — chill and daylight fades, Chesapeake Country’s clock returns to oyster time. We’re talking eating time.

Bad news about the Bay’s oyster has a year-round season nowadays. Many of our surviving oysters grow in protected sanctuaries where it’s hoped solutions will arise to save the species. With other oysters trying to grow in saltier southern waters you might as well eat them up before they’re gobbled by the diseases that are proving the fittest in this war of survival. (Those diseases, by the way, don’t pass up along the food chain to people). A few smart farmers are figuring how to grow oysters for market, but lots of the oysters we’ll eat this season are harvested in other waters, from Louisiana and Texas to New York.

Along the Chesapeake, oyster lovers may not know where their next oyster is coming from, but they’re eating what they can get with undiminished fervor. So you don’t have to be watching the calendar for the telltale R month — missing from May through August — to know when oyster time arrives. You can tell by the proliferation of oyster affairs.

No sooner have oysters come into legal season in Maryland than the tiny Southern Anne Arundel community of Holland Point celebrates with its annual oyster and bull roast, which was October 5 this year. Pretty soon communities, churches and firehouses up and down the Bay are shucking and patting, and oyster lovers are slurping and stuffing.

If you haven’t been to an oyster feast, you can find out what you’ve been missing on November 8 at the Deale Volunteer Fire Department oyster feast [New Bay Times Vol. 1, No. 15, Nov. 4, 1993]. There, in an atmosphere of shirt-sleeve camaraderie, 33 bushels of oysters are served raw on the half shell and 28 more gallons steamed, fried and puffed. From 1-5pm, for about $23, you can eat all the oysters you can hold in memory of the biggest appetite of all — Deale’s late Tommy ‘Muskrat’ Greene — certified by the Guinness Book of World Records back when it approved of feats of gluttony.

It’s places like this, where eaters abound and shuckers show their skill, that you also catch a glimpse of what oysters meant to Chesapeake Country from the water up. Oysters were the infrastructure on which the Bay depended, filtering its water and nurturing dozens of communities in the Bay chain of being. Whatever civilization lived on Bay shores feasted on oysters, which spawned both commerce and art.

Now it’s our turn, and the feast continues. If you love an oyster — or if you wonder just what could be done to make such a creature edible — tour with us the Chesapeake culinary culture the oyster built.

Cooking for the King

Churches, neighborhood associations and fire departments show you how God meant an oyster to be fried. Each one’s a little different; the Deale standard is twice “patted” with breading, dipped in egg and milk and deep-fried in hot oil. You’ll find no nouvelle oyster cuisine at such affairs, but who needs innovation when tradition tastes so good?

The St. Mary’s County Oyster Festival and National Oyster Cookoff is a feast of a different species. Here, oyster cookery breaks with tradition in favor of innovation.

“We’re looking for something a little different,” says Noreen Eberly of how she and her committee of past champions sort through some hundred entries for the dozen in the annual cook-off sponsored by the seafood marketing division of the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

|

photo by M.L. Faunce

King Oyster, Rotary president Jay Heisley, presides over this year’s first prize-winning cooks: from left Jack Campbell, Dorrie Mednick, grand-prize-winner Jackie Horridge and Marty Hyson. |

Judge-pleasing recipes of a different stripe are what the 12 finalists from eight states including Maryland aimed for at this year’s 24th annual National Oyster Cookoff October 18. The cookoff is a highlight of a two-day festival that can earn as much as $50,000 for the sponsoring Rotary Club of St. Mary’s County. Today the oyster is king, personified by the rotary’s past president, who this year is Jay Heisley. To feed the hungry oyster lovers who thronged this year’s festival, more than 200 bushels and about that many gallons — harvested as far away as Delaware and North Carolina this year — were shucked, scalded and fried.

Festival-goers that fine October day were led by smell to the cook-off in St. Mary’s Fairground Building 16. There, on unfamiliar stoves in front of a hungry oyster-loving audience, finalists recreated concoctions conceived in imagination and first (sometimes over and over again) tried on their families at home.

They cooked in four categories — hors d’oeuvres, main dishes, soups and stews, and outdoor cookery and salads — and they cooked fresh-shucked Maryland oysters.

All the way from Clackamas, Oregon, Jack Campbell pronounced the Maryland oysters “delicate” and better tasting than the large Pacific varieties — all Asian imports grown locally these days — common to the West Coast.

Campbell’s hors d’oeuvre, Oyster Scones with Onion Marmalade, didn’t stray far from his Scottish roots. “With a name like Campbell, you have to be a bit Scottish,” he said, as he concocted his marmalade of sweet Maui onions sautéed with sugar, red wine, vinegar, black currant liqueur, dark rum and pineapple juice. The marmalade is dolloped as a finishing touch onto scones baked with a topping of crisp bacon, an oyster and a slice of Anjou pear, with a dollop of the onion marmalade.

That innovation justified Campbell’s confidence in “the marriage of seafood and fruit,” winning him first place in his category with a $300 prize.

For an appetizer just as original, Robert Vining of Metarie, Louisiana, set a broiled Maryland oyster atop home-grown fried green tomatoes and finished it with blue cheese. A self-described “frustrated chef” who’s an insurance man by day, Vining has entered the national cookoff eight times, qualifying four. He says he “goes to bed at night dreaming of food and how to prepare it.”

As with Vining, innovation is nothing new to the finalists in the main dish category of this year’s cookoff: all three were previous Grand prize winners, an honor that rewards a recipe with $1,000. The first place winner, Marylander Dorrie Mednick from Towson, dreamed up Oyster Galettes with Polenta after a six-month stay in Italy. Like Vining and Campbell, she set her oyster on a throne. Hers was a crisp round of polenta, which is the Italian version of corn-meal mush, flavored with cheese and rosemary and spread with deviled ham.

In another category, soups and stews, 2002 Grand Prize-winner Marty Hyson took first place for his Roasted Chestnut Oyster Stew. He was also first in the hearts of fairgoers, winning the People’s Choice Award. Hyson, from Baltimore, looks for good combinations and easy preparation. This year, he liked “the idea of the nutty flavor of the chestnut” and wanted to create a recipe “that everybody could make.” A consummate watcher of the Food Network, the popular amateur chef wowed judges last year with another of his innovations: Champagne Roasted Oysters with Lemon Butter and Crushed Pistachios, served with flutes of — what else? — champagne. Of course everybody knows oysters go hand in glove with champagne.

But this year oysters went best of all in a simple salad. In Green Goddess Oyster and Artichoke Salad, Jackie Horridge of Nashville, Tennessee, dipped Maryland oysters in egg whites; dredged them in Japanese bread crumbs (called panko) with Parmesan cheese; she then sautéed them to a perfect crisp in olive oil, leaving the oysters moist. They adorned baby field greens and an artichoke bottom dressed with Horridge’s own green goddess dressing.

A green goddess dressing she sampled at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco sparked her imagination, and that powerful memory drizzled over the crisp oysters moved judges to award Horridge not just first place in her category but also the grand prize.

Submit your recipes by August 1, 2004, to Oyster Cook-off, P.O. Box 653, Attention: DEDC, Leonardtown, MD 20650.

Order cookbooks of prize-winning recipes at the same address: $4 for 2003; $6 for ring-bound multi-year collection.

|

Jackie Horridge’s Green Goddess Oyster and Artichoke Salad

|

24 Maryland oysters, shucked

4 cups baby field greens

1 cup grated raw carrot

4 cooked fresh artichokes

11/2 cups panko, or dry fine bread crumbs

1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

2 egg whites, lightly beaten

1–2 cups olive oil

1 recipe Green Goddess dressing (below)

Combine field greens and carrots and divide over 4 salad plates. Remove leaves and chokes of artichokes; discard chokes and save leaves for another use. Place 4 artichoke bottoms on the salad plates. Combine panko, Parmesan cheese and pepper; set aside. Dip the oysters in the egg whites and then dredge in panko mixture. Sauté oysters in hot oil until golden; do in batches, adding more oil as needed. Drain on paper towels. Arrange 6 oysters on each artichoke bottom and spoon about

2 1/4 cup dressing over them. Pass remaining dressing to use as desired.

Green Goddess dressing:

1 clove minced garlic

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon dry mustard

1/8 teaspoon pepper

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

2 tablespoons anchovy paste

1 cup mayonnaise

1/2 cup sour cream

2 tablespoons tarragon wine vinegar

3 tablespoons chopped chives

1/3 cup chopped parsley

1/3 cup chopped fresh spinach leaves

Combine all in blender; blend until smooth. Age, covered, in refrigerator at least 24 hours.

|

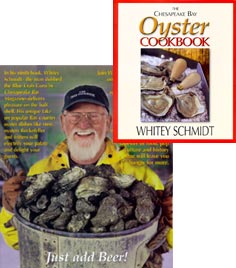

The Bay’s New Oyster Cookbook

“We write poems about oysters; we venerate the watermen who harvest oysters. We hold oyster roasts and oyster festivals that can draw tens of thousands of devotees in a single week-end.”

Thus Bay foodways historian Whitey Schmidt explains why, in his ninth book, he’s turned from crabs to oysters. Thus Bay foodways historian Whitey Schmidt explains why, in his ninth book, he’s turned from crabs to oysters.

Whitey’s brand-new book, The Chesapeake Bay Oyster Cookbook, pays homage to both the eating of the oyster and its culture. Each of his 210 recipes shares its page with an image. With full-page illustrations as frontispieces for each of the 10 chapters and a couple in the introduction, you can tour oyster history, from the 19th century through the 21st, while hunting up a recipe. To keep your appetite whetted, Whitey’s friend Vince Lupo, a professional photographer, contributes a signature of eight color photos of what the recipes amount to.

Recipes and images have been gathered over three decades, as Whitey traveled hundreds of thousands of miles in quest of Maryland’s distinctive cuisine. That’s how his odyssey looks now, nine books in perspective. It began less loftily as a Bay-loving guy’s search for good times.

Back in the early 1980s, Whitey made himself a promise to eat crabs in every place they were steamed and served, from Virginia Beach to Havre de Grace, including both shores of the Bay, tributaries and big cities. That labor led, in 1985, to his first book, The Official Crab Eater’s Guide. Whitey has stayed true to the pleasure principle ever since, paying for his good times by spinning them into guidebooks — Eastern and Western Shores in his two-volume Bay Tripper in the mid-1990s — and cookbooks.

He labors for love, as he confesses in one of the chatty notes that caption his illustrations: “Who’s in a hurry to retire from writing oyster cookbooks?”

His cookbook, in turn, packs you up on a journey that you should not expect to be predictable. Chapters start with culinary themes and double back to cultural and geographic ones. Nor will you always get what’s promised. Crisfield is where Whitey, formerly of Rose Haven in Southern Anne Arundel County, now makes his home. His Chapter 7, “The Town the Oyster Built” promises to be a “History of Crisfield, Maryland.” But the promise is kept only by some of its illustrations and the neat local titles of its recipes, like “Peggy Neck Oysters in a Biscuit.”

“ Peggy Neck Oysters” is a simple enough little recipe. Halve and hollow a good biscuit; butter and season with your favorite seafood seasoning. Pop on an oyster, sprinkle with paprika and broil till edges curl — which is the standard test of any oyster’s doneness. Whitey tops it with a second biscuit half; I’d serve it open, which would about transform it into another recipe Whitey calls Oysters-in-a-Biscuit. Peggy Neck Oysters” is a simple enough little recipe. Halve and hollow a good biscuit; butter and season with your favorite seafood seasoning. Pop on an oyster, sprinkle with paprika and broil till edges curl — which is the standard test of any oyster’s doneness. Whitey tops it with a second biscuit half; I’d serve it open, which would about transform it into another recipe Whitey calls Oysters-in-a-Biscuit.

Does the first come from Peggy Neck? Possibly. Will I eat one someday soon? Certainly.

You’ll value Whitey Schmidt’s Chesapeake Bay Oyster Cookbook for its reverent and playful love of oysters and good eating rather than for its strict history.

Among its contributions:

At least 50 ways to eat an oyster, raw and cooked, on the half shell. Oyster Cocktail for a Crowd calls for 600 oysters in shells. I’d rather not shuck that many, even following Whitey’s tips for shucking. But I’ll certainly eat six, which is the standard number ordained by oyster plates. I’d rather eat a dozen.

For cooked oysters served on what Whitey calls Neptune’s china, I like Lower Marlboro Oysters with Roasted Garlic, which is a little like seasoning your oyster stew with garlic and serving it in individual, shell-cup servings. Essentially, you spice up a shucked oyster with a clove of roasted garlic, add a spoon of hot cream thinned with oyster liquid and top with a chunk of garlic butter.

Garlic is one of the favorite companion’s of Schmidt’s oyster cookery. Every autumn he plants it, and by early summer he harvests a crop of the pungent bulbs. But this autumn he’s cooking up his recipes with oysters harvested farther afield. Even Crisfield, the town that oysters built, is importing oysters from other states to shuck locally.

Among these five or six dozen recipes on the half shell are 20 — indeed, a whole chapter’s worth — on oysters Rockefeller, including a dip that skips the half shell.

The basic Rockefeller ingredient is a chopped green; spinach has become traditional, but experts say the original was scallion tops. Whitey’s recipes branch out to arugula, turnip greens and watercress. The standard hint of licorice can come from using fennel as the green, its seeds or the liqueurs anisette or pernod. Sauté the greens with spices that usually include garlic, shallots, scallions or onions. Vary the seasoning with herbs or anchovy paste. Heighten the piquancy with lemon or hot pepper, whether sauce or flakes. Consider adding bread crumbs or dry, grated Italian cheese. Moisten with oyster liquor, butter, mayonnaise or even cream cheese.

Plump a nice spoonful on a shucked, plump oyster in the deep half of its shell. Top, perhaps, with a chunk of bacon. Broil.

Even richer than Rockefeller is SeaQuest Broiled Oyster with Crab. Here, the sauté is mostly green onions and bread crumbs with a touch of parsley. The kicker is the lump crab sprinkled over the top of the shell-broiled oyster.

A whole chapter on oyster stews, including bisques, chowders, gumbos, jambalaya and even a beer soup. (I’ve tried a beer soup; it was 30 years ago. My family still won’t let me forget.)

Oyster stew at its simplest is oysters and their liquor simmered — never boiled — in milk or cream and lightly seasoned, usually with paprika or seafood spice for a nice touch of color. It’s a lily easily gilded, whether with butter — Church Supper Oyster Stew adds two pounds of butter to three gallons of oysters and four gallons of milk; onions, celery and potatoes; other veggies — spinach, corn, mushrooms, pimento, artichoke hearts; and cheese — even brie. Oyster stew at its simplest is oysters and their liquor simmered — never boiled — in milk or cream and lightly seasoned, usually with paprika or seafood spice for a nice touch of color. It’s a lily easily gilded, whether with butter — Church Supper Oyster Stew adds two pounds of butter to three gallons of oysters and four gallons of milk; onions, celery and potatoes; other veggies — spinach, corn, mushrooms, pimento, artichoke hearts; and cheese — even brie.

A chapter on oyster pies. As Whitey says, Oh my! Among these 21 recipes are five basic types: 1) true pies within crusts; 2) pies crusted with biscuits or English muffins; 3) quiches or single-crust pies filled with custard of eggs and cheese; 4) pies crusted with crumbs, spinach or even crabcakes; 5) crepes and topped muffins.

You’ve got to be careful with a pie; the oysters tend to get lost. Which gives a certain advantage to a true savory oyster pie. Variations abound, but they all start with your best pie crust and proceed to more-or-less simple creamed oysters supplemented with onions (often sautéed with bacon), potatoes, maybe celery and mushrooms, maybe peas and carrots. Season with one of Whitey’s recipes or imagination.

Whatever else you take from The Chesapeake Bay Oyster Cookbook, take Whitey’s advice that the best way to eat or cook an oyster is with fun and friends. “Personally,” he writes in the introduction, “I spend countless hours, standing around the Crab Lab (my Crisfield kitchen) with friends, popping oysters, cracking beers and whipping up old recipes — and some brand new ones — while we slurp oysters and talk about everything from wine to women.”

The Chesapeake Bay Oyster Cookbook, $29.95, at book and Bay-flavor stores throughout Chesapeake Country; or from the author: 888/876-3767.

to the top

Hard Times Indeed

Crassostrea virginica, the oyster responsible for all this, has fallen on hard times. In a race with the microscopic oyster predators that may yet eat the Bay’s last native oyster, only 53,000 bushels, an all-time low, were harvested last year.

Fewer still are likely be harvested by next March, when Maryland oyster season ends.

“The all-time record low used to be 80,0000 bushels in 1984,” says Chris Judy, who is the man on oysters at Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “This year’s harvest is expected to be pretty much half of last year’s. The bottom line is quite terrible: a disaster actually. And when you lose so many oysters this, of course, has economic and ecological impact.” “The all-time record low used to be 80,0000 bushels in 1984,” says Chris Judy, who is the man on oysters at Maryland Department of Natural Resources. “This year’s harvest is expected to be pretty much half of last year’s. The bottom line is quite terrible: a disaster actually. And when you lose so many oysters this, of course, has economic and ecological impact.”

Tom Connor, who works with the department’s Oyster Restoration Program, explains how scraping the bottom of the basket hits watermen. “The Maryland oyster industry is virtually extinct,” he said. In three or four years the number of commercial watermen licensed to oyster has dropped from over 2,000 to 160.

Where are the oysters we’re eating coming from? Most oysters shucked in Maryland processing plants are imported from the Gulf states. Maryland’s remaining oysters are likely to be sold in the shell for the raw market.

The only ray of hope Connor sees in this “dismal picture” is the Asian oyster Ariakensis.

“We’re at the point now where what we need is an oyster that can survive the diseases,” he says, referring to MSX and dermo. “The oyster is such a keystone to the Bay. While we would love to see the oyster recover, we need an oyster survivor, and a non-native oyster may be that oyster.”

According to Connor, Gov. Robert Ehrlich has “recognized that we are in a crisis situation and made it the highest priority in our department to get the oysters back in shape.”

Restoration of native oysters will continue in areas such as the Chester and Choptank rivers where disease is not as significant.

— M.L. Faunce

to the top

|

|