Presidential Iconography

Abraham Lincoln, whose leadership the country celebrates on Presidents Day February 19, a week after his February 12 birthday, ranks as one of our best presidents. He won the Civil War, saved the Union, ended slavery and uttered some of the most eloquent words ever spoken by an American leader.

His immortal peroration from the Gettysburg Address on Nov. 19, 1863 — calling for a “new birth of freedom” and resolving that “government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth” — is vividly displayed on the Lincoln Memorial, inspiring millions who visit the site each year.

Lincoln also was a political innovator, a little-known fact.

One area in which he broke new ground was image-making, specifically the use of photography. As I point out in my new book, Ultimate Insiders: White House Photographers and How They Shape History, Lincoln was the first presidential candidate and the first president to construct an image for himself through photographs — a practice we now take for granted.

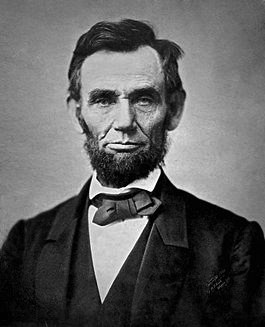

The photograph he had taken on February 27, 1860, was one of the most consequential developments of his political career and one of the most important images captured of any president.

Aiming to summarize his stand against slavery and explain his defense of the Union against secessionists, Lincoln planned to speak that day at New York’s Cooper Union, an academy in Manhattan. He decided to have his picture taken while there by the increasingly famous photographer Mathew Brady. He wanted the picture distributed nationwide to show that he was not simply a frontiersman — his image at the time — but also a man of vision and intelligence who was fully capable of serving in the nation’s highest office.

Lincoln, 51, arrived at Brady’s Bleecker Street studio a few hours before his big speech. He looked haggard and weary; he had dark rings under his eyes, and his rumpled clothes were too small for his six-foot-four frame.

Brady decided not to take a close-up but to pull the camera back — both to show Lincoln’s impressive stature and to make it more difficult to notice his imperfections. The photographer drew Lincoln’s collar up to hide his long neck and large Adam’s apple, and he smoothed his hair to further improve his look He also posed Lincoln in front of a false pillar, standing next to a table piled with books, with his left hand lightly touching the top volume, to indicate erudition.

Afterward, Brady did some primitive retouching, removing the dark patches under Lincoln’s eyes and blurring the deep lines in his face. (Lincoln was clean-shaven at the time. He grew his famous beard later, before he took office in March 1861.) Brady came up with the image of a candidate who appeared to be a strong, serious, determined leader — just what Lincoln wanted.

The photo turned out to be a brilliant idea that gave Lincoln the new, positive image he sought. “Its later proliferation and reproduction in prints, medallions, broadsides and banners said perhaps as much to create a ‘new’ Abraham Lincoln as did the Cooper Union address itself,” wrote historian Harold Holzer.

Lincoln won his party’s nomination three months later and was elected president six months after that. He credited the distribution of the photo along with texts of his Cooper Union speech as having won the election for him.

“Brady and the Cooper Institute made me president,” he said.

After he took office, Lincoln continued to have his photo taken with regularity; he posed for about 70 in all. This is a small number compared to the millions of photos taken of the president today. But Lincoln’s use of photography, an art still in its infancy during the 1860s, was very effective. His visage became “the most recognizable face in the country, but also the face of the nation,” writes author Richard Lowry, who adds: “He would present himself variously as commander-in-chief, as a citizen, as the leader of a democratic republic and as a ‘careworn’ face of the Union, embodying the harrowing grief and resolve he shared with those who elected him.”

Lincoln also had a good relationship with the photographers who took his picture, a camaraderie his most effective successors would realize was a big advantage in presidential image-making. That’s because the shooters, as they are called today, can easily make a president look bad or good, depending on how they compose their pictures and which ones they distribute.

Lincoln was clearly a particular fan of Mathew Brady’s. After the Civil War began in 1861, Brady wanted to take pictures of the battles and their aftermath and was concerned about being detained by Union troops. Brady walked from his Washington studio to the White House and told Lincoln of his worries. By this time, Lincoln had developed such trust in Brady that he wrote on a card, “Pass Brady. A. Lincoln.” It amounted to a special pass that led to Brady’s capturing some of the most compelling Civil War images.

One other photograph stands out. It was the image taken by Alexander Gardner, one of Brady’s associates, of Lincoln on February 5, 1865, a few weeks before he was murdered. As I write in Ultimate Insiders, Lincoln is shown as a frail, gaunt figure, staring into the distance, smiling faintly “as if a passing thought had brightened the moment.” But he is clearly “exhausted by the burdens of leading the Union through four years of carnage and suffering.”

Lincoln didn’t have his image softened or altered to make him look better. He wanted to show reality, how the burdens of the presidency had taken their toll. The result is one of the most poignant and moving images of any president, and a testament to Lincoln’s belief in the power of photography.

Kenneth T. Walsh is the chief White House correspondent for U.S. News & World Report. Ultimate Insiders is his eighth insider book on the presidency.