Bay Life

Singing the Chesapeake

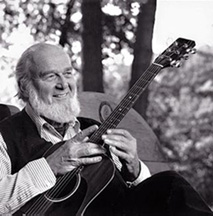

John Denver Award-Winning Folk Musician Tom Wisner

by Kent Mountford • photos by David Harp

‘For a guy parading as a singer-songwriter in the Chesapeake boonies for the past 35 years, getting the John Denver award is like getting an Oscar from God!”

‘For a guy parading as a singer-songwriter in the Chesapeake boonies for the past 35 years, getting the John Denver award is like getting an Oscar from God!”

So said Chesapeake folk artist Tom Wisner on receiving the 2002 World Folk Music Association’s John Denver Award. He liked, for one thing, the connection to John Denver, for he was a fan. “I’m glad I had the chance, while he was still alive, to thank him for what he did for folk music,” said Wisner of his honor’s namesake artist, who died in 1997 when the small plane he was piloting plunged into California’s Monterey Bay.

Tom also liked the insight it stirred in him.

At the award presentation in January, 2003, at the Birchmere music hall in Alexandria, Wisner performed with some of the greats of the genre. “I learned something about myself on those two nights of performance,” he said, “something I wish I’d really known about myself years ago.

“I watched some of those people at the top of the mark in this business build energy on that stage. I do better in the woods; better standing in a stream with the kids around me, letting the time and place speak to me. Then the music of it comes out of me.”

Big as America

Tom Wisner’s a big man, a presence when he enters a room, with a speaking voice that booms even as his singing voice, when he’s deep inside his music. There’s a Santa Clause twinkle behind his glasses, and behind his snowy beard is the cherubic face of perpetual childhood.

The kid came out to play at a Christmas gathering to celebrate the marriage of Chesapeake writer Tom Horton. Finding the early-teenage son of a colleague timidly trying out his brace of hand-drums, Tom gave an instant lesson in boldness, his big hands flying over the stretched goat and calfskins like lightning and filling the room with sounds of high and low timbre.

Tom’s a father himself, with five children from a marriage long ago. His son, Mark sang with him on some albums, worked aboard a skipjack in the Bay and today fishes commercially in Vancouver, B.C. In a crushing blow to Tom, his beautiful daughter was killed many years ago in an accident born of youthful exuberance.

Tom is also a man in whom the American land and its folk have a lot invested.

His mother Katie’s side — the Babers — seem to have had the deepest roots, with lots of Daughters of the American Revolution, going back to Abraham Jones. Born in Washington D.C. in 1930, he grew up near one of the many horseshoe bends on Virginia's James River. His dad, an Army man, was always a Yankee to the Babers. “The ‘naturals’ down there were still like that,” smiled Tom, shaking his head.

His uncle Luther S. Baber’s general store is an image that stays with him in its scents and customs and a sign over the front door: “If we ain’t got it you don’t need it.” Tom remembers a big wheel of cheese. He’d always want to slice off a bit as he walked by. Uncle Luther was once asked by a customer to cut off a 40-cent wedge, and looking at the position of the knife said: “Well, how much could I get for a quarter?” Uncle Luther scowled: “For a quarter? You can smell the knife.”

Tom’s summers at that store at Centenary on Virginia’s James River gave birth to his early affection for our rivers. Wild river, teach me to flow, he sings, mellowing to life’s troubles.

Tom’s dad went off to fight in World War II, saying he was serving so Tom wouldn’t have to. He landed at Normandy and fought all the way to Nurenburg. But our world being what it is, young Tom as an air force corpsman was sent to Korea during that hard time, doing what he had to do.

Tom left Korea confused and saddened. When his returning troop ship docked on the West Coast he was ready to debark and resume his life, but an officer in a shiny silver helmet formed his mates into ranks at the rail, and, as they looked down, more men in shiny silver helmets emerged from the bowels of a lower deck carrying coffins. Tom didn’t count them, but he says there were at least 50, maybe 100.

He’s not sure why, because the meaning is so different, but sometimes when he performs his famous piece reciting rivers of the Chesapeake: Susque-hanna, Po-tomac and Wi-co-mico … he sees the coffins in his mind’s eye. Tom wrote of these rivers early in his love affair with the Bay, before, he says, the famous anti-war laments of the 1960s, like “Where have all the flowers gone?” Maybe his back-of-the-mind vision says something about the decline he’s seen in our rivers.

Shaped by the Chesapeake

The years after Korea, from the 1960s into the 1970s, shaped the Wisner personna, and through time’s mirror he looks back on then-director of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory Eugene Cronin as a mentor. Tom put together a wet-lab with Gene’s blessing, and a local teen worked with him building large shallow touch tanks for schoolkids, many years before they achieved today’s popularity in nature centers and aquaria. Wisner was growing, forming in this good time.

Tom Wisner has tried to reach kids since his early days, and he works in schools a lot. In a St. Mary’s County schoolyard, he created a huge map of the Chesapeake so school children could walk to the rivers and their headwaters or play roles as the living creatures that really own the Bay. That’s something Tom himself enjoys doing.

Tom bought an Eastern Shore crabber’s “barcat” skiff built by Capt. Leon Marsh over at Smith Island. By the time Geda came into his hands, she had seen better days. He thought to use her to take kids out sampling and oystering, an educational approach almost unheard of at the time. Insurance problems and management doubt made an end to Tom’s dream, which is today replicated aboard many of the surviving skipjacks and a few buy-boats he knew as working vessels in those days.

Somewhat reluctantly, Tom sold me Geda, and I ran her joyfully on the Patuxent until worms got the better of her traditional cross-planked hull. Tom Wisner’s words on watermen hold for me, as a sailor and biologist: Sailin’ is my pride, I bend my back to labor and ride out on the tide. It’s been my joy, since I’se a boy.

Geda’s on exhibit at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons today, and you can imagine her memories or just run a hand over her lovely lines any time you visit there. She’s of course not a vessel any more, just an exhibit, painted up with her seams dry and gaping.

Long ago Tom wrote a song about Calvert Countian Jake Sollers, to be part of an audiovisual kiosk at the museum. Jake would never go with him to hear the song and look at the exhibit. Tom thinks these old guys felt it despoiled the memories to trot them out for the public that way.

In that vein, he tells about waterman Wat Herbert, who came to talk with Wisner students down by the Potomac. Wat cried when he saw his old Blackistone Island dory on exhibit there. Just the sight of her on the hard immobile earth, never to sail again brought home Wat’s own mortality. Of course, he’s dead now.

Tom speaks eloquently about the working captains with whom he sailed in past decades — Alex Kellam and Sussanna ‘Susie’ Brinsfield among others — and they form a core within the stories, songs and anecdotes with which he enthralls audiences today. It was not that long ago when the working Chesapeake was a place of water which, in some senses, the land was there to serve and support. Tom speaks and sings of a life gone within the lifetime of many in his audiences. That’s how he appeals to many of us.

In “Dredgin’ is my Drudgery” he writes I plow the sea on Monday in reference to how skipjack oystermen viewed their work as a kind of agriculture. We push on Tuesday too. Wens’day is a sailing day, when I start missin’ you, recalls the special law that allows skipjacks to ‘push’ with power to help them overcome a tough market — and opens to the glory of working under sail that took men away from their families often and long.

Tom Wisner was part and parcel at the creation of now-retired Maryland Sen. Bernie Fowler’s Wade-Ins to celebrate past water clarity in the Bay and to audit its gains and declines over the last decade or so. He always attends the wade-ins to play, sing and greet old friends with the song he wrote for the occasion: Well we should do this yearly, on Bernie Fowler Day. Dress up fit to kill and wade out all the way. Tom, of course, always wades in and gets really wet.

A work in progress will take stories and legends shaped by Spearman Lancaster about the slave times at Swan Point Plantation and along the Potomac River. “Spearman would never let me record his stories,” Tom said. “He wanted me to listen to them, then tell them back to him, so he could see I’d gotten it right.”

Wisner’s latest CD, Made of Water: Songs of Chesapeake Riverlands, distills some of this life and the ethic he’s built over decades around the Bay. On the CD, Wisner’s joined by others, including vocalist Theresa Whitaker; Al Petteway, whose roots music is played around the region; and John Cronin, son of Tom’s late mentor, Eugene. Tom brings in a chorus, the kids from a Southern Maryland school.

Made of Water played better on second hearing for me. My cat listened with me, but on that winter Sunday morning, she was more interested in the bird and water sounds and startled by the thunder blended in by producers Tom Anderson and Jim Fox.

Listen to the disk more than once. Read the program notes included in the box, for they give context and depth to the performances. And remember Tom’s caution: “You’d better watch the songs you sing; they’re gonna make you who you are.”

All profits from the sale of this album benefit programs of the non-profit foundation Chestory, of which Tom Wisner is co-founder. Order from the Center for the Chesapeake Story, Box 1462 Solomons Island, MD 20688 • www.CHESTORY.org.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Dr. Kent Mountford, biologist and sailor, lives at Osborn Cove on the Patuxent. Formerly with the USEPA’s Bay Program, he now writes about environmental history of the Chesapeake, including a column for Bay Journal.

His most recent book is Closed Sea: Manasquan to the Mullica, a History of Barnegat Bay, which came out in May, 2002.