In Season: Persimmon

In Season: Persimmon

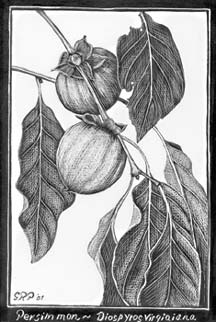

Story and scratchboard illustration by Gary Pendleton

If the fruit not be ripe it will draw a mans mouth with much torment.

— Capt. John Smith

The old captain’s boat may very well have been anchored in some local river when he described his first experience eating the fruit of the persimmon tree. Indeed, the unripe the fruit is powerfully astringent. The nasty orange flesh attacks the gums and palate. It feels as if cotton is growing from the most remote crevices of the mouth. Making matters worse, the irritating, puckering sensation lingers for a long time. It is very unpleasant, if not tormenting.

Over 300 years later, people are still discovering the wonders of persimmons. Just the other day my wife told me about a coworker who tried persimmon for the first time a few weeks ago. She was showing friends around the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary on the Patuxent. The novice taster expressed the same note of shock and surprise as John Smith.

Meanwhile, I was spending the morning at another wildlife sanctuary across the Bay. The place was rich with persimmon trees that were loaded with fruit. Some say that you must wait until after the first frost to find ripe persimmons, but that is not necessarily so. This was the last weekend of September but we enjoyed our fill of ripe fruit and could have eaten more. Over the years we have learned what to look for.

Persimmons are medium-size trees with bark that separates into blocky shapes like alligator hide. Their leaves are a glossy green, unlobed with a drip point at the end. As summer comes to an end, the pingpong-ball-size fruit ripens, changing from green to orange. The almost ripe fruit is as pretty as grocery store produce, but it is unsafe to eat until the flesh wrinkles and darkens and the pulp turns mushy. Your best bet is to look for the ugliest, most shriveled and wrinkled fruit.

I will even search the ground for fallen fruit. After brushing off the ants, I use my fingers to split open the fruit. Then I bite into the flesh that surrounds seeds. The ants seem to know what is ripe, but you can also try shaking the trunk to loosen ripe fruit. I take a small bite and wait half a minute for the puckering, which is a delayed reaction. When it seems safe, I proceed, taking care to avoid the thin membrane of the skin which never looses its astringent quality. It is not possible to eat a ripe persimmon daintily; sticky fingers are part of the game.

Persimmons range from the Atlantic west to East Texas and north to Ohio and Connecticut. It is in the same family as ebony. The wood is dark and very hard but has had limited commercial use because the trunks never exceed one-foot in diameter. However, the persimmon tree has made at least one important contribution to industry: The wood was used for loom shuttles, which are subject to so much stress that less durable woods can not take the constant use. Persimmons are an important food source for many species of wildlife, such as bob white quail, fox, squirrel and opossum.

The chance of sampling a not-quite-ripe persimmon is worth the risk because they are so good: they have a complex, sugary taste but are not too sweet. The scientific name, Diospyros, means fruit of Zeus.