|

|

|

| Three Generations of Faunces: In America, Adam Pfanz’s descendants became Faunces: from left, George, John Sr., John Jr., young John Patrick and Michael. |

Ellis Island Records Go Electronic

Baltimore Begins Immigration Tours

by M.L. Faunce

When I began researching my family history just a few years back [“A Bay Weekly Primer: Setting Out on Your Roots Journey”: Vol. IX, No. 8, Feb. 24, 2000], I did it the old-fashioned way: plowing through dusty church records, reeling through miles of census data on microfilm at the National Archives, tramping through old cemeteries. Continuing the search last summer with a niece and nephew in tow, we rubbed tombstones with burnishing wax and butcher paper until the images of skulls and the names of the dearly departed gave these young souls the creeps.

But now, thanks to the latest technology and more than 12,000 volunteers from the Church of Jesus Christ Latter-Day Saints — the Mormons — the search for family history can be a lot less scary and more convenient. A mountain of immigration records has been computerized and made available on the web to cyber sleuths looking for their roots. The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation instigated the $15 million project.

The result is a wealth of information on the poignant history of more than 17 million mostly Europeans who entered the United States between 1892 and 1924 by way of Ellis Island. The information comes from the original ships’ manifests. Each handwritten ledger is a rich page of history: line by line, immigrants’ surnames, given names, genders, ages, marital status, and nationalities, including both town and country. Also recorded for each immigrant are the name of the ship, port of origin and arrival date.

You can visit the hugely popular site at www.ellisislandrecords.org and even purchase images of original ship manifests from commercial web sources that piggyback on official websites. Click on Passenger Search, and a whole new old world may open up. You can explore on-line resources and get tips on how to prepare for your search.

My own ancestors came to this country long before the teeming masses landed on Ellis Island in the late 1800s. But chances are some of your ancestors came through the country’s largest port at New York, for the six decades of arrivals there account for at least 40 percent of our population today.

Family historians, experienced or novice, who want to make the pilgrimage to New York can visit the American Family Immigration History Center on Ellis Island. Reserve a session on a computer work station or see documentaries on family history and the immigrant experience.

While you’re there, check out the view your ancestors saw entering New York Harbor after what was certainly a long and often nightmarish journey across the sea — with their journey only just beginning. Their first test in America was pass or fail: They were either admitted or deported, with a medical inspection and perceived ability to work determining who would get a landing card.

Baltimore’s Ellis Island

The second chapter in our nation’s immigration history was written right here in Chesapeake County, in Baltimore.

|

South Baltimore’s Locust Point. Baltimore’s Inner Harbor is at the left of the picture, the flag at Fort McHenry is near the center along with the Key Bridge (crossing Baltimore’s Outer Harbor in the distance), and the Locust Point Marine Terminal fills most of the right half.

photo courtesy of SouthBaltimore.com |

Germans, Polish, Irish, Italians and immigrants of many other nationalities stepped off the boat at Locust Point, signed up for work all along this busy shipping and industrial harbor, made their homes in waterfront neighborhoods, built churches and formed ethnic associations, like the German Society, that live on today. One of the hundreds of thousands was Gus Goldstein. The father of Maryland’s revered comptroller Louis Goldstein who died in 1998, Gus Goldstein signed on as a peddler and, with his wares and barely a word of English, traveled by steamboat to Calvert County, where he made his fortune.

Now, a man who hasn’t yet found time to trace his own immigrant roots, Ron Zimmerman, is working to make his city a destination for other seekers. Zimmerman, 74, a realtor and civic booster, has spent five years pitching an immigration museum for Baltimore.

The Immigration Gateway Interpretive Park at Tide Point hatched on a visit to the restored Ellis Island complex in New York. There Zimmerman and his wife learned that Baltimore — “not Boston or Philadelphia, but Baltimore,” he exclaims — was the second largest port of entry for immigrants to this country. Locust Point was called Ellis Island of Baltimore, he discovered.

Inspired, he set to work speaking to civic groups, business leaders and politicians about his project. He’s also collected correspondence, photos, memorabilia, even furniture, that would someday be part of a museum “so that people would realize what this country is made of,” he says.

Zimmerman is a man who knows how to get a thing done. One of nine children, he grew up in Southwest Baltimore, went to work at 14 and dug ditches for the city on his way to building his own successful real estate business in the city’s Federal Hill neighborhood.

|

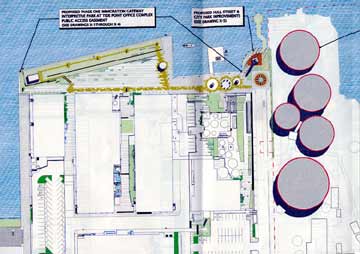

| Plans for the Immigration Gateway Interpretive Park at Tide Point, devised by Baltimore businessman Ron Zimmerman. The first stage opens this summer with a brick walkway for tours, then later with an orientation center and water-shuttle stop and shelter. An existing pump house will hold other interpretative features in an open-air setting on the waterfront at the Tide Point office complex in Locust Point. |

This summer, the first phase of Zimmerman’s dream will take shape. The Immigration Gateway Heritage Park will open, first with a brick walkway for walking tours, later with an orientation center and water-shuttle stop and shelter. An existing pump house will hold other interpretative features in an open-air setting on the waterfront place at the Tide Point office complex in Locust Point.

Walking tours, bearing the historical name Ellis Island in Baltimore, are being coordinated by The Preservation Society, which is developing grants to bring in the dollars to produce an interpretive, educational program describing the immigration settlement and experience. The first tours, beginning in July, will highlight the Polish and German émigrés and their living traditions.

Tide Point at Locust Point, near the Coast Guard Tower and at the foot of Hall Street, is a short water-taxi shuttle ride from the Inner Harbor and adjacent to Piers 8 and 9, the area where hundreds of thousands of immigrants — “a million people or better,” as Zimmerman puts it — arrived in the 19th and early 20th century.

At Tide Point, flags of the fatherlands and motherlands of generations of Marylanders will line the brick walkway. Next year, the annual naturalization ceremony swearing in new citizens of a new era of immigrants will be conducted here “facing the water,” Zimmerman says, where immigrants of past centuries first set foot.

Architectural plans are on the drawing board for the future Baltimore Immigration Museum. Funds are being raised and the site is under negotiation.

The museum isn’t a reality yet but, Zimmerman says, “all the seeds are planted; it will eventually happen.”

Starting July 13 and continuing on the third Saturday of every month, Ellis Island in Baltimore walking tours depart from Fells Point Visitors Center. To learn more: The Preservation Society, 410/675-6750 • www.preservationsociety.com.

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|